Russie – Wikipédia

Pays couvrant l'Europe de l'Est et l'Asie du Nord

Coordonnées: 60 ° N 90 ° E/60 ° N 90 ° E

|

Fédération Russe

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

![La Russie sur le globe avec des territoires non reconnus en vert clair.[a]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Russian_Federation_%28orthographic_projection%29_-_only_Crimea_disputed.svg/220px-Russian_Federation_%28orthographic_projection%29_-_only_Crimea_disputed.svg.png)

La Russie sur le globe avec des territoires non reconnus en vert clair.[a]

|

|

| Capitale

et la plus grande ville |

Moscou55 ° 45′N 37 ° 37′E/55,750 ° N 37,617 ° E |

| Langue officielle et langue nationale |

russe[2] |

| Reconnu langues nationales | Voir les langues de la Russie |

| Groupes ethniques | |

| Religion | |

| Démonyme (s) | russe |

| Gouvernement | République constitutionnelle fédérale semi-présidentielle |

| Vladimir Poutine | |

| Mikhail Mishustin | |

| Valentina Matviyenko | |

| Vyacheslav Volodin | |

| Vyacheslav Lebedev | |

| Corps législatif | Assemblée fédérale |

| Conseil de la fédération | |

| Douma d'État | |

| 862 | |

| 879 | |

| 1283 | |

| 16 janvier 1547 | |

| 2 novembre 1721 | |

| 15 mars 1917 | |

| 12 décembre 1991 | |

| 12 décembre 1993 | |

| 18 mars 2014 | |

| 4 juillet 2020 | |

|

• Le total |

17098246 km2 (6601,670 mi carrés)[5][b] (1er) |

|

• L'eau (%) |

13[7] (y compris les marais) |

|

• Estimation 2021 |

(9ème) |

|

• Densité |

8.4 / km2 (21.8 / mi carré) (181e) |

| PIB (PPP) | Estimation 2021 |

|

• Le total |

|

|

• Par habitant |

|

| PIB (nominal) | Estimation 2021 |

|

• Le total |

|

|

• Par habitant |

|

| Gini (2018) | moyen · 98e |

| HDI (2019) | très haut · 52e |

| Devise | Rouble russe (₽) (RUB) |

| Fuseau horaire | UTC + 2 à +12 |

| Côté conduite | droite |

| Indicatif d'appel | +7 |

| Code ISO 3166 | RU |

| TLD Internet | |

Russie (Russe: Россия, Rossiya, Prononciation russe: [rɐˈsʲijə]), ou la Fédération Russe,[c] est un pays couvrant l'Europe de l'Est et l'Asie du Nord. C'est le plus grand pays du monde, couvrant plus de 17 millions de kilomètres carrés (6,6×dix6 sq mi), et englobant plus d'un huitième de la superficie des terres habitées de la Terre. La Russie s'étend sur onze fuseaux horaires et a des frontières avec seize nations souveraines. Il a une population de 146,2 millions d'habitants; et est le pays le plus peuplé d'Europe et le neuvième pays le plus peuplé du monde. Moscou, la capitale, est la plus grande ville d'Europe, tandis que Saint-Pétersbourg est la deuxième plus grande ville et centre culturel du pays. Les Russes sont la plus grande nation slave et européenne; ils parlent le russe, la langue slave la plus parlée et la langue maternelle la plus parlée d'Europe.

Les Slaves de l'Est ont émergé comme un groupe reconnaissable en Europe entre le 3ème et le 8ème siècle après JC. L'état médiéval de Rus 'est né au 9ème siècle. En 988, il a adopté le christianisme orthodoxe de l'Empire byzantin, commençant la synthèse des cultures byzantine et slave qui ont défini la culture russe pour le prochain millénaire. Rus 's'est finalement désintégré jusqu'à ce qu'il soit finalement réunifié par le Grand-Duché de Moscou au 15ème siècle. Au 18ème siècle, la nation s'était considérablement développée par la conquête, l'annexion et l'exploration pour devenir l'Empire russe, le troisième plus grand empire de l'histoire. À la suite de la révolution russe, la SFSR russe est devenue le plus grand et le plus important constituant de l'Union soviétique, le premier État constitutionnellement socialiste du monde. L'Union soviétique a joué un rôle décisif dans la victoire des Alliés pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale et est devenue une superpuissance et une rivale des États-Unis pendant la guerre froide. L'ère soviétique a vu certaines des réalisations technologiques les plus importantes du XXe siècle, notamment le premier satellite artificiel au monde et le lancement du premier humain dans l'espace. À la suite de la dissolution de l'Union soviétique en 1991, la RSF russe s'est reconstituée en Fédération de Russie. Au lendemain de la crise constitutionnelle de 1993, une nouvelle constitution a été adoptée et la Russie est depuis gouvernée comme une république fédérale semi-présidentielle. Vladimir Poutine a dominé le système politique russe depuis 2000, et son gouvernement a été accusé d'autoritarisme, de nombreuses violations des droits de l'homme et de corruption.

La Russie est une grande puissance et est considérée comme une superpuissance potentielle. Il est classé très haut dans l'indice de développement humain, avec un système de santé universel et une éducation universitaire gratuite. L'économie de la Russie est la onzième du monde en termes de PIB nominal et la sixième en termes de PPA. C'est un État doté d'armes nucléaires reconnu, possédant le plus grand stock d'armes nucléaires au monde, avec la deuxième armée la plus puissante du monde et la quatrième dépense militaire la plus élevée. Les vastes ressources minérales et énergétiques de la Russie sont les plus importantes au monde et elle est l'un des principaux producteurs de pétrole et de gaz naturel au monde. Il est membre permanent du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies, membre du G20, de l'OCS, du Conseil de l'Europe, de l'APEC, de l'OSCE, de l'IIB et de l'OMC, ainsi que le principal membre de la CEI, l'OTSC. et l'EAEU. La Russie abrite également le neuvième plus grand nombre de sites du patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO.

Étymologie

Le nom Russie est dérivé de Rus ', un État médiéval peuplé principalement de Slaves de l'Est. Cependant, ce nom propre est devenu plus important dans l'histoire ultérieure, et le pays était généralement appelé par ses habitants "Русская земля" (Russkaya zemlya), qui peut être traduit par «terre russe» ou «terre de Rus». Afin de distinguer cet état des autres états qui en dérivent, il est noté Kievan Rus ' par l'historiographie moderne. Le nom Rus' lui-même vient du peuple Rus du début du Moyen Âge, des marchands et des guerriers suédois,[12][13] qui a déménagé de l'autre côté de la mer Baltique et a fondé un État centré sur Novgorod qui est devenu plus tard Kievan Rus '.

Une ancienne version latine du nom Rus 'était la Ruthénie, principalement appliquée aux régions occidentales et méridionales de Rus' qui étaient adjacentes à l'Europe catholique. Le nom actuel du pays, Россия (Rossiya), vient de la désignation grecque byzantine de la Rus ', Ρωσσία Rossía—Épelé Ρωσία (Rosía prononcé [roˈsia]) en grec moderne.[14]

La manière standard de désigner les citoyens de la Russie est «Russes» en anglais.[15] Il y a deux mots en russe qui sont communément traduits en anglais par «Russes» – l'un est «русские» (russkiye), qui se réfère le plus souvent aux Russes de souche – et l'autre est "россияне" (Rossiyane), qui fait référence aux citoyens russes, quelle que soit leur appartenance ethnique.[16]

Histoire

Histoire ancienne

L'un des premiers os humains modernes de plus de 40 000 ans a été trouvé dans le sud de la Russie, dans les villages de Kostyonki et Borshchyovo situés sur les rives du Don.[17][18]

Le pastoralisme nomade s'est développé dans la steppe pontique-caspienne à partir du Chalcolithique.[19] Des vestiges de ces civilisations steppiques ont été découverts dans des endroits comme Ipatovo,[19] Sintashta,[20] Arkaim,[21] et Pazyryk,[22] qui portent les plus anciennes traces connues de chevaux en guerre. Dans l'antiquité classique, la steppe pontique-caspienne était connue sous le nom de Scythie.[23]

À partir du 8ème siècle avant JC, les commerçants de la Grèce antique ont apporté leur civilisation aux emporiums commerciaux situés dans les villes russes de Tanais et Phanagoria.[24]

Aux 3ème et 4ème siècles après JC, le royaume gothique d'Oium existait dans le sud de la Russie, qui a ensuite été envahi par les Huns. Entre le IIIe et le VIe siècle après JC, le royaume du Bosporan, qui était un régime hellénistique qui succéda aux colonies grecques,[25] a également été submergé par les invasions nomades menées par des tribus guerrières telles que les Huns et les Avars eurasiens.[26] Les Khazars, d'origine turque, ont régné sur les steppes du bassin inférieur de la Volga entre la mer Caspienne et la mer Noire jusqu'au 10ème siècle.[27]

Les ancêtres des Russes modernes sont les tribus slaves, dont la maison d'origine serait, selon certains chercheurs, les zones boisées des marais de Pinsk, l'une des plus grandes zones humides d'Europe.[28] Les Slaves de l'Est ont progressivement installé la Russie occidentale en deux vagues: l'une se déplaçant de Kiev vers les actuels Souzdal et Mourom et une autre de Polotsk vers Novgorod et Rostov. À partir du 7ème siècle, les Slaves de l'Est constituaient la majeure partie de la population de la Russie occidentale,[29] et assimilé lentement mais pacifiquement les peuples finno-ougriens indigènes, y compris les Merya,[30] les Muromiens,[31] et le Meshchera.[32]

Kievan Rus '

La création des premiers États slaves de l'Est au IXe siècle a coïncidé avec l'arrivée de Varègues, les Vikings qui se sont aventurés le long des voies navigables s'étendant de la Baltique orientale aux mers Noire et Caspienne.[33] Selon le Chronique primaire, un Varègue du peuple Rus, nommé Rurik, fut élu souverain de Novgorod en 862. En 882, son successeur Oleg s'aventura vers le sud et conquit Kiev,[34] qui avait précédemment rendu hommage aux Khazars. Oleg, le fils de Rurik, Igor, et le fils d'Igor, Sviatoslav, ont par la suite soumis toutes les tribus slaves de l'Est locales à la domination de Kievan, détruit le Khazar Khaganate et lancé plusieurs expéditions militaires à Byzance et en Perse.

Aux Xe et XIe siècles, Kievan Rus 'est devenu l'un des États les plus grands et les plus prospères d'Europe.[35] Les règnes de Vladimir le Grand (980–1015) et de son fils Yaroslav le Sage (1019–1054) constituent l'âge d'or de Kiev, qui a vu l'acceptation du christianisme orthodoxe de Byzance et la création du premier code juridique écrit en slave oriental, les Russkaya Pravda.

Aux XIe et XIIe siècles, des incursions constantes de tribus nomades turques, telles que les Kipchaks et les Pechenegs, ont provoqué une migration massive des populations slaves orientales vers les régions plus sûres et fortement boisées du nord, en particulier vers la zone connue sous le nom de Zalesye;[36] ce qui a conduit à un mélange avec les tribus finnoises de la Volga.[37][38]

L'ère de la féodalité et de la décentralisation était venue, marquée par des combats incessants entre les membres de la dynastie Rurikid qui gouvernaient collectivement Kievan Rus. La domination de Kiev s'est affaiblie, au profit de Vladimir-Souzdal au nord-est, de la République de Novgorod au nord-ouest et de la Galice-Volhynie au sud-ouest.

Finalement, Kievan Rus s'est désintégré, le coup final étant l'invasion mongole de 1237–40,[39] qui a entraîné la destruction de Kiev,[40] et la mort d'environ la moitié de la population de Rus '.[41] Les envahisseurs, plus tard connus sous le nom de Tatars, ont formé l'État de la Horde d'or, qui a pillé les principautés russes et a gouverné les étendues sud et centrale de la Russie pendant plus de deux siècles.[42]

La Galice-Volhynie a finalement été assimilée par le Royaume de Pologne, tandis que la République de Novgorod et Vladimir-Souzdal dominée par les Mongols, deux régions à la périphérie de Kiev, ont jeté les bases de la nation russe moderne.[38] La République de Novgorod a échappé à l'occupation mongole et, avec Pskov, a conservé un certain degré d'autonomie à l'époque du joug mongol; ils ont été largement épargnés par les atrocités qui ont affecté le reste du pays. Dirigés par le prince Alexandre Nevsky, les Novgorodiens ont repoussé les envahisseurs suédois lors de la bataille de la Neva en 1240, ainsi que les croisés germaniques lors de la bataille de la glace en 1242.

Grand-Duché de Moscou

L'État le plus puissant à avoir finalement surgi après la destruction de Kievan Rus 'était le Grand-Duché de Moscou, qui faisait initialement partie de Vladimir-Souzdal. Bien que toujours sous le domaine des Mongols-Tatars et avec leur connivence, Moscou a commencé à affirmer son influence dans la Rus centrale au début du 14ème siècle, devenant progressivement la force dirigeante du processus de réunification et d'expansion des terres de la Rus. Russie.[43] Le dernier rival de Moscou, la République de Novgorod, prospéra en tant que principal centre du commerce des fourrures et port le plus à l'est de la Ligue hanséatique.

Les temps sont restés difficiles, avec de fréquents raids mongols-tatars. L'agriculture a souffert du début de la petite période glaciaire. Comme dans le reste de l'Europe, la peste était fréquente entre 1350 et 1490.[44] Cependant, en raison de la faible densité de population et d'une meilleure hygiène – pratique généralisée du banya, un bain de vapeur humide – le taux de mortalité par peste n'était pas aussi grave qu'en Europe occidentale,[45] et la population s'est rétablie en 1500.[44]

Dirigée par le prince Dmitri Donskoï de Moscou et aidée par l'Église orthodoxe russe, l'armée unie des principautés russes infligea une défaite importante aux Mongol-Tatars lors de la bataille de Koulikovo en 1380. Moscou absorba progressivement les principautés environnantes, y compris autrefois de puissants rivaux tels comme Tver et Novgorod.

Ivan III ("le Grand") a finalement jeté le contrôle de la Horde d'Or et a consolidé l'ensemble de la Rus centrale et du Nord sous la domination de Moscou. Il a également été le premier à remporter le titre de "Grand-Duc de toutes les Russies".[46] Après la chute de Constantinople en 1453, Moscou revendiqua la succession à l'héritage de l'Empire romain d'Orient. Ivan III a épousé Sophia Palaiologina, la nièce du dernier empereur byzantin Constantin XI, et a fait de l'aigle bicéphale byzantin son propre blason, et finalement de la Russie.

Tsardom de Russie

Dans le développement des idées de la Troisième Rome, le Grand-Duc Ivan IV (le "Terrible") a été officiellement couronné le premier Tsar de la Russie en 1547. Le Tsar promulgua un nouveau code de lois (Sudebnik de 1550), créa le premier organe représentatif féodal russe (Zemsky Sobor) et introduisit l'autogestion locale dans les régions rurales.[47][48]

Au cours de son long règne, Ivan le Terrible a presque doublé le déjà grand territoire russe en annexant les trois khanates tatars (parties de la Horde d'or désintégrée): Kazan et Astrakhan le long de la Volga et le Khanat sibérien dans le sud-ouest de la Sibérie. Ainsi, à la fin du XVIe siècle, la Russie s'est étendue à l'Asie et s'est transformée en un État transcontinental.[49]

Cependant, le Tsardom a été affaibli par la longue et infructueuse guerre de Livonie contre la coalition de la Pologne, de la Lituanie et de la Suède pour l'accès à la côte baltique et le commerce maritime.[50] Dans le même temps, les Tatars du khanat de Crimée, le seul successeur restant de la Horde d'Or, ont continué à attaquer le sud de la Russie.[51] Dans un effort pour restaurer les khanats de la Volga, la Crimée et ses alliés ottomans ont envahi la Russie centrale et ont même pu incendier des parties de Moscou en 1571.[52] Mais l'année suivante, la grande armée d'invasion a été complètement vaincue par les Russes lors de la bataille de Molodi, éliminant à jamais la menace d'une expansion ottomane-criméenne en Russie. Les raids d'esclaves de Crimée, cependant, n'ont cessé jusqu'à la fin du XVIIe siècle, bien que la construction de nouvelles lignes de fortification à travers le sud de la Russie, telles que la ligne des Grands Abatis, ait constamment réduit la zone accessible aux incursions.[53]

La mort des fils d'Ivan a marqué la fin de l'ancienne dynastie Rurik en 1598 et, en combinaison avec la famine de 1601–03, a conduit à une guerre civile, au règne des prétendants et à une intervention étrangère pendant le temps des troubles au début du 17e siècle.[54] Le Commonwealth polono-lituanien occupait des parties de la Russie, y compris Moscou. En 1612, les Polonais ont été contraints de battre en retraite par le corps des volontaires russes, dirigé par deux héros nationaux, le marchand Kuzma Minin et le prince Dmitri Pojarski. La dynastie des Romanov accéda au trône en 1613 par décision de Zemsky Sobor, et le pays commença sa sortie progressive de la crise.

La Russie a poursuivi sa croissance territoriale au XVIIe siècle, qui était l'âge des cosaques. En 1648, les paysans d'Ukraine rejoignirent les cosaques zaporozhiens en rébellion contre la Pologne-Lituanie pendant le soulèvement de Khmelnytsky en réaction à l'oppression sociale et religieuse qu'ils avaient subie sous la domination polonaise. En 1654, le dirigeant ukrainien, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, proposa de placer l'Ukraine sous la protection du tsar russe Aleksey I. L'acceptation de cette offre par Aleksey I. Aleksey conduisit à une autre guerre russo-polonaise. Enfin, l'Ukraine a été divisée le long du Dniepr, laissant la partie occidentale, rive droite de l'Ukraine, sous la domination polonaise et la partie orientale (Ukraine sur la rive gauche et Kiev) sous la domination russe. Plus tard, en 1670–71, les cosaques de Don dirigés par Stenka Razin ont lancé un soulèvement majeur dans la région de la Volga, mais les troupes du tsar ont réussi à vaincre les rebelles.[55]

À l'est, l'exploration et la colonisation rapides par la Russie des immenses territoires de la Sibérie ont été menées principalement par les cosaques à la recherche de fourrures et d'ivoire de valeur. Les explorateurs russes ont poussé vers l'est principalement le long des routes de la rivière sibérienne, et au milieu du 17e siècle, il y avait des colonies russes en Sibérie orientale, sur la péninsule de Tchouktche, le long du fleuve Amour et sur la côte Pacifique. En 1648, Fedot Popov et Semyon Dezhnyov, deux explorateurs russes, découvrent le détroit de Béring; ce qui a conduit les Russes à devenir les premiers Européens à naviguer vers l'Amérique du Nord.[56]

Russie impériale

Sous Pierre le Grand, la Russie a été proclamée Empire en 1721 et est devenue une puissance mondiale. Au pouvoir de 1682 à 1725, Peter a vaincu la Suède dans la Grande Guerre du Nord, la forçant à céder la Carélie occidentale et l'Ingrie (deux régions perdues par la Russie au temps des troubles),[57] ainsi que l'Estland et Livland, garantissant l'accès de la Russie au commerce maritime et maritime.[58] Sur la mer Baltique, Peter a fondé une nouvelle capitale appelée Saint-Pétersbourg. Plus tard, ses réformes ont apporté des influences culturelles considérables d'Europe occidentale à la Russie.

Le règne d'Elizabeth, la fille de Pierre Ier, en 1741-1762, a vu la Russie participer à la guerre de Sept Ans (1756-17563). Pendant ce conflit, la Russie a annexé la Prusse orientale pendant un certain temps et a même pris Berlin. Cependant, à la mort d'Elisabeth, toutes ces conquêtes ont été rendues au royaume de Prusse par le pro-prussien Pierre III de Russie.

Catherine II ("la Grande"), qui a régné en 1762-1796, a présidé le siècle des Lumières russes. Elle a étendu le contrôle politique russe sur le Commonwealth polono-lituanien et a incorporé la plupart de ses territoires à la Russie pendant les partitions de la Pologne, poussant la frontière russe vers l'ouest en Europe centrale. Dans le sud, après les guerres russo-turques réussies contre la Turquie ottomane, Catherine a avancé la frontière de la Russie jusqu'à la mer Noire, battant le khanat de Crimée. À la suite des victoires sur l'Iran Qajar à travers les guerres russo-perses, dans la première moitié du 19e siècle, la Russie a également réalisé des gains territoriaux importants en Transcaucasie et dans le Caucase du Nord.[59][60] Le successeur de Catherine, son fils Paul, était instable et se concentrait principalement sur les questions domestiques. Après son court règne, la stratégie de Catherine s'est poursuivie avec le fait qu'Alexandre Ier (1801-1825) arrachait la Finlande au royaume affaibli de Suède en 1809 et la Bessarabie aux Ottomans en 1812. Dans le même temps, les Russes devinrent les premiers Européens à coloniser l'Alaska. et fondé des colonies en Californie, comme Fort Ross.

En 1803-1806, la première circumnavigation russe a été faite, suivie plus tard par d'autres voyages d'exploration en mer russes notables. En 1820, une expédition russe découvre le continent de l'Antarctique.

Dans des alliances avec divers autres pays européens, la Russie s'est battue contre la France de Napoléon. L'invasion française de la Russie à l'apogée de la puissance de Napoléon en 1812 a atteint Moscou, mais a finalement échoué lamentablement car la résistance obstinée en combinaison avec l'hiver russe extrêmement froid a conduit à une défaite désastreuse des envahisseurs, dans laquelle plus de 95% de la pan- La Grande Armée européenne a péri.[61] Dirigée par Mikhail Kutuzov et Barclay de Tolly, l'armée russe a évincé Napoléon du pays et a conduit à travers l'Europe dans la guerre de la Sixième Coalition, entrant finalement à Paris. Alexandre Ier a dirigé la délégation russe au Congrès de Vienne qui a défini la carte de l'Europe post-napoléonienne.

Les officiers des guerres napoléoniennes ont ramené avec eux des idées de libéralisme en Russie et ont tenté de restreindre les pouvoirs du tsar lors de la révolte avortée des décembristes de 1825. À la fin du règne conservateur de Nicolas Ier (1825-1855), une période zénithale de La puissance et l'influence de la Russie en Europe ont été perturbées par la défaite lors de la guerre de Crimée. Entre 1847 et 1851, environ un million de personnes sont mortes du choléra asiatique.[62]

Le successeur de Nicolas, Alexandre II (1855-1881), a apporté des changements importants dans le pays, y compris la réforme d'émancipation de 1861. Ces Grandes réformes a stimulé l'industrialisation et modernisé l'armée russe, qui avait réussi à libérer la Bulgarie de la domination ottomane lors de la guerre russo-turque de 1877-1878.

La fin du 19e siècle a vu la montée de divers mouvements socialistes en Russie. Alexandre II a été tué en 1881 par des terroristes révolutionnaires et le règne de son fils

Alexandre III (1881–1894) était moins libéral mais plus pacifique. Le dernier empereur russe, Nicolas II (1894–1917), fut incapable d'empêcher les événements de la révolution russe de 1905, déclenchés par l'échec de la guerre russo-japonaise et l'incident de démonstration connu sous le nom de Bloody Sunday. Le soulèvement a été réprimé, mais le gouvernement a été contraint de concéder des réformes majeures (Constitution russe de 1906), notamment l'octroi des libertés d'expression et de réunion, la légalisation des partis politiques et la création d'un organe législatif élu, la Douma d'État de l'Empire russe. La réforme agraire de Stolypin a conduit à une migration et une installation paysannes massives en Sibérie. Plus de quatre millions de colons sont arrivés dans cette région entre 1906 et 1914.[63]

Révolution de février et République russe

En 1914, la Russie est entrée dans la Première Guerre mondiale en réponse à la déclaration de guerre de l'Autriche-Hongrie à l'allié de la Russie, la Serbie, et a combattu sur plusieurs fronts tout en étant isolée de ses alliés de la Triple Entente. En 1916, l'offensive Brusilov de l'armée russe détruisit presque complètement l'armée de l'Autriche-Hongrie. Cependant, la méfiance déjà existante du public à l'égard du régime a été aggravée par la hausse des coûts de la guerre, le nombre élevé de victimes et les rumeurs de corruption et de trahison. Tout cela a formé le climat de la Révolution russe de 1917, réalisée en deux actes majeurs.

La révolution de février a forcé Nicolas II à abdiquer; lui et sa famille ont été emprisonnés puis exécutés à Ekaterinbourg pendant la guerre civile russe. La monarchie a été remplacée par une coalition fragile de partis politiques qui s'est déclarée gouvernement provisoire. Le 1er septembre (14) 1917, par décret du gouvernement provisoire, la République de Russie est proclamée.[64] Le 6 janvier (19) 1918, l'Assemblée constituante russe a déclaré la Russie république fédérale démocratique (ratifiant ainsi la décision du gouvernement provisoire). Le lendemain, l'Assemblée constituante a été dissoute par le Comité exécutif central panrusse.

Guerre civile russe

Un autre établissement socialiste coexistait, le Soviet de Petrograd, exerçant le pouvoir par le biais de conseils démocratiquement élus d'ouvriers et de paysans, appelés Soviétiques. Le règne des nouvelles autorités n'a fait qu'aggraver la crise dans le pays au lieu de la résoudre. Finalement, la Révolution d'octobre, dirigée par le leader bolchevique Vladimir Lénine, a renversé le gouvernement provisoire et donné le plein pouvoir de gouvernement aux Soviétiques, conduisant à la création du premier État socialiste du monde.

Après la Révolution d'octobre, la guerre civile russe a éclaté entre le mouvement anti-communiste blanc et le nouveau régime soviétique avec son armée rouge. La Russie bolcheviste a perdu ses territoires ukrainiens, polonais, baltes et finlandais en signant le traité de Brest-Litovsk qui a conclu les hostilités avec les puissances centrales de la Première Guerre mondiale.Les puissances alliées ont lancé une intervention militaire infructueuse en soutien aux forces anticommunistes. Dans l'intervalle, les bolcheviks et les mouvements blancs ont mené des campagnes de déportations et d'exécutions l'un contre l'autre, connues respectivement sous le nom de Terreur rouge et Terreur blanche. À la fin de la guerre civile, l'économie et les infrastructures de la Russie ont été gravement endommagées. Il y a eu entre 7 et 12 millions de victimes pendant la guerre, principalement des civils.[65] Des millions sont devenus des émigrés blancs,[66] et la famine russe de 1921–22 a fait jusqu'à cinq millions de victimes.[67]

Union soviétique

Le 30 décembre 1922, Lénine et ses collaborateurs formèrent l'Union soviétique, en fusionnant la SFSR russe avec la SFSR ukrainienne, biélorusse et transcaucasienne. Sur les 15 républiques de l'Union soviétique, la plus grande en taille et en population était la RSF russe, qui a dominé l'Union pendant toute son histoire sur les plans politique, culturel et économique.

Après la mort de Lénine en 1924, une troïka a été désignée pour en prendre la charge. Finalement, Joseph Staline, le secrétaire général du Parti communiste, a réussi à supprimer toutes les factions d'opposition et à consolider le pouvoir entre ses mains pour devenir le dictateur du pays dans les années 1930. Léon Trotsky, le principal partisan de la révolution mondiale, a été exilé de l'Union soviétique en 1929, et l'idée de Staline du socialisme dans un seul pays est devenue la ligne officielle. La lutte interne continue dans le parti bolchevique a abouti à la Grande Purge, une période de répressions massives en 1937–38, au cours de laquelle des centaines de milliers de personnes ont été exécutées, y compris des membres originaux du parti et des chefs militaires forcés d'avouer des complots inexistants.[68]

Sous la direction de Staline, le gouvernement a lancé une économie dirigée, l'industrialisation du pays en grande partie rural et la collectivisation de son agriculture. Pendant cette période de changement économique et social rapide, des millions de personnes ont été envoyées dans des camps de travail pénitentiaires,[69] y compris de nombreux condamnés politiques pour leur opposition présumée ou réelle au régime de Staline; des millions ont été déportés et exilés vers des régions reculées de l'Union soviétique.[69] La désorganisation transitoire de l'agriculture du pays, combinée aux politiques étatiques sévères et à une sécheresse, a conduit à la famine soviétique de 1932-1933,[70] qui a tué entre 2 et 3 millions de personnes dans la RSFS russe.[71] L'Union soviétique a procédé en peu de temps à la transformation coûteuse d'une économie largement agraire en une grande puissance industrielle.

La Seconde Guerre mondiale

Le 22 juin 1941, l'Allemagne nazie a rompu son traité de non-agression; et envahi l'Union soviétique mal préparée avec la force d'invasion la plus grande et la plus puissante de l'histoire de l'humanité,[72] ouverture du plus grand théâtre de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Le plan nazi contre la faim prévoyait «l'extinction de l'industrie ainsi que d'une grande partie de la population».[73] Près de 3 millions de prisonniers de guerre soviétiques en captivité allemande ont été assassinés en seulement huit mois de 1941 à 1942.[74] Bien que la Wehrmacht ait eu un succès précoce considérable, son attaque a été stoppée lors de la bataille de Moscou. Par la suite, les Allemands ont d'abord subi des défaites majeures lors de la bataille de Stalingrad à l'hiver 1942–43,[75] puis lors de la bataille de Koursk à l'été 1943. Un autre échec allemand fut le siège de Leningrad, au cours duquel la ville fut totalement bloquée sur terre entre 1941 et 1944 par les forces allemandes et finlandaises, et souffrit de la famine et de plus d'un million de morts. , mais ne s'est jamais rendu.[76] Sous l'administration de Staline et sous la direction de commandants tels que Georgy Joukov et Konstantin Rokossovsky, les forces soviétiques ont traversé l'Europe centrale et orientale en 1944-1945 et ont capturé Berlin en mai 1945. En août 1945, l'armée soviétique a chassé les Japonais du Mandchoukouo et de la Corée du Nord. , contribuant à la victoire alliée sur le Japon.

La période 1941–45 de la Seconde Guerre mondiale est connue en Russie sous le nom de «Grande guerre patriotique». L'Union soviétique ainsi que les États-Unis, le Royaume-Uni et la Chine ont été considérés comme les quatre grands des puissances alliées pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale,[77] et est devenu plus tard les quatre policiers qui ont été la fondation du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies.[78] Au cours de cette guerre, qui comprenait bon nombre des opérations de combat les plus meurtrières de l'histoire de l'humanité, les morts civils et militaires soviétiques étaient d'environ 27 millions, soit environ un tiers de toutes les victimes de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. La perte démographique totale des citoyens soviétiques était encore plus grande.[79] L'économie et les infrastructures soviétiques ont subi des ravages massifs qui ont provoqué la famine soviétique de 1946–47. Néanmoins, l'Union soviétique est devenue une superpuissance mondiale dans la foulée.

Guerre froide

After World War II, Eastern and Central Europe, including East Germany and eastern parts of Austria were occupied by Red Army according to the Potsdam Conference. Dependent socialist governments were installed in the Eastern Bloc satellite states. After becoming the world's second nuclear power, the Soviet Union established the Warsaw Pact alliance and entered into a struggle for global dominance, known as the Cold War, with the rivaling United States and NATO.

After Stalin's death and a short period of collective rule, the new leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and launched the policy of de-Stalinisation. The penal labor system was reformed and many prisoners were released and rehabilitated (many of them posthumously).[80] The general easement of repressive policies became known later as the Khrushchev Thaw. At the same time, tensions with the United States heightened when the two rivals clashed over the deployment of the United States Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Soviet missiles in Cuba.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, thus starting the Space Age. Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth, aboard the Vostok 1 manned spacecraft on 12 April 1961. Following the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964, another period of collective rule ensued, until Leonid Brezhnev became the leader. The era of the 1970s and the early 1980s was later designated as the Era of Stagnation, a period when economic growth slowed and social policies became static. The 1965 Kosygin reform aimed for partial decentralisation of the Soviet economy and shifted the emphasis from heavy industry and weapons to light industry and consumer goods but was stifled by the conservative Communist leadership. In 1979, after a Communist-led revolution in Afghanistan, Soviet forces invaded the country. The occupation drained economic resources and dragged on without achieving meaningful political results. Ultimately, the Soviet Army was withdrawn from Afghanistan in 1989 due to international opposition, persistent anti-Soviet guerrilla warfare, and a lack of support by Soviet citizens.

From 1985 onwards, the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who sought to enact liberal reforms in the Soviet system, introduced the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to end the period of economic stagnation and to democratise the government. This, however, led to the rise of strong nationalist and separatist movements. Prior to 1991, the Soviet economy was the world's second-largest,[81] but during its final years, it was afflicted by shortages of goods in grocery stores, huge budget deficits, and explosive growth in the money supply leading to inflation.[82]

By 1991, economic and political turmoil began to boil over as the Baltic states chose to secede from the Soviet Union. On 17 March, a referendum was held, in which the vast majority of participating citizens voted in favour of changing the Soviet Union into a renewed federation. In August 1991, a coup d'état attempt by members of Gorbachev's government, directed against Gorbachev and aimed at preserving the Soviet Union, instead led to the end of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. On 25 December 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved, and along with Russia, fourteen other post-Soviet states emerged.

Post-Soviet Russia (1991–present)

In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin became the first directly elected president in Russian history when he was elected President of the Russian SFSR, which became the independent Russian Federation in December of that year. The economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union led to a deep and prolonged depression, characterised by a 50% decline in both GDP and industrial output between 1990 and 1995, although some of the recorded declines may have been a result of an upward bias in Soviet-era economic data.[83][84] During and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, wide-ranging reforms including privatisation and market and trade liberalisation were undertaken,[83] including radical changes along the lines of "shock therapy" as recommended by the United States and the International Monetary Fund.[85]

The privatisation largely shifted control of enterprises from state agencies to individuals with inside connections in the government. Many of the newly rich moved billions in cash and assets outside of the country in an enormous capital flight.[86] The depression of the economy led to the collapse of social services; the birth rate plummeted while the death rate skyrocketed.[87] Millions plunged into poverty, from a level of 1.5% in the late Soviet era to 39–49% by mid-1993.[88] The 1990s saw extreme corruption and lawlessness, the rise of criminal gangs and violent crime.[89]

In late 1993, tensions between Yeltsin and the Russian parliament culminated in a constitutional crisis which ended after military force. During the crisis, Yeltsin was backed by Western governments, and over 100 people were killed. In December, a referendum was held and approved, which introduced a new constitution, giving the president enormous powers.

The 1990s were plagued by armed conflicts in the North Caucasus, both local ethnic skirmishes and separatist Islamist insurrections. From the time Chechen separatists declared independence in the early 1990s, an intermittent guerrilla war has been fought between the rebel groups and the Russian Armed Forces. Terrorist attacks against civilians carried out by separatists, most notably the Moscow theater hostage crisis and Beslan school siege, caused hundreds of deaths.

Russia took up the responsibility for settling the Soviet Union's external debts, even though its population made up just half of it at the time of its dissolution.[89] In 1992, most consumer price controls were eliminated, causing extreme inflation and significantly devaluing the Ruble.[90] With a devalued ruble, the Russian government struggled to pay back its debts to internal debtors, as well as international institutions like the International Monetary Fund.[91] Despite significant attempts at economic restructuring, Russia's debt outpaced GDP growth. High budget deficits coupled with increasing capital flight and inability to pay back debts,[92] caused the 1998 Russian financial crisis,[90] and resulted in a further GDP decline.[82]

Putin era

On 31 December 1999, President Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned, handing the post to the recently appointed Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin. Yeltsin left office widely unpopular, with an approval rating as low as 2% by some estimates.[93] Putin then won the 2000 presidential election and suppressed the Chechen insurgency. As a result of high oil prices, a rise in foreign investment, and prudent economic and fiscal policies, the Russian economy grew for eight straight years; improving the standard of living, and increasing Russia's influence on the world stage.[94] Putin went on to win a second presidential term in 2004. Following the global economic crisis of 2008 and a subsequent drop in oil prices, Russia's economy stagnated in 2009. And from 2010 to 2013, Russia enjoyed high economic growth; until falling oil prices coupled with international sanctions after the annexation of Crimea and the Russo-Ukrainian War led to the economy shrinking in 2015, though it rebounded in 2016, and the recession officially ended.[95] Many reforms made during the Putin presidency have been criticised as authoritarian,[96] while Putin's leadership over the return of order, stability, and prosperity has won him widespread admiration in Russia.[97]

On 2 March 2008, Dmitry Medvedev was elected President of Russia while Putin became Prime Minister. The constitution prohibited Putin from serving a third consecutive presidential term. Putin returned to the presidency following the 2012 presidential elections, and Medvedev was appointed Prime Minister. This quick succession in leadership change was coined "tandemocracy" by outside media. Some critics claimed that the leadership change was superficial, and that Putin remained as the decision making force in the Russian government, while other political analysts viewed it as truly tandem.[98][99] Alleged fraud in the 2011 parliamentary elections and Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 sparked mass protests, which lasted until 2013.

In 2014, after President Viktor Yanukovych of Ukraine fled as a result of a revolution, Putin requested and received authorisation from the Russian parliament to deploy Russian troops to Ukraine, leading to the takeover of Crimea.[100] Following a Crimean referendum in which separation was favoured by a large majority of voters,[101] the Russian leadership announced the accession of Crimea into the Russian Federation, though this and the referendum that preceded it were not accepted internationally.[102] The annexation of Crimea led to sanctions by Western countries, in which the Russian government responded with its own against a number of countries.[103][104]

In September 2015, Russia started military intervention in the Syrian Civil War in support of the Syrian government, consisting of airstrikes against militant groups of the Islamic State, al-Nusra Front (al-Qaeda in the Levant), the Army of Conquest and other rebel groups.

During March 2017 and October 2018, the country saw mass protests, which were primarily concerned with suppressing corruption in the Russian government and abandoning the planned retirement age hike. Amidst of the protests, during March 2018, Putin was elected for a fourth presidential term overall.

During July to September 2019, protests were held in Moscow, which was caused by the rejection to allow the independent candidates to participate in the 2019 Moscow City Duma election. In January 2020, substantial amendments to the constitution were proposed and took effect in July following a national vote, allowing Putin to run for two more six-year presidential terms after his current term ends.[105] In April 2021, Putin signed the constitutional change into law.[106] Since July 2020, protests have been continuing in Khabarovsk Krai and other regions of Siberia, which was caused by the arrest of Sergei Furgal. In January 2021, widespread protests began across the country, due to the arrest of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and have been ongoing.

Politique

According to the Constitution of Russia, the country is an asymmetric federation and semi-presidential republic, wherein the President is the head of state,[107] and the Prime Minister is the head of government. The Russian Federation is fundamentally structured as a multi-party representative democracy, with the federal government composed of three branches:[108]

- Legislative: The bicameral Federal Assembly of Russia, made up of the 450-member State Duma and the 170-member Federation Council, adopts federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse and the power of impeachment of the President.

- Executive: The President is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, can veto legislative bills before they become law, and appoints the Government of Russia (Cabinet) and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies.

- Judiciary: The Constitutional Court, Supreme Court and lower federal courts, whose judges are appointed by the Federation Council on the recommendation of the President, interpret laws and can overturn laws they deem unconstitutional.

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term (eligible for a second term, but not for a third consecutive term).[109] Ministries of the government are composed of the Premier and his deputies, ministers, and selected other individuals; all are appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Prime Minister (whereas the appointment of the latter requires the consent of the State Duma).

Political divisions

According to the constitution, Russia comprises 85 federal subjects.[d] In 1993, when the new constitution was adopted, there were 89 federal subjects listed, but later some of them were merged. These subjects have equal representation—two delegates each—in the Federation Council.[110] However, they differ in the degree of autonomy they enjoy.

- 46 oblasts (provinces): most common type of federal subjects, with locally elected governor and legislature.[111]

- 22 republics: nominally autonomous; each is tasked with drafting its own constitution, direct-elected,[111] head of republic,[112] or a similar post, and parliament. Republics are allowed to establish their own official language alongside Russian but are represented by the federal government in international affairs. Republics are meant to be home to specific ethnic minorities.

- 9 krais (territories): essentially the same as oblasts. The "territory" designation is historic, originally given to frontier regions and later also to the administrative divisions that comprised autonomous okrugs or autonomous oblasts.

- 4 autonomous okrugs (autonomous districts): originally autonomous entities within oblasts and krais created for ethnic minorities, their status was elevated to that of federal subjects in the 1990s. With the exception of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, all autonomous okrugs are still administratively subordinated to a krai or an oblast of which they are a part.

- 1 autonomous oblast (the Jewish Autonomous Oblast): historically, autonomous oblasts were administrative units subordinated to krais. In 1990, all of them except for the Jewish Autonomous Oblast were elevated in status to that of a republic.

- 3 federal cities (Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Sevastopol): major cities that function as separate regions.

- Federal districts

Federal subjects are grouped into eight federal districts, each administered by an envoy appointed by the President of Russia.[113] Unlike the federal subjects, the federal districts are not a subnational level of government but are a level of administration of the federal government.

Foreign relations

As of 2019[update], Russia has the fifth-largest diplomatic network in the world; maintaining diplomatic relations with 190 United Nations member states, two partially-recognized states, and three United Nations observer states; with 144 embassies.[114] It is considered a potential superpower; and is one of five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Russia is a member of the G20, the Council of Europe, the OSCE, and the APEC, and takes a leading role in organisations such as the CIS, the EAEU, the CSTO, the SCO, and BRICS.

Russia maintains positive relations with other countries of SCO,[115] EAEU,[116] and BRICS,[117] especially with neighbouring Belarus, which is in the Union State, a supranational confederation of the latter with Russia.[118] Serbia has been a historically close ally of Russia since centuries, as both countries share a strong mutual cultural, ethnic, and religious affinity.[119] In the 21st century, Sino-Russian relations have significantly strengthened bilaterally and economically—the Treaty of Friendship, and the construction of the ESPO oil pipeline and the Power of Siberia gas pipeline formed a special relationship between the two.[120] India is the largest customer of Russian military equipment, and the two countries share a historically strong strategic and diplomatic relationship.[121]

Militaire

The Russian Armed Forces are divided into the Ground Forces, Navy, and Aerospace Forces. There are also two independent arms of service: Strategic Missile Troops and the Airborne Troops. As of 2019[update], the military had almost one million active-duty personnel, the fourth-largest in the world.[122] Additionally, there are over 2.5 million reservists, with the total number of reserve troops possibly being as high as 20 million.[123] It is mandatory for all male citizens aged 18–27 to be drafted for a year of service in Armed Forces.[124]

Russia boasts the world's second-most powerful military,[125] and is among the five recognised nuclear-weapons states, with the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons in the world. More than half of the world's 14,000 nuclear weapons are owned by Russia.[126] The country possesses the second-largest fleet of ballistic missile submarines,[127] and is one of the only three states operating strategic bombers,[128] with the world's most powerful ground force,[129] the second-most powerful air force,[130] and the third-most powerful navy fleet.[131] Russia has the fourth-highest military expenditure in the world, spending $65.1 billion in 2019.[132] It has a large and fully indigenous arms industry, producing most of its own military equipment. In 2019, Russia was the world's third-biggest exporter of arms, behind only the United States and China.[133]

Human rights and corruption

Russia's human rights management has been increasingly criticised by leading democracy and human rights watchdogs. In particular, such organisations as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch consider Russia to have not enough democratic attributes and to allow few political rights and civil liberties to its citizens.[134][135] Since 2004, Freedom House has ranked Russia as "not free" in its Freedom in the World survey.[136] Since 2011, the Economist Intelligence Unit has ranked Russia as an "authoritarian regime" in its Democracy Index, ranking it 124th out of 167 countries for 2020.[137] Russia was ranked 149th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index for 2020.[138]

Russia was the lowest rated European country in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2020; ranking 129th out of 180 countries.[139] Corruption is perceived as a significant problem in Russia,[140] impacting various aspects of life, including the economy,[141] business,[142] public administration,[143][144] law enforcement,[145] healthcare,[146] and education.[147] The phenomenon of corruption is strongly established in the historical model of public governance, and attributed to general weakness of rule of law in Russia.[140]

Geography

Russia is the largest country in the world, covering a total area of 17,075,200 square kilometres (6,592,800 sq mi). It is a transcontinental country spanning much of the landmass of Eurasia, stretching vastly over both Europe and Asia. Russia has the fourth-longest coastline in the world, at 37,653 km (23,396 mi),[e] and lies between latitudes 41° and 82° N, and longitudes 19° E and 169° W. It is larger, by size, than three continents: Oceania, Europe, and Antarctica, and is slightly smaller than the dwarf planet of Pluto by surface area.[148]

The two most widely separated points in Russia are about 8,000 km (4,971 mi) apart along a geodesic line.[f] Mountain ranges are found along the southern regions, which shares a part of the Caucasus Mountains (containing Mount Elbrus; which at 5,642 m (18,510 ft) is the highest and most prominent peak in both Russia and Europe), the Altai Mountains in Siberia, and the Verkhoyansk Range or the volcanoes of Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East. The Ural Mountains, running north to south through the country's west, are rich in mineral resources, and divide Europe and Asia.

The Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Barents Sea, White Sea, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea, East Siberian Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Sea, Sea of Azov, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Sea of Japan are linked to Russia via the Arctic, Pacific, and the Atlantic. Russia's major islands and archipelagos include Novaya Zemlya, the Franz Josef Land, the Severnaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island, the Kuril Islands, and Sakhalin. The Diomede Islands are just 3 km (1.9 mi) apart, and Kunashir Island is about 20 km (12.4 mi) from Hokkaido, Japan.

Russia has one of the world's largest surface water resources; with its lakes containing approximately one-quarter of the world's liquid fresh water.[149] The largest and most prominent of Russia's bodies of fresh water is Lake Baikal, the world's deepest, purest, oldest and most capacious fresh water lake;[150] which alone contains over one-fifth of the world's fresh surface water.[149] Other major lakes include Ladoga and Onega, two of the largest lakes in Europe. Russia is second only to Brazil in volume of the total renewable water resources. Out of the country's 100,000 rivers,[151] the Volga is the most famous—it is the longest river in Europe.[124] The Siberian rivers of Ob, Yenisey, Lena and Amur are among the world's longest rivers.

Climate

The enormous size of Russia and the remoteness of many areas from the sea result in the dominance of the humid continental climate, which is prevalent in all parts of the country except for the tundra and the extreme southwest. Mountains in the south obstruct the flow of warm air masses from the Indian Ocean, while the plain of the west and north makes the country open to Arctic and Atlantic influences.[152]

Most of Northwest Russia and Siberia has a subarctic climate, with extremely severe winters in the inner regions of Northeast Siberia (mostly Sakha, where the Northern Pole of Cold is located with the record low temperature of −71.2 °C or −96.2 °F), and more moderate winters elsewhere. Both the strip of land along the shore of the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Arctic islands have a polar climate.

The coastal part of Krasnodar Krai on the Black Sea, most notably in Sochi, possesses a humid subtropical climate with mild and wet winters. In many regions of East Siberia and the Far East, winter is dry compared to summer; other parts of the country experience more even precipitation across seasons. Winter precipitation in most parts of the country usually falls as snow. The region along the Lower Volga and Caspian Sea coast, as well as some areas of southernmost Siberia, possesses a semi-arid climate.

Throughout much of the territory, there are only two distinct seasons—winter and summer—as spring and autumn are usually brief periods of change between extremely low and extremely high temperatures.[152] The coldest month is January (February on the coastline); the warmest is usually July. Great ranges of temperature are typical. In winter, temperatures get colder both from south to north and from west to east. Summers can be quite hot, even in Siberia.[153]

Biodiversity

From north to south the East European Plain, is clad sequentially in Arctic tundra, taiga, mixed and broad-leaf forests, steppe, and semi-desert (fringing the Caspian Sea), as the changes in vegetation reflect the changes in climate. Siberia supports a similar sequence but is largely taiga. About half of Russia's total territory is forested, and it has the world's largest forest reserves, known as the "Lungs of Europe";[154] which is second only to the Amazon rainforest in the amount of carbon dioxide it absorbs.

There are 266 mammal species and 780 bird species in Russia. A total of 415 animal species were included in the RDBRF in 1997; and are now protected.[155] There are 40 UNESCO biosphere reserves,[156] 64 national parks and 101 nature reserves. Russia still has many ecosystems which are still untouched by man—mainly in the northern taiga areas, and in subarctic tundra of Siberia. Over time Russia has been having improvement and application of environmental legislation, development and implementation of various federal and regional strategies and programmes, and study, inventory and protection of rare and endangered plants, animals, and other organisms, and including them in the RDBRF.[157]

Economy

Russia has an upper-middle income mixed and transition economy,[158] with enormous natural resources, particularly oil and natural gas. It has the world's eleventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and the sixth-largest by PPP. According to the IMF, Russia's GDP per capita by PPP is $29,485 as of 2021.[9] The average nominal salary in Russia was ₽51,083 per month in 2020,[159] and approximately 12.9% of Russians lived below the national poverty line in 2018.[160] Unemployment in Russia was 4.5% in 2019,[161] and officially more than 70% of the Russian population is categorised as middle class;[162] though this is disputed.[163][164] By the end of December 2019, Russian foreign trade turnover reached $666.6 billion. Russia's exports totalled over $422.8 billion, while its imported goods were worth over $243.8 billion.[165] As of December 2020[update], foreign reserves in Russia are worth $444 billion.[166]

Oil, natural gas, metals, and timber account for more than 80% of Russian exports abroad.[124] In 2016, the oil-and-gas sector accounted for 36% of federal budget revenues.[167] In 2019, the Natural Resources and Environment Ministry estimated the value of natural resources to 60% of the country's GDP.[168] Russia has one of the lowest foreign debts among major economies.[169] It ranked 28th of 190 countries in the 2019 Ease of Doing Business Index. Russia has a flat tax rate of 13%; with the world's second-most attractive personal tax system for single managers after the United Arab Emirates.[170] However, extreme inequality of household income and wealth in the country has also been noted.[171][172]

Infrastructure

Railway transport in Russia is mostly under the control of the state-run Russian Railways. The total length of common-used railway tracks exceeds 85,500 km (53,127 mi),[173] second only to the United States. The most renowned railway in Russia is the Trans-Siberian Railway, the longest railway-line in the world. As of 2016[update], Russia has 1,452.2 thousand km of roads;[174] and its road density is among the lowest in the world.[175] Much of Russia's inland waterways, which total 102,000 km (63,380 mi), are made up of natural rivers or lakes. Among Russia's 1,216 airports,[176] the busiest are Sheremetyevo, Domodedovo, and Vnukovo in Moscow, and Pulkovo in Saint Petersburg.

Major seaports of Russia include Rostov-on-Don on the Sea of Azov, Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, Astrakhan and Makhachkala on the Caspian Sea, Kaliningrad and Saint Petersburg on the Baltic Sea, Arkhangelsk on the White Sea, Murmansk on the Barents Sea, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. Russia is the world's sole country to operate nuclear-powered icebreakers, which advance the economic exploitation of the Arctic continental shelf of Russia, and the development of sea trade through the Northern Sea Route.[177]

Russia is described as an energy superpower,[178] with the world's largest natural gas reserves,[179] the second-largest coal reserves,[180] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[181] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[182] It is the world's leading natural gas exporter,[183] the second-largest natural gas producer,[184] the second-largest oil exporter,[185] and the third-largest oil producer.[186] Fossil fuels cause most of the greenhouse gas emissions by Russia.[187] The country is the world's fourth-largest electricity producer,[188] and the ninth-largest renewable energy producer in 2019.[189] Russia was also the world's first country to develop civilian nuclear power, and to construct the first nuclear power plant. In 2019, It was the world's fourth-largest nuclear energy producer.[190]

Agriculture and fishery

Russia has the fourth-largest cultivated area in the world, at 1,237,294 square kilometres (477,722 sq mi); possessing 7.4% of the world's total arable land.[191] It is the third-largest grain exporter;[192] and is the top producer of barley, buckwheat and oats, and one of the largest producers and exporters of rye, and sunflower seed. Since 2016, Russia is the largest exporter of wheat in the world.[193]

While large farms concentrate mainly on grain production and animal husbandry, while small private household plots produce most of the country's potatoes, vegetables and fruits.[194] Russia is the home to the finest caviar in the world;[195] and maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets, ranking sixth in the world in tonnage of fish caught; capturing 4,773,413 tons of fish in 2018.[196]

Science and technology

Russia's research and development budget is the ninth-highest in the world, with an expenditure of approximately 422 billion rubles on domestic research and development.[197] In 2019, Russia was ranked tenth worldwide in the number of scientific publications.[198] Since 1904, Nobel Prize were awarded to twenty-six Russian and Soviet people in physics, chemistry, medicine, economy, literature and peace.[199]

Mikhail Lomonosov proposed the law of conservation of matter preceding the energy conservation law.[200] Since the time of Nikolay Lobachevsky (the "Copernicus of Geometry" who pioneered the non-Euclidean geometry) and a prominent tutor Pafnuty Chebyshev, the Russian mathematical school became one of the most influential in the world.[201] Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of modern chemistry.[200] Nine Soviet/Russian mathematicians were awarded with the Fields Medal.[202] Grigori Perelman was offered the first ever Clay Millennium Prize Problems Award for his final proof of the Poincaré conjecture in 2002.[203] Russian discoveries and inventions include the transformer, electric filament lamp, the aircraft, the safety parachute, sputnik, radio receiver, electrical microscope, colour photos,[204] caterpillar tracks, periodic table, track assembly, electrically powered railway wagons, videotape recorder, helicopter, solar cell, transformers, yogurt, television, petrol cracking, synthetic rubber and grain harvester.[205]

Roscosmos is Russia's national space agency; while Russian achievements in the field of space technology and space exploration are traced back to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the father of theoretical astronautics.[206] His works had inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers, such as Sergey Korolyov, Valentin Glushko, and many others who contributed to the success of the Soviet space program in the early stages of the Space Race and beyond.

In 1957, the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched; in 1961 the first human trip into space was successfully made by Yuri Gagarin. Many other Soviet and Russian space exploration records ensued, including the first spacewalk performed by Alexei Leonov, Luna 9 was the first spacecraft to land on the Moon, Zond 5 brought the first Earthlings (two tortoises and other life forms) to circumnavigate the Moon, Venera 7 was the first to land on another planet (Venus), Mars 3 then the first to land on Mars, the first space exploration rover Lunokhod 1, and the first space station Salyut 1 et Mir. Russia is the largest satellite launcher.[207]

Russia has completed the GLONASS satellite navigation system, and is developing its own fifth-generation jet fighter and constructing the first serial mobile nuclear plant in the world. Soyuz rockets are the only provider of transport for astronauts at the International Space Station. Luna-Glob is a Russian Moon exploration programme, with first planned mission launch in 2021. Roscosmos is also developing the Orel spacecraft, to replace the aging Soyuz, it could also conduct mission to lunar orbit as early as 2026.[208] In February 2019, it was announced that Russia is intending to conduct its first crewed mission to land on the Moon in 2031.[209]

Tourism

According to the World Tourism Organization, Russia was the sixteenth-most visited country in the world, and the tenth-most visited country in Europe, in 2018, with over 24.6 million visits.[210] Russia was ranked 39th in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019.[211] According to Federal Agency for Tourism, the number of inbound trips of foreign citizens to Russia amounted to 24.4 million in 2019.[212] Russia's international tourism receipts in 2018 amounted to $11.6 billion.[210] In 2020, tourism accounted for about 4% of country's GDP.[213] Major tourist routes in Russia include a journey around the Golden Ring of Russia, a theme route of ancient Russian cities, cruises on large rivers like the Volga, and journeys on the famous Trans-Siberian Railway.[214] Russia's most visited and popular landmarks include Red Square, the Peterhof Palace, the Kazan Kremlin, the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius and Lake Baikal.[215]

Demographics

Russia is one of the most sparsely populated and urbanised countries in the world; it had a population of 142.8 million according to the 2010 census,[216] which rose to 146.2 million as of 2021.[8] It is the most populous country in Europe, and the ninth-most populous country in the world; with a population density of 9 inhabitants per square kilometre (23 per square mile).

Since the 1990s, Russia's death rate has exceeded its birth rate.[217] In 2018, the total fertility rate across Russia was estimated to be 1.6 children born per woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1, and is one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. Subsequently, the nation has one of the oldest populations in the world, with an median age of 40.3 years.[218] In 2009, it recorded annual population growth for the first time in fifteen years; and since the 2010s, Russia has seen increased population growth due to declining death rates, increased birth rates and increased immigration.[219]

Russia is a multinational state, home to over 193 ethnic groups nationwide.[220] In the 2010 Census, roughly 81% of the population were ethnic Russians,[220] and rest of the 19% of the population were peoples of diverse origins,[3] while roughly 85% of Russia's population was of European descent,[3] of which the vast majority were Slavs, with a substantial minority of Finno-Ugric, Germanic, and other peoples. There are 22 republics in Russia, designated to have their own ethnicities, cultures, and languages. In 13 of them, ethnic Russians consist a minority. According to the United Nations, Russia's immigrant population is the third-largest in the world, numbering over 11.6 million;[221] most of which are from post-Soviet states, mainly Ukrainians.[222]

|

Largest cities or towns in Russia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Nom | Federal subject | Pop. | Rank | Nom | Federal subject | Pop. | ||

Saint Petersburg |

1 | Moscow | Moscow | [225]12,381,000 | 11 | Rostov-na-Donu | Rostov Oblast | 1,120,000 |  Novosibirsk  Yekaterinburg |

| 2 | Saint Petersburg | Saint Petersburg | [225]5,282,000 | 12 | Krasnoyarsk | Krasnoyarsk Krai | [226]1,084,000 | ||

| 3 | Novosibirsk | Novosibirsk Oblast | [227]1,603,000 | 13 | Perm | Perm Krai | 1,042,000 | ||

| 4 | Yekaterinburg | Sverdlovsk Oblast | [228]1,456,000 | 14 | Voronezh | Voronezh Oblast | 1,032,000 | ||

| 5 | Nizhny Novgorod | Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 1,267,000 | 15 | Volgograd | Volgograd Oblast | 1,016,000 | ||

| 6 | Kazan | Tatarstan | [229]1,232,000 | 16 | Krasnodar | Krasnodar Krai | [230]881,000 | ||

| 7 | Chelyabinsk | Chelyabinsk Oblast | [231]1,199,000 | 17 | Saratov | Saratov Oblast | 843,000 | ||

| 8 | Omsk | Omsk Oblast | [232]1,178,000 | 18 | Tolyatti | Samara Oblast | [233]711,000 | ||

| 9 | Samara | Samara Oblast | [233]1,170,000 | 19 | Izhevsk | Udmurtia | [234]646,000 | ||

| dix | Ufa | Bashkortostan | [235]1,126,000 | 20 | Ulyanovsk | Ulyanovsk Oblast | 622,000 | ||

Langue

Russia's official language is Russian. However, Russia's 193 minority ethnic groups speak over 100 languages.[236] According to the 2002 Census, 142.6 million people speak Russian, followed by Tatar with 5.3 million, and Ukrainian with 1.8 million speakers.[237] The constitution gives the individual republics of the country the right to establish their own state languages in addition to Russian.[238]

Russian is the most spoken native language in Europe, the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia, as well as the most widely spoken Slavic language in the world.[239] It belongs to the Indo-European language family, is one of the living members of the East Slavic languages, and is among the larger Balto-Slavic languages. It is the second-most used language on the Internet after English,[240] one of two official languages aboard the International Space Station,[241] and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[242]

Religion

Russia is a secular state by constitution, and its largest religion is Christianity. It has the world's largest Orthodox population.[244][245] As of a different sociological surveys on religious adherence; between 41% to over 80% of the total population of Russia adhere to the Russian Orthodox Church.[246][247][248]

In 2017, a survey made by the Pew Research Center showed that 73% of Russians declared themselves Christians—including 71% Orthodox, 1% Catholic, and 2% Other Christians, while 15% were unaffiliated, 10% were Muslims, and 1% were from other religions.[4] According to various reports, the proportion of Atheists in Russia is between 16% and 48% of the population.[249]

Islam is the second-largest religion in Russia.[250] It is the traditional and predominant religion amongst the peoples of the North Caucasus, and amongst some Turkic peoples scattered along the Volga-Ural region. Buddhists are home to a sizeable population in four republics of Russia: Buryatia, Tuva, Zabaykalsky Krai, and Kalmykia; the only region in Europe where Buddhism is the most practised religion.[251] Judaism has been a minority faith in Russia, as the country is home to a historical Jewish population, which is among the largest in Europe.[252] In the recent years, Hinduism has also seen an increase in followers in Russia.[253]

Éducation

Russia has the highest college-level or higher graduates in terms of percentage of population in the world, at 54%.[254] It has a free education system, which is guaranteed for all citizens by the constitution.[255] Since 1990, the 11-year school education has been introduced. Education in state-owned secondary schools is free. University-level education is free, with exceptions. A substantial share of students are enrolled for full pay (many state institutions started to open commercial positions in the last years).[256]

The oldest and largest universities in Russia are Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University. In the 2000s, in order to create higher education and research institutions of comparable scale in Russian regions, the government launched a program of establishing federal universities, mostly by merging existing large regional universities and research institutes and providing them with special funding. These new institutions include the Southern Federal University, Siberian Federal University, Kazan Volga Federal University, North-Eastern Federal University, and Far Eastern Federal University.

Santé

The constitution of Russia guarantees free, universal health care for all Russian citizens,[257] through a compulsory state health insurance program.[258] The Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation oversees the Russian public healthcare system, and the sector employs more than two million people.[258] Federal regions also have their own departments of health that oversee local administration.[258] Russia has the highest number of physicians, hospitals, and health care workers in the world on a per capita basis.[259]

According the World Bank, Russia spent 5.32% of its GDP on healthcare in 2018.[260] It has one of the world's most female-biased sex ratios, with 0.859 males to every female.[124] In 2019, the overall life expectancy in Russia at birth is 73.2 years (68.2 years for males and 78.0 years for females),[261] and it had a very low infant mortality rate (5 per 1,000 live births).[262] Obesity is a major health issue in Russia. In 2016, 61.1% of Russian adults were overweight or obese, while 23.1% were obese.[263] In 2017, roughly 16% of Russia's deaths were attributed to obesity, while per 100,000 Russians, 123 died due to being obese.[263]

Culture

Art and architecture

Early Russian painting is represented in icons and vibrant frescos. As Moscow rose to power, Theophanes the Greek, Dionisius and Andrei Rublev became vital names in Russian art. The Russian Academy of Arts was created in 1757. In the 18th century, academicians Ivan Argunov, Dmitry Levitzky, Vladimir Borovikovsky became influential. The early 19th century saw many prominent paintings by Karl Briullov and Alexander Ivanov. In the mid-19th century, the group of mostly realists Peredvizhniki broke with the Academy. Leading Russian realists include Ivan Shishkin, Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ivan Kramskoi, Vasily Polenov, Isaac Levitan, Vasily Surikov, Viktor Vasnetsov, Ilya Repin, and Boris Kustodiev. The turn of the 20th century saw the rise of symbolism; represented by Mikhail Vrubel, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, and Nicholas Roerich. The Russian avant-garde flourished from approximately 1890 to 1930; notable artists from this era were El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marc Chagall. Some influential Soviet sculptures were Vera Mukhina, Yevgeny Vuchetich and Ernst Neizvestny.

Beginning with the woodcraft buildings of ancient Slavs; since the Christianization of Kievan Rus', for several centuries Russian architecture was influenced predominantly by Byzantine architecture. Aristotle Fioravanti and other Italian architects brought Renaissance trends into Russia. The 16th century saw the development of the unique tent-like churches; and the onion dome design. In the 17th century, the "fiery style" of ornamentation flourished in Moscow and Yaroslavl, gradually paving the way for the Naryshkin baroque of the 1690s. After the reforms of Peter the Great; the country's architecture became influenced by Western Europe. The 18th-century taste for Rococo architecture led to the splendid works of Bartolomeo Rastrelli and his followers. During the reign of Catherine the Great and her grandson Alexander I, the city of Saint Petersburg was transformed into an outdoor museum of Neoclassical architecture. The second half of the 19th century was dominated by the Byzantine and Russian Revival style. Prevalent styles of the 20th century were the Art Nouveau (Fyodor Shekhtel), Constructivism (Moisei Ginzburg and Victor Vesnin), and Socialist Classicism (Boris Iofan).

Musique

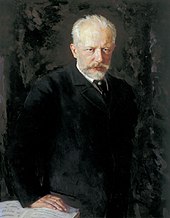

Music in 19th-century Russia was defined by the tension between classical composer Mikhail Glinka along with other members of The Mighty Handful, and the Russian Musical Society led by composers Anton and Nikolay Rubinstein. The later tradition of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era, was continued into the 20th century by Sergei Rachmaninoff, one of the last great champions of the Romantic style of European classical music.[264] World-renowned composers of the 20th century include Alexander Scriabin, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Georgy Sviridov and Alfred Schnittke.

Russian conservatories have turned out generations of famous soloists. Among the best known are violinists Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Leonid Kogan, Gidon Kremer, and Maxim Vengerov; cellists Mstislav Rostropovich, Natalia Gutman; pianists Vladimir Horowitz, Sviatoslav Richter, Emil Gilels, Vladimir Sofronitsky and Evgeny Kissin; and vocalists Fyodor Shalyapin, Mark Reizen, Elena Obraztsova, Tamara Sinyavskaya, Nina Dorliak, Galina Vishnevskaya, Anna Netrebko and Dmitry Hvorostovsky.[265]

Modern Russian rock music takes its roots both in the Western rock and roll and heavy metal, and in traditions of the Russian bards of the Soviet era, such as Vladimir Vysotsky and Bulat Okudzhava.[266] Russian pop music developed from what was known in the Soviet times as estrada into a full-fledged industry.

Literature and philosophy

Russian literature is considered to be among the most influential and developed in the world. It can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in Old East Slavic were composed. In the 18th century, by the Age of Enlightenment, the works of Mikhail Lomonosov and Denis Fonvizin boosted Russian literature. The early 19th century began with Vasily Zhukovsky and Alexander Pushkin; who is considered by many to be the greatest Russian poet.[267] It continued with the poetry of Mikhail Lermontov and Nikolay Nekrasov, dramas of Alexander Ostrovsky and Anton Chekhov, and the prose of Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ivan Goncharov, Aleksey Pisemsky and Nikolai Leskov. Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky have been described by as the greatest novelists of all time.[268][269] The next several decades had leading authors such as Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Alexander Blok, Nikolay Gumilyov, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Anna Akhmatova, and Boris Pasternak; and novelists Leonid Andreyev, Ivan Bunin, and Maxim Gorky.

Russian philosophy blossomed in the 19th century; with the works of Nikolay Danilevsky and Konstantin Leontiev. Notable philosophers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries include Vladimir Solovyov, Sergei Bulgakov, Pavel Florensky, Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Lossky, and Vladimir Vernadsky.

Following the 1917 revolution, and the ensuing civil war, many prominent writers and philosophers left the country; while a new generation of authors joined together in an effort to create a distinctive working-class culture appropriate for the new Soviet state. Leading authors of the Soviet era include novelists Yevgeny Zamiatin, Isaac Babel, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ilf and Petrov, Yury Olesha, Mikhail Bulgakov, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, and Andrei Voznesensky.

Cuisine

Russian cuisine has been formed by climate, cultural and religious traditions, and the vast geography of the nation.[271] It shares many similarities with cuisines of its neighbouring countries, and widely uses vegetables, fish, flour, cereals, bread,[272] and berries.[273]

Crops of rye, wheat, barley, and millet provide the ingredients for various breads, pancakes and cereals, as well as for many drinks. Black bread is very popular in Russia.[272] Flavourful soups and stews include shchi, borsch, ukha, solyanka and okroshka.[273] Smetana (a heavy sour cream) is often added to soups and salads.[274] Pirozhki, blini and syrniki are native types of pancakes.[273] Beef Stroganoff, Chicken Kiev, pelmeni and shashlyk are popular meat dishes.[275] Other meat dishes include stuffed cabbage rolls (golubtsy) usually filled with meat.[276] Salads include Olivier salad, vinegret and dressed herring.[275]

Russia's national non-alcoholic drink is Kvass,[270] and the national alcoholic drink is vodka;[277] its creation in the nation dates back to the 14th century.[278] The country has the world's highest vodka consumption,[279] but beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in Russia.[280] Wine has become popular in Russia in the last decade,[281][282] and the country is becoming one of the world's largest wine producers.[280][283]

Médias

The largest internationally operating news agencies in Russia are TASS, RIA Novosti, and Interfax.[284] Television is the most popular media in Russia, with 74% of the population watching national television channels routinely, and 59% routinely watching regional channels.[285] There are three main nationwide radio stations in Russia: Radio Russia, Radio Mayak, and Radio Yunost. Russia has the largest video gaming market in Europe, with over 65 million players nationwide.[286]

Russian and later Soviet cinema was a hotbed of invention, resulting in world-renowned films such as The Battleship Potemkin. Soviet-era filmmakers, most notably Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky, would become some of the world's most innovative and influential directors. Lev Kuleshov developed the Soviet montage theory; and Dziga Vertov's "film-eye" theory had a huge impact on the development of documentary filmmaking and cinema realism. Many Soviet socialist realism films were artistically successful, including Chapaev, The Cranes Are Flying, et Ballad of a Soldier.