Norvège – Wikipedia

Pays d'Europe du Nord

|

Royaume de norvège |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

Devise:

Enchant og tro inntil Dovre faller (Bokmål) Einige og tru inntil Dovre est tombé (Nynorsk) "Unis et loyaux jusqu'à la chute de Dovre" |

|

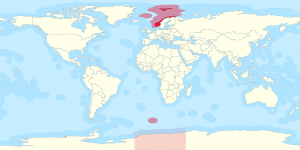

Montrer la carte de l'Europe

Localisation du royaume de Norvège

en Europe (vert et gris foncé) |

|

|

|

| Capitale

et la plus grande ville |

Oslo 59 ° 56′N 10 ° 41′E/59,933 ° N 10,683 ° E |

| Langues officielles | |

| Langues minoritaires officielles | |

| Système d'écriture | Latin |

| Groupes ethniques |

Statut autochtone: Statut de minorité:[4] |

| Demonym (s) | norvégien |

| Gouvernement | Monarchie constitutionnelle parlementaire unitaire |

| Harald V | |

| Erna Solberg | |

| Tone W. Trøen | |

| Toril Marie Øie | |

| Conservateur | |

| Corps législatif | Stortinget L Sámediggi |

| L'histoire | |

| 872 | |

| 1263 | |

| 1397 | |

| 1524 | |

| 25 février 1814 | |

| 17 mai 1814 | |

| 4 novembre 1814 | |

| 7 juin 1905 | |

| Surface | |

|

• Total |

385 207 km2 (148 729 milles carrés)[6] (67èmeune) |

|

• Eau (%) |

5.7b |

| Population | |

|

• estimation 2019 |

|

|

• Densité |

13,8 / km2 (35,7 / sq mi) (213e) |

| PIB (PPP) | Estimation 2018 |

|

• Total |

397 milliards de dollars[8] (46ème) |

|

• par habitant |

74 065 $[8] (4ème) |

| PIB (nominal) | Estimation 2018 |

|

• Total |

443 milliards de dollars[8] (22ème) |

|

• par habitant |

82 711 $[8] (3ème) |

| Gini (2017) | faible · 1er |

| HDI (2017) | très haut · 1er |

| Devise | Couronne norvégienne (NOK) |

| Fuseau horaire | UTC + 1 (CET) |

| UTC + 2 (CEST) | |

| Format de date | jj.mm.aaaa |

| Côté conduite | droite |

| Code d'appel | +47 |

| Code ISO 3166 | NON |

| TLD Internet | .nonc |

|

|

Norvège (Norvégien: ![]() Norge (Bokmål) ou

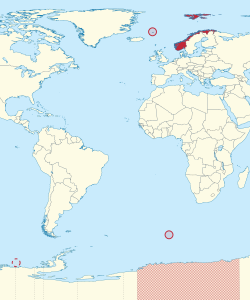

Norge (Bokmål) ou ![]() Noreg (Nynorsk); Sami du Nord: Norga; Sami du Sud: Nöörje; Lule Sami: Vuodna), officiellement le Royaume de norvège, est un pays nordique d’Europe du Nord dont le territoire comprend la partie occidentale et la plus septentrionale de la péninsule scandinave; l'île isolée de Jan Mayen et l'archipel de Svalbard font également partie du Royaume de Norvège.[note 1] L’île Antarctique Peter I et l’île sub-antarctique Bouvet sont des territoires dépendants et ne font donc pas partie du royaume. La Norvège revendique également une partie de l'Antarctique appelée Terre de la Reine Maud.

Noreg (Nynorsk); Sami du Nord: Norga; Sami du Sud: Nöörje; Lule Sami: Vuodna), officiellement le Royaume de norvège, est un pays nordique d’Europe du Nord dont le territoire comprend la partie occidentale et la plus septentrionale de la péninsule scandinave; l'île isolée de Jan Mayen et l'archipel de Svalbard font également partie du Royaume de Norvège.[note 1] L’île Antarctique Peter I et l’île sub-antarctique Bouvet sont des territoires dépendants et ne font donc pas partie du royaume. La Norvège revendique également une partie de l'Antarctique appelée Terre de la Reine Maud.

La Norvège a une superficie totale de 385 207 kilomètres carrés.[6] et une population de 5 312 300 (en août 2018).[12] Le pays partage une longue frontière orientale avec la Suède (1 619 km ou 1 006 mi). La Norvège est bordée au nord-est par la Finlande et la Russie, et au sud par le détroit de Skagerrak, avec le Danemark de l'autre côté. La Norvège a un littoral étendu, faisant face à l'océan Atlantique nord et à la mer de Barents.

Harald V de la maison de Glücksburg est l'actuel roi de Norvège. Erna Solberg est Premier ministre depuis 2013, année où elle a remplacé Jens Stoltenberg. État souverain unitaire doté d'une monarchie constitutionnelle, la Norvège répartit le pouvoir entre le parlement, le cabinet et la cour suprême, conformément à la constitution de 1814. Le royaume a été créé en 872 par la fusion d’un grand nombre de petits royaumes et existe depuis 1147 ans. De 1537 à 1814, la Norvège faisait partie du royaume de Danemark-Norvège et de 1814 à 1905, elle était en union personnelle avec le royaume de Suède. La Norvège était neutre pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. La Norvège est restée neutre jusqu'en avril 1940, date à laquelle le pays a été envahi et occupé par l'Allemagne jusqu'à la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

La Norvège a des subdivisions administratives et politiques à deux niveaux: les comtés et les municipalités. Le peuple sâme a une certaine autodétermination et influence sur les territoires traditionnels grâce au Parlement sâme et à la loi sur le Finnmark. La Norvège entretient des relations étroites avec l’Union européenne et les États-Unis. La Norvège est un membre fondateur des Nations Unies, de l'OTAN, de l'Association européenne de libre-échange, du Conseil de l'Europe, du Traité sur l'Antarctique et du Conseil nordique. un membre de l'Espace économique européen, de l'OMC et de l'OCDE; et une partie de l'espace Schengen.

La Norvège maintient le modèle de protection sociale nordique avec des soins de santé universels et un système de sécurité sociale complet. Ses valeurs sont enracinées dans des idéaux égalitaires.[13] L’État norvégien détient des participations importantes dans des secteurs industriels clés, disposant de vastes réserves de pétrole, de gaz naturel, de minéraux, de bois d’œuvre, de fruits de mer et d’eau douce. L’industrie pétrolière représente environ un quart du produit intérieur brut (PIB) du pays.[14] Par habitant, la Norvège est le premier producteur mondial de pétrole et de gaz naturel en dehors du Moyen-Orient.[15][16]

Le pays a le quatrième revenu par habitant le plus élevé au monde sur les listes de la Banque mondiale et du FMI.[17] Sur la liste du PIB (PPA) de l'ICA de la CIA (estimation de 2015), qui comprend les territoires et les régions autonomes, la Norvège se classe au onzième rang.[18] Il possède le plus grand fonds souverain du monde, d'une valeur de 1 billion de dollars américains.[19] La Norvège affiche le meilleur indice de développement humain au monde depuis 2009, une position également occupée auparavant entre 2001 et 2006.[20] Il avait également le classement le plus élevé corrigé des inégalités[21][22][23] jusqu'en 2018, date à laquelle l'Islande est passée en haut de la liste.[24] La Norvège au premier rang du World Happiness Report 2017[25] et se classe actuellement au premier rang de l’indice Better Life de l’OCDE, de l’indice d’intégrité publique et de l’indice de la démocratie.[26] La Norvège a l'un des taux de criminalité les plus bas au monde.[27]

Étymologie

La Norvège a deux noms officiels: Norge à Bokmål et Noreg à Nynorsk. Le nom anglais Norway vient du vieux mot anglais Norweg mentionné en 880, signifiant "voie du nord" ou "voie menant au nord", c'est ainsi que les anglo-saxons se référaient au littoral de la Norvège atlantique[28][29] semblable à un consensus scientifique sur l'origine du nom de la langue norvégienne.[30] Les Anglo-Saxons de Grande-Bretagne ont également qualifié le royaume de Norvège en 880 Terre Norðmanna.[28][29]

Il existe un certain désaccord sur le point de savoir si le nom autochtone de Norvège avait à l'origine la même étymologie que la forme anglaise. Selon la vision dominante traditionnelle, le premier composant était à l’origine norðr, un proche de l'anglais Nord, donc le nom complet était Non seulement, "le chemin du nord", faisant référence à la route de navigation le long de la côte norvégienne et contrastant avec suðrvegar "voie méridionale" (du vieux norrois suðr) pour (Allemagne), et austrvegr "voie orientale" (de l'austr) pour la Baltique. Dans la traduction de Orosius pour Alfred, le nom est Norðweg, alors que dans les sources anciennes en anglais ancien, le ð a disparu.[31] Au 10ème siècle, de nombreux nordiques s’établirent dans le nord de la France, d’après les sagas, dans la région appelée plus tard Normandie Norðmann (Norseman ou scandinave[32][33]), mais pas une possession norvégienne.[34] En France Normanni ou Northmanni personnes visées de la Norvège, la Suède ou le Danemark.[35] Jusque vers 1800, les habitants de la Norvège occidentale étaient appelés Nordmenn (habitants du nord), tandis que les habitants de l’est de la Norvège étaient appelés austmenn (hommes de l'est).[36]

Selon une autre théorie, le premier composant était un mot ni, signifiant "étroit" (ancien anglais près de) ou "nord", en référence à la voie de navigation terrestre de l'archipel ("voie étroite"). L'interprétation comme "nordique", comme en témoignent les formes anglaise et latine du nom, aurait alors été due à une étymologie populaire postérieure. Ce dernier point de vue a été créé par le philologue Niels Halvorsen Trønnes en 1847; depuis 2016, il a également été défendu par l'étudiant en langues et militant Klaus Johan Myrvoll et a été adopté par le professeur de philologie Michael Schulte.[28][29] La forme Nore est encore utilisé dans des noms de lieux tels que le village de Nore et le lac Norefjorden dans le comté de Buskerud, et a toujours la même signification.[28][29] Parmi les autres arguments en faveur de la théorie, il est souligné que le mot a une longue voyelle dans la poésie skaldique et n’est pas attesté par <ð> dans des textes ou des inscriptions nordiques indigènes (les premières attestations runiques sont orthographiées Nuruiak et Nuriki). Cette théorie ressuscitée a été quelque peu rejetée par d'autres spécialistes pour divers motifs, e. g. la présence incontestée de l'élément norðr dans l'ethnonyme norðrmaðr "Norseman, personne norvégienne" (norvégien moderne Nordmann), et l'adjectif Norrǿnn "nord, norrois, norvégien", ainsi que les toutes premières attestations des formes latines et anglo-saxonnes avec

Dans un manuscrit latin de 849, le nom Northuagia est mentionné, alors qu'une chronique française de c. 900 utilise les noms Northwegia et Norvège.[37] Quand Ohthere de Hålogaland a rendu visite au roi Alfred le Grand en Angleterre à la fin du neuvième siècle, le pays s'appelait Norðwegr (littéralement "Northway") et Norðmanna Land (littéralement "terre des hommes du nord").[37] Selon Ohthere, Norðmanna vivaient le long de la côte atlantique, les Danois autour de Skagerrak og Kattegat, tandis que les Sames (les "Fins") avaient un style de vie nomade dans le vaste intérieur.[38][39] Ohthere a dit à Alfred qu'il était "le plus septentrional de tous les Norvégiens", probablement sur l'île de Senja ou plus près de Tromsø. Il a également déclaré qu'au-delà des vastes étendues sauvages du sud de la Norvège, se trouvait le pays des Suédois, "Svealand".[40][41]

L'adjectif norvégien, enregistré de c. 1600, est dérivé de la latinisation du nom en tant que Norvège; dans l'adjectif norvégien, le vieil anglais orthographe '-weg' a survécu.[42]

Après que la Norvège soit devenue chrétienne, Noregr et Noregi sont devenues les formes les plus courantes, mais au cours du 15ème siècle, les nouvelles formes Noreg (h) et Norg (h) e, retrouvés dans des manuscrits islandais médiévaux, ont pris le relais et ont survécu jusqu'à nos jours.[[citation requise]

L'histoire

Préhistoire

Les premiers habitants furent la culture d'Ahrensburg (du 11ème au 10ème millénaire avant notre ère), une culture du Paléolithique supérieur tardif du Dryas plus jeune, la dernière période de froid à la fin de la glaciation de Weichselian. La culture tire son nom du village d'Ahrensburg, situé à 25 km au nord-est de Hambourg, dans l'État allemand du Schleswig-Holstein, où des fûts de flèche et des massues en bois ont été mis à jour.[43] Les traces les plus anciennes d’occupation humaine en Norvège se trouvent le long de la côte, où l’immense plateau de glace de la dernière période glaciaire a fondu pour la première fois entre 11 000 et 8 000 ans av. Les plus anciennes découvertes sont des outils de pierre datant de 9 500 à 6 000 ans avant JC, découverts dans le Finnmark (culture de la Komsa) au nord et dans le Rogaland (culture de Fosna) au sud-ouest. Cependant, les théories sur deux cultures totalement différentes (la culture Komsa au nord du cercle polaire arctique et la culture Fosna de Trøndelag à Oslofjord étant l'autre) ont été rendues obsolètes dans les années 1970.

Des découvertes plus récentes le long de toute la côte ont révélé aux archéologues que la différence entre les deux pouvait tout simplement être attribuée à différents types d'outils et non à des cultures différentes. La faune côtière constituait un moyen de subsistance pour les pêcheurs et les chasseurs, qui auraient pu se frayer un chemin le long de la côte sud vers 10 000 ans avant notre ère, alors que l'intérieur était encore recouvert de glace. On pense maintenant que ces peuples dits "arctiques" sont venus du sud et ont suivi la côte vers le nord beaucoup plus tard.

Dans la partie méridionale du pays, des sites d'habitation datant d'environ 5 000 ans av. Les découvertes de ces sites donnent une idée plus précise de la vie des peuples chasseurs et pêcheurs. Les outils varient en forme et sont principalement constitués de différents types de pierre; ceux des périodes ultérieures sont plus habiles. Des gravures rupestres (pétroglyphes, par exemple) ont été découvertes, généralement près des terrains de chasse et de pêche. Ils représentent des gibiers comme le cerf, le renne, le wapiti, les ours, les oiseaux, les phoques, les baleines et les poissons (en particulier le saumon et le flétan), qui étaient tous essentiels au mode de vie des populations côtières. Les gravures rupestres d'Alta dans le Finnmark, les plus grandes de Scandinavie, ont été réalisées au niveau de la mer de 4 200 à 500 av. J.-C. et marquent la progression de la terre à mesure que la mer montait après la fin de la dernière glaciation.

L'Âge de bronze

Entre 3000 et 2500 avant JC, de nouveaux colons (culture Corded Ware) sont arrivés dans l'est de la Norvège. C'étaient des agriculteurs indo-européens qui cultivaient des céréales et élevaient des vaches et des moutons. La population de chasseurs-pêcheurs de la côte ouest a également été progressivement remplacée par des agriculteurs, bien que la chasse et la pêche restent des moyens de subsistance secondaires utiles.

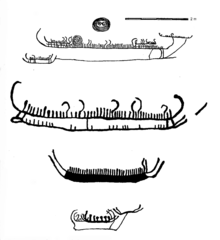

Vers 1500 av. J.-C., le bronze fut introduit progressivement, mais l'utilisation d'instruments de pierre continua. La Norvège avait peu de richesses à échanger contre des objets en bronze et les quelques trouvailles consistent principalement en armes sophistiquées et en broches que seuls les chefs pouvaient se permettre. D'énormes cairns funéraires construits près de la mer aussi au nord que Harstad et aussi à l'intérieur des terres au sud sont caractéristiques de cette période. Les motifs des gravures rupestres diffèrent de ceux typiques de l'âge de pierre. Les représentations du soleil, des animaux, des arbres, des armes, des navires et des personnages sont fortement stylisées.

Des milliers de gravures rupestres datant de cette période représentent des navires, et les grands monuments funéraires en pierre connus sous le nom de navires en pierre suggèrent que les navires et la navigation ont joué un rôle important dans la culture en général. Les navires représentés représentent très probablement des canoës construits en planches cousues, utilisés pour la guerre, la pêche et le commerce. Ces types de navires peuvent avoir leur origine dès la période néolithique et continuer jusqu’à l’âge du fer pré-romain, comme l’illustre le bateau Hjortspring.[44]

L'âge de fer

Peu de choses remontent au début de l'âge du fer (500 ans av. J.-C.). Les morts ont été incinérés et leurs tombes contiennent peu d'objets funéraires. Au cours des quatre premiers siècles de notre ère, le peuple norvégien était en contact avec la Gaule occupée par les Romains. Environ 70 chaudrons de bronze romains, souvent utilisés comme urnes funéraires, ont été retrouvés. Le contact avec les pays civilisés plus au sud a apporté une connaissance des runes; la plus ancienne inscription runique norvégienne connue date du 3ème siècle. A cette époque, le nombre de zones habitées dans le pays a augmenté, une évolution qui peut être suivie par des études coordonnées sur la topographie, l'archéologie et les noms de lieux. Les noms de racine les plus anciens, tels que nda, vik et bø ("cape", "baie" et "ferme") sont d'une grande antiquité, datant peut-être de l'âge du bronze, alors que le plus ancien des groupes de noms composés avec les suffixes vin ("prairie") ou heim ("colonie"), comme dans Bjǫrgvin (Bergen) ou Sǿheim (Seim), datent généralement du 1er siècle de notre ère.

Les archéologues ont d’abord pris la décision de diviser l’âge du fer de l’Europe du Nord en deux âges pré-romain et romain après la découverte par Emil Vedel de nombreux objets datant de l’âge du fer en 1866 sur l’île de Bornholm.[45] Ils n’ont pas exercé la même influence romaine que sur la plupart des autres artefacts des premiers siècles de notre ère, ce qui indique que certaines régions de l’Europe du Nord n’étaient pas encore entrées en contact avec les Romains au début de l’âge du fer.

Période de migration

La destruction de l'Empire romain d'Occident par les peuples germaniques au Ve siècle est caractérisée par de riches découvertes, notamment des tombes de chefs de tribus contenant de magnifiques armes et des objets en or.[[citation requise] Les forts des collines ont été construits sur des rochers escarpés pour se défendre. Les fouilles ont révélé des fondations en pierre de fermes de 18 à 27 mètres de long, voire de 46 mètres de long, dont les toits étaient soutenus par des poteaux en bois. Ces maisons étaient des fermes familiales où plusieurs générations vivaient ensemble, avec des gens et du bétail sous un même toit.[[citation requise]

Ces États étaient basés sur des clans ou des tribus (par exemple, le Horder of Hordaland dans l’ouest de la Norvège). Au IXe siècle, chacun de ces petits États avait des choses (assemblées locales ou régionales) pour la négociation et le règlement des litiges. le chose Les lieux de rencontre, chacun avec éventuellement un hörgr (sanctuaire à ciel ouvert) ou un païen hof (temple; littéralement "colline"), étaient généralement situés dans les fermes les plus anciennes et les meilleures, qui appartenaient aux chefs et aux agriculteurs les plus riches. Le régional des choses réunis pour former des unités encore plus grandes: assemblées de députés de plusieurs régions. De cette façon, le en retard (assemblées de négociation et de législation) développées. Le Gulant avait son lieu de rendez-vous près du Sognefjord et aurait pu être le centre d'une confédération aristocratique[[citation requise] le long des fjords et des îles occidentales appelés Gulatingslag. La Frostating était l’assemblée des dirigeants de la région de Trondheimsfjord; les comtes de Lade, près de Trondheim, semblent avoir élargi le Frostatingslag en ajoutant le littoral de Romsdalsfjord à Lofoten.[[citation requise]

Âge viking

Du 8ème au 10ème siècle, la région scandinave au sens large a été la source des Vikings. Le pillage du monastère de Lindisfarne dans le nord-est de l'Angleterre en 793 par des Nordiques a longtemps été considéré comme l'événement qui a marqué le début de l'âge viking.[46] Cet âge était caractérisé par l’expansion et l’émigration des marins vikings. Ils ont colonisé, perquisitionné et échangé dans toutes les régions d'Europe. Les explorateurs viking norvégiens ont découvert l'Islande par accident au IXe siècle, alors qu'ils se dirigeaient vers les îles Féroé, avant de rencontrer Vinland, aujourd'hui connu sous le nom de Terre-Neuve, au Canada. Les Vikings de Norvège étaient les plus actifs dans le nord et l'ouest des îles Britanniques et dans l'est des îles d'Amérique du Nord.[47]

Selon la tradition, Harald Fairhair les a unifiés en 872 après la bataille de Hafrsfjord à Stavanger, devenant ainsi le premier roi d'une Norvège unie.[48] Le royaume de Harald était principalement un État côtier du sud de la Norvège. Fairhair a gouverné avec une main forte et selon les sagas, de nombreux Norvégiens ont quitté le pays pour vivre en Islande, dans les îles Féroé, au Groenland et dans certaines parties de la Grande-Bretagne et de l'Irlande. Les villes irlandaises modernes telles que Dublin, Limerick et Waterford ont été fondées par des colons norvégiens.[49]

Les traditions nordiques ont été remplacées lentement par celles chrétiennes à la fin du 10ème et au début du 11ème siècle. Le traité conclu entre les Islandais et Olaf Haraldsson, roi de Norvège, entre 1015 et 1028, est l’une des sources les plus importantes de l’histoire des Vikings du XIe siècle.[50] Ceci est largement attribué aux rois missionnaires Olav Tryggvasson et St. Olav. Haakon le Bon fut le premier roi chrétien de Norvège au milieu du Xe siècle, bien que sa tentative d'introduire cette religion ait été rejetée. Né entre 963 et 969, Olav Tryggvasson partit en raid en Angleterre avec 390 navires. Il a attaqué Londres pendant ce raid. De retour en Norvège en 995, Olav atterrit à Moster. Là, il construisit une église qui devint la première église chrétienne jamais construite en Norvège. De Moster, Olav a navigué vers le nord à Trondheim où il a été proclamé roi de Norvège par les Eyrathing en 995.[51]

Le féodalisme ne s'est jamais vraiment développé en Norvège ou en Suède, comme dans le reste de l'Europe. Cependant, l'administration du gouvernement prit un caractère féodal très conservateur. La Ligue hanséatique a obligé la royauté à leur céder de plus en plus de concessions sur le commerce extérieur et l'économie. La Ligue avait cette emprise sur la royauté à cause des emprunts que la Hansa avait consentis à la royauté et de la lourde dette des rois. Le contrôle monopolistique de la Ligue sur l’économie de la Norvège a exercé des pressions sur toutes les classes, en particulier la paysannerie, au point qu’il n’existait pas de véritable classe bourgeoise en Norvège.[52]

Guerre civile et point culminant du pouvoir

Des années 1040 à 1130, le pays était en paix.[53] En 1130, l'ère de la guerre civile a éclaté sur la base de lois de succession peu claires, qui permettaient à tous les fils du roi de gouverner ensemble. Pendant des périodes, il pouvait y avoir de la paix avant qu'un fils de moindre rang ne s'allie avec un chef et engage un nouveau conflit. L'archidiocèse de Nidaros a été créé en 1152 et a tenté de contrôler la nomination des rois.[54] L’église devait inévitablement prendre parti dans les conflits, les guerres civiles devenant également un problème concernant l’influence du roi sur l’église. Les guerres ont pris fin en 1217 avec la nomination de Håkon Håkonsson, qui a introduit un droit de succession clair.[55]

De 1 000 à 1 300, la population est passée de 150 000 à 400 000 habitants, ce qui a entraîné à la fois davantage de terres défrichées et le lotissement de fermes. Alors que, à l'époque viking, tous les agriculteurs possédaient leur propre terre, en 1300, soixante-dix pour cent des terres appartenaient au roi, à l'église ou à l'aristocratie. Il s’agissait d’un processus progressif dû au fait que les agriculteurs empruntaient de l’argent en période de crise et ne pouvaient pas rembourser. Cependant, les locataires sont toujours restés des hommes libres et les grandes distances et la propriété souvent dispersée signifiaient qu'ils jouissaient de beaucoup plus de liberté que les serfs continentaux. Au XIIIe siècle, environ 20% du rendement d'un fermier revenait au roi, à l'église et aux propriétaires terriens.[56]

Le 14ème siècle est décrit comme l'âge d'or de la Norvège, avec la paix et l'augmentation des échanges commerciaux, en particulier avec les îles britanniques, bien que l'Allemagne devienne de plus en plus importante vers la fin du siècle. Tout au long du Haut Moyen Âge, le roi a établi la Norvège comme État souverain doté d'une administration centrale et de représentants locaux.[57]

En 1349, la peste noire se propagea en Norvège et avait tué un tiers de la population en un an. Des fléaux ultérieurs ont réduit la population à la moitié du point de départ d’ici à 1400. De nombreuses communautés ont été entièrement exterminées, ce qui a entraîné une abondance de terres, permettant aux agriculteurs de se reconvertir dans l’élevage. La réduction des impôts a affaibli la position du roi,[58] et beaucoup d'aristocrates ont perdu la base de leur surplus, en en réduisant certains à de simples agriculteurs. Les dîmes élevées à l'église la rendirent de plus en plus puissante et l'archevêque devint membre du Conseil d'État.[59]

La Ligue hanséatique prit le contrôle du commerce norvégien au 14ème siècle et créa un centre commercial à Bergen. En 1380, Olaf Haakonsson hérita des trônes norvégien et danois, créant ainsi une union entre les deux pays.[59] En 1397, sous Margaret I, l'Union de Kalmar fut créée entre les trois pays scandinaves. Elle a fait la guerre aux Allemands, ce qui a entraîné un blocus commercial et une taxation plus élevée des produits norvégiens, ce qui a entraîné une rébellion. Cependant, le Conseil d'État norvégien était trop faible pour se retirer de l'union.[60]

Margaret poursuivit une politique centralisatrice qui favorisa inévitablement le Danemark, car sa population était supérieure à celle de la Norvège et de la Suède.[61] Margaret a également accordé des privilèges commerciaux aux marchands hanséatiques de Lübeck à Bergen en échange de la reconnaissance de son droit de gouverner, ce qui a porté préjudice à l'économie norvégienne. Les marchands hanséatiques ont formé un État dans un État à Bergen pendant des générations.[62] Les pirates, les "Victual Brothers", ont lancé trois raids dévastateurs sur le port (le dernier en 1427).[63]

La Norvège a glissé de plus en plus au second plan sous la dynastie Oldenburg (créée en 1448). Il y a eu une révolte sous Knut Alvsson en 1502.[64] Les Norvégiens avaient de l'affection pour le roi Christian II, qui résidait dans le pays depuis plusieurs années. La Norvège n'a pas pris part aux événements qui ont conduit à l'indépendance de la Suède du Danemark dans les années 1520.[65]

Union de Kalmar

À la mort de Haakon V (roi de Norvège) en 1319, Magnus Erikson, âgé de trois ans à peine, hérite du trône sous le nom de roi Magnus VII de Norvège. En même temps, un mouvement visant à faire de Magnus le roi de Suède porte ses fruits et les rois de Suède et du Danemark sont élus au trône par leurs nobles respectifs. Ainsi, avec son élection sur le trône de Suède, de Suède et de Norvège ont été unis sous le roi Magnus VII.[66]

En 1349, la peste noire changea radicalement la Norvège, faisant entre 50% et 60% de sa population[67] et le laissant dans une période de déclin social et économique.[68] La peste a laissé la Norvège très pauvre. Bien que le taux de mortalité soit comparable à celui du reste de l'Europe, la reprise économique a pris beaucoup plus de temps en raison de la petite population dispersée.[68] Même avant la peste, la population n'était que d'environ 500 000 personnes.[69] Après la peste, de nombreuses fermes sont restées inactives alors que la population a augmenté lentement.[68] Cependant, les locataires des quelques exploitations agricoles survivantes ont constaté que leurs positions de négociation avec leurs propriétaires se trouvaient considérablement renforcées.[68]

Le roi Magnus VII régna sur la Norvège jusqu'en 1350, date à laquelle son fils, Haakon, fut placé sur le trône sous le nom de Haakon VI.[70] En 1363, Haakon VI épousa Margaret, fille du roi Valdemar IV du Danemark.[68] À la mort de Haakon VI, en 1379, son fils, Olaf IV, n’avait que 10 ans.[68] Olaf avait déjà été élu sur le trône du Danemark le 3 mai 1376.[68] Ainsi, lors de l'accession d'Olaf au trône norvégien, le Danemark et la Norvège sont devenus une union personnelle.[71] La reine Margaret, mère de Olaf et veuve d'Haakon, dirigeait les affaires étrangères du Danemark et de la Norvège pendant la minorité d'Olaf IV.[68]

Margaret travaillait à l’union de la Suède avec le Danemark et la Norvège en faisant élire Olaf au trône suédois. Elle était sur le point d'atteindre cet objectif quand Olaf IV est décédé subitement.[68] Cependant, le Danemark a nommé Margaret gouverneur provisoire à la mort d’Olaf. Le 2 février 1388, la Norvège emboîta le pas et couronna Margaret.[68] La reine Margaret savait que son pouvoir serait plus sûr si elle pouvait trouver un roi pour gouverner à sa place. Elle s'est installée sur Eric de Poméranie, petit-fils de sa soeur. C'est ainsi que lors d'une réunion scandinave à Kalmar, Erik de Poméranie fut couronné roi des trois pays scandinaves. Ainsi, la politique royale a abouti à des unions personnelles entre les pays nordiques, amenant finalement les trônes de la Norvège, du Danemark et de la Suède sous le contrôle de la reine Marguerite lorsque le pays est entré dans l'Union de Kalmar.

Union avec le Danemark

Après la sortie de la Suède de l’Union de Kalmar en 1521, la Norvège essaya de faire de même,[[citation requise] mais la rébellion suivante fut vaincue et la Norvège resta en union avec le Danemark jusqu'en 1814, soit 434 ans au total. Au cours du romantisme national du XIXe siècle, certains ont qualifié cette période de «nuit de 400 ans», puisque tout le pouvoir royal, intellectuel et administratif du royaume était centralisé à Copenhague, au Danemark. En fait, ce fut une période de grande prospérité et de progrès pour la Norvège, notamment en ce qui concerne le transport maritime et le commerce extérieur, et elle assura également la relance du pays après la catastrophe démographique qu'a connue la peste noire. Sur la base des ressources naturelles respectives, Danemark – Norvège constituait en réalité un très bon complément puisque le Danemark répondait aux besoins norvégiens en céréales et en produits alimentaires et que la Norvège fournissait du bois, du métal et du poisson au Danemark.

Avec l'introduction du protestantisme en 1536, l'archevêché de Trondheim fut dissout et la Norvège perdit son indépendance et devint effectivement une colonie du Danemark. Les revenus et les biens de l'Église ont plutôt été redirigés vers le tribunal de Copenhague. La Norvège a perdu le flot incessant de pèlerins au profit des reliques de Saint-Olav au sanctuaire de Nidaros, et avec eux une grande partie du contact avec la vie culturelle et économique du reste de l'Europe.

Finalement restauré en tant que royaume (bien qu'en union législative avec le Danemark) en 1661, la Norvège voit son territoire diminuer au 17ème siècle avec la perte des provinces de Båhuslen, Jemtland et Herjedalen en Suède, à la suite d'un certain nombre de guerres désastreuses. avec la Suède. Au nord, toutefois, son territoire a été élargi par l’acquisition des provinces septentrionales de Troms et de Finnmark, aux dépens de la Suède et de la Russie.

La famine de 1695-1696 a tué environ 10% de la population norvégienne.[72] La récolte a échoué en Scandinavie au moins neuf fois entre 1740 et 1800, entraînant de nombreuses pertes de vies humaines.[73]

Union avec la Suède

Après l'attaque du Danemark contre la Norvège par le Royaume-Uni lors de la bataille de Copenhague en 1807, le Royaume-Uni conclut une alliance avec Napoléon. La guerre mena à de terribles conditions et provoqua une famine massive en 1812. Le royaume danois se retrouvant du côté des perdants en 1814 Aux termes du traité de Kiel, il fut contraint de céder la Norvège au roi de Suède, tandis que les anciennes provinces norvégiennes d’Islande, du Groenland et des îles Féroé demeuraient sous la couronne danoise.[74] La Norvège saisit cette occasion pour déclarer son indépendance, adopta une constitution inspirée des modèles américain et français et élit le roi héritier du Danemark et de la Norvège, Christian Frederick, le 17 mai 1814 au rang de roi. C'est la célèbre fête de Syttende Mai (le 17 mai) célébré par les Norvégiens et les Américains norvégiens. Syttende Mai est aussi appelé Jour de la Constitution norvégienne.

L'opposition norvégienne à la décision des grandes puissances de lier la Norvège à la Suède provoqua l'éclatement de la guerre entre la Suède et la Suède alors que la Suède tentait de maîtriser la Norvège par des moyens militaires. L'armée suédoise n'étant pas assez forte pour vaincre les forces norvégiennes et le trésor de la Norvège n'étant pas assez important pour soutenir une guerre prolongée, les marines britanniques et russes bloquant la côte norvégienne,[75] les belligérants ont été forcés de négocier la Convention de Moss. Selon les termes de la convention, Christian Frederik a abdiqué le trône norvégien et autorisé le Parlement de Norvège à apporter les modifications constitutionnelles nécessaires pour permettre l'union personnelle que la Norvège a été forcée d'accepter. Le 4 novembre 1814, le Parlement (Storting) élit Charles XIII de Suède au rang de roi de Norvège, établissant ainsi l'union avec la Suède.[76] En vertu de cet arrangement, la Norvège a conservé sa constitution libérale et ses propres institutions indépendantes, à l'exception du service extérieur. À la suite de la récession provoquée par les guerres napoléoniennes, le développement économique de la Norvège demeura lent jusqu'au début de la croissance économique vers 1830.[77]

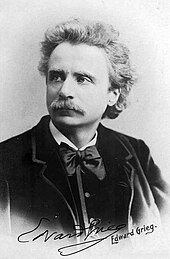

Cette période a également vu la montée du nationalisme romantique norvégien, alors que les Norvégiens cherchaient à définir et à exprimer un caractère national distinct. Le mouvement couvrait toutes les branches de la culture, y compris la littérature (Henrik Wergeland [1808–1845], Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson [1832–1910]Peter Christen Asbjørnsen [1812–1845], Jørgen Moe [1813–1882]), peinture (Hans Gude [1825–1903], Adolph Tidemand [1814–1876]), musique (Edvard Grieg [1843–1907]), et même la politique linguistique, où les tentatives de définition d’une langue maternelle autochtone en Norvège ont abouti aux deux formes écrites officielles en norvégien d’aujourd’hui: le Bokmål et le Nynorsk.

Le roi Charles III Jean, qui accéda au trône de Norvège et de Suède en 1818, fut le deuxième roi après la rupture de la Norvège avec le Danemark et son union avec la Suède. Charles John was a complex man whose long reign extended to 1844. He protected the constitution and liberties of Norway and Sweden during the age of Metternich. As such, he was regarded as a liberal monarch for that age. However, he was ruthless in his use of paid informers, the secret police and restrictions on the freedom of the press to put down public movements for reform—especially the Norwegian national independence movement.[78]

The Romantic Era that followed the reign of King Charles III John brought some significant social and political reforms. In 1854, women won the right to inherit property in their own right, just like men. In 1863, the last trace of keeping unmarried women in the status of minors was removed. Furthermore, women were then eligible for different occupations, particularly the common school teacher.[79] By mid-century, Norway's democracy was limited by modern standards: Voting was limited to officials, property owners, leaseholders and burghers of incorporated towns.[80]

Still, Norway remained a conservative society. Life in Norway (especially economic life) was "dominated by the aristocracy of professional men who filled most of the important posts in the central government".[81] There was no strong bourgeosie class in Norway to demand a breakdown of this aristocratic control of the economy.[82] Thus, even while revolution swept over most of the countries of Europe in 1848, Norway was largely unaffected by revolts that year.[82]

Marcus Thrane was a Utopian socialist. He made his appeal to the labouring classes urging a change of social structure "from below upwards." In 1848, he organised a labour society in Drammen. In just a few months, this society had a membership of 500 and was publishing its own newspaper. Within two years, 300 societies had been organised all over Norway, with a total membership of 20,000 persons. The membership was drawn from the lower classes of both urban and rural areas; for the first time these two groups felt they had a common cause.[83] In the end, the revolt was easily crushed; Thrane was captured and in 1855, after four years in jail, was sentenced to three additional years for crimes against the safety of the state. Upon his release, Marcus Thrane attempted unsuccessfully to revitalise his movement, but after the death of his wife, he migrated to the United States.[84]

In 1898, all men were granted universal suffrage, followed by all women in 1913.

Dissolution of the union

Christian Michelsen, a shipping magnate and statesman, and Prime Minister of Norway from 1905 to 1907, played a central role in the peaceful separation of Norway from Sweden on 7 June 1905. A national referendum confirmed the people's preference for a monarchy over a republic. No Norwegian could legitimately claim the throne because none was able to prove relationship to medieval royalty and in European tradition royal or "blue" blood is a precondition for laying claim to the throne.

The government offered the throne of Norway to a prince of the Dano-German royal house of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. Prince Carl of Denmark was unanimously elected king by the Norwegian Parliament, the first king of a fully independent Norway in 508 years (1397: Kalmar Union); he took the name Haakon VII. In 1905, the country welcomed the prince from neighbouring Denmark, his wife Maud of Wales and their young son to re-establish Norway's royal house. Following centuries of close ties between Norway and Denmark, a prince from the latter was the obvious choice for a European prince who could best relate to the Norwegian people.

First and Second World Wars

Throughout the First World War, Norway was in principle a neutral country. In reality, however, Norway had been pressured by the British to hand over increasingly large parts of its large merchant fleet to the British at low rates, as well as to join the trade blockade against Germany. Norwegian merchant marine ships, often with Norwegian sailors still on board, were then sailing under the British flag and at risk of being sunk by German submarines. Thus, many Norwegian sailors and ships were lost. Thereafter, the world ranking of the Norwegian merchant navy fell from fourth place to sixth in the world.[85]

Norway also proclaimed its neutrality during the Second World War, but despite this, it was invaded by German forces on 9 April 1940. Although Norway was unprepared for the German surprise attack (see: Battle of Drøbak Sound, Norwegian Campaign, and Invasion of Norway), military and naval resistance lasted for two months. Norwegian armed forces in the north launched an offensive against the German forces in the Battles of Narvik, until they were forced to surrender on 10 June after losing British support which had been diverted to France during the German invasion of France.

King Haakon and the Norwegian government escaped to Rotherhithe in London. Throughout the war they sent inspirational radio speeches and supported clandestine military actions in Norway against the Germans. On the day of the invasion, the leader of the small National-Socialist party Nasjonal Samling, Vidkun Quisling, tried to seize power, but was forced by the German occupiers to step aside. Real power was wielded by the leader of the German occupation authority, Reichskommissar Josef Terboven. Quisling, as minister president, later formed a collaborationist government under German control. Up to 15,000 Norwegians volunteered to fight in German units, including the Waffen-SS.[86]

The fraction of the Norwegian population that supported Germany was traditionally smaller than in Sweden, but greater than is generally appreciated today.[[citation requise] It included a number of prominent personalities such as the Nobel-prize winning novelist Knut Hamsun. The concept of a "Germanic Union" of member states fit well into their thoroughly nationalist-patriotic ideology.

Many Norwegians and persons of Norwegian descent joined the Allied forces as well as the Free Norwegian Forces. In June 1940, a small group had left Norway following their king to Britain. This group included 13 ships, five aircraft, and 500 men from the Royal Norwegian Navy. By the end of the war, the force had grown to 58 ships and 7,500 men in service in the Royal Norwegian Navy, 5 squadrons of aircraft (including Spitfires, Sunderland flying boats and Mosquitos) in the newly formed Norwegian Air Force, and land forces including the Norwegian Independent Company 1 and 5 Troop as well as No. 10 Commandos.[[citation requise]

During the five years of German occupation, Norwegians built a resistance movement which fought the German occupation forces with both civil disobedience and armed resistance including the destruction of Norsk Hydro's heavy water plant and stockpile of heavy water at Vemork, which crippled the German nuclear programme (see: Norwegian heavy water sabotage). More important to the Allied war effort, however, was the role of the Norwegian Merchant Marine. At the time of the invasion, Norway had the fourth-largest merchant marine fleet in the world. It was led by the Norwegian shipping company Nortraship under the Allies throughout the war and took part in every war operation from the evacuation of Dunkirk to the Normandy landings. Each December Norway gives a Christmas tree to the United Kingdom as thanks for the British assistance during the Second World War. A ceremony takes place to erect the tree in London's Trafalgar Square.[87] Svalbard was not occupied by German troops. Germany secretly established a meteorological station in 1944. The crew was stuck after the general capitulation in May 1945 and were rescued by a Norwegian seal hunter on 4 September. They surrendered to the seal hunter as the last German soldiers to surrender in WW2.[88]

Post-World War II history

From 1945 to 1962, the Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament. The government, led by prime minister Einar Gerhardsen, embarked on a program inspired by Keynesian economics, emphasising state financed industrialisation and co-operation between trade unions and employers' organisations. Many measures of state control of the economy imposed during the war were continued, although the rationing of dairy products was lifted in 1949, while price control and rationing of housing and cars continued as long as until 1960.

The wartime alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States was continued in the post-war years. Although pursuing the goal of a socialist economy, the Labour Party distanced itself from the Communists (especially after the Communists' seizure of power in Czechoslovakia in 1948), and strengthened its foreign policy and defence policy ties with the US. Norway received Marshall Plan aid from the United States starting in 1947, joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OEEC) one year later, and became a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949.

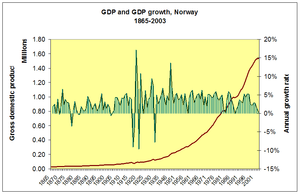

The first oil was discovered at the small Balder field in 1967, production only began in 1999.[89] In 1969, the Phillips Petroleum Company discovered petroleum resources at the Ekofisk field west of Norway. In 1973, the Norwegian government founded the State oil company, Statoil. Oil production did not provide net income until the early 1980s because of the large capital investment that was required to establish the country's petroleum industry. Around 1975, both the proportion and absolute number of workers in industry peaked. Since then labour-intensive industries and services like factory mass production and shipping have largely been outsourced.

Norway was a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway was twice invited to join the European Union, but ultimately declined to join after referendums that failed by narrow margins in 1972 and 1994.[90]

In 1981, a Conservative government led by Kåre Willoch replaced the Labour Party with a policy of stimulating the stagflated economy with tax cuts, economic liberalisation, deregulation of markets, and measures to curb record-high inflation (13.6% in 1981).

Norway's first female prime minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland of the Labour party, continued many of the reforms of her conservative predecessor, while backing traditional Labour concerns such as social security, high taxes, the industrialisation of nature, and feminism. By the late 1990s, Norway had paid off its foreign debt and had started accumulating a sovereign wealth fund. Since the 1990s, a divisive question in politics has been how much of the income from petroleum production the government should spend, and how much it should save.

In 2011, Norway suffered two terrorist attacks on the same day conducted by Anders Behring Breivik which struck the government quarter in Oslo and a summer camp of the Labour party's youth movement at Utøya island, resulting in 77 deaths and 319 wounded.

The 2013 Norwegian parliamentary election brought a more conservative government to power, with the Conservative Party and the Progress Party winning 43% of the electorate's votes.

La géographie

Norway's core territory comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula; the remote island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard are also part of the Kingdom of Norway.[note 2] The Antarctic Peter I Island and the sub-Antarctic Bouvet Island are dependent territories and thus not considered part of the Kingdom. Norway also lays claim to a section of Antarctica known as Queen Maud Land.[91] From the Middle Ages to 1814 Norway was part of the Danish kingdom. Norwegian possessions in the North Atlantic, Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland, remained Danish when Norway was passed to Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel.[92] Norway also comprised Bohuslän until 1658, Jämtland and Härjedalen until 1645,[91] Shetland and Orkney until 1468,[93] and the Hebrides and Isle of Man until the Treaty of Perth in 1266.[94]

Norway comprises the western and northernmost part of Scandinavia in Northern Europe.[95] Norway lies between latitudes 57° and 81° N, and longitudes 4° and 32° E. Norway is the northernmost of the Nordic countries and if Svalbard is included also the easternmost.[96] Vardø at 31° 10' 07" east of Greenwich lies further east than St. Petersburg and Istanbul.[97] Norway includes the northernmost point on the European mainland.[98] The rugged coastline is broken by huge fjords and thousands of islands. The coastal baseline is 2,532 kilometres (1,573 mi). The coastline of the mainland including fjords stretches 28,953 kilometres (17,991 mi), when islands are included the coastline has been estimated to 100,915 kilometres (62,706 mi).[99] Norway shares a 1,619-kilometre (1,006 mi) land border with Sweden, 727 kilometres (452 mi) with Finland, and 196 kilometres (122 mi) with Russia to the east. To the north, west and south, Norway is bordered by the Barents Sea, the Norwegian Sea, the North Sea, and Skagerrak.[100] The Scandinavian Mountains form much of the border with Sweden.

At 385,207 square kilometres (148,729 sq mi) (including Svalbard and Jan Mayen) (and 323,808 square kilometres (125,023 sq mi) without)[6], much of the country is dominated by mountainous or high terrain, with a great variety of natural features caused by prehistoric glaciers and varied topography. The most noticeable of these are the fjords: deep grooves cut into the land flooded by the sea following the end of the Ice Age. Sognefjorden is the world's second deepest fjord, and the world's longest at 204 kilometres (127 mi). Hornindalsvatnet is the deepest lake in all Europe.[101] Norway has about 400,000 lakes.[102][103] There are registred 239,057 islands.[95] Permafrost can be found all year in the higher mountain areas and in the interior of Finnmark county. Numerous glaciers are found in Norway.

The land is mostly made of hard granite and gneiss rock, but slate, sandstone, and limestone are also common, and the lowest elevations contain marine deposits. Because of the Gulf Stream and prevailing westerlies, Norway experiences higher temperatures and more precipitation than expected at such northern latitudes, especially along the coast. The mainland experiences four distinct seasons, with colder winters and less precipitation inland. The northernmost part has a mostly maritime Subarctic climate, while Svalbard has an Arctic tundra climate.

Because of the large latitudinal range of the country and the varied topography and climate, Norway has a larger number of different habitats than almost any other European country. There are approximately 60,000 species in Norway and adjacent waters (excluding bacteria and virus). The Norwegian Shelf large marine ecosystem is considered highly productive.[104]

Climat

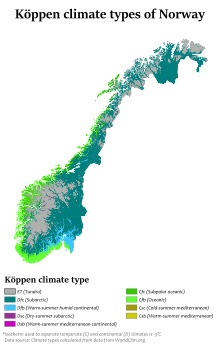

The southern and western parts of Norway, fully exposed to Atlantic storm fronts, experience more precipitation and have milder winters than the eastern and far northern parts. Areas to the east of the coastal mountains are in a rain shadow, and have lower rain and snow totals than the west. The lowlands around Oslo have the warmest and sunniest summers, but also cold weather and snow in wintertime.[107][108]

Because of Norway's high latitude, there are large seasonal variations in daylight. From late May to late July, the sun never completely descends beneath the horizon in areas north of the Arctic Circle (hence Norway's description as the "Land of the Midnight sun"), and the rest of the country experiences up to 20 hours of daylight per day. Conversely, from late November to late January, the sun never rises above the horizon in the north, and daylight hours are very short in the rest of the country.

The coastal climate of Norway is exceptionally mild compared with areas on similar latitudes elsewhere in the world, with the Gulf Stream passing directly offshore the northern areas of the Atlantic coast, continuously warming the region in the winter. Temperature anomalies found in coastal locations are exceptional, with Røst and Værøy lacking a meteorological winter in spite of being north of the Arctic Circle. The Gulf Stream has this effect only on the northern parts of Norway, not in the south, despite what is commonly believed. The northern coast of Norway would thus be ice-covered if not for the Gulf Stream.[109] As a side-effect, the Scandinavian Mountains prevent continental winds from reaching the coastline, causing very cool summers throughout Atlantic Norway. Oslo has more of a continental climate, similar to Sweden's. The mountain ranges have subarctic and tundra climates. There is also very high rainfall in areas exposed to the Atlantic, such as Bergen. Oslo, in comparison, is dry, being in a rain shadow. Skjåk in Oppland county is also in the rain shadow and is one of the driest places with 278 millimetres (10.9 inches) precipitation annually. Finnmarksvidda and the interior valleys of Troms and Nordland also receive less than 300 millimetres (12 inches) annually. Longyearbyen is the driest place in Norway with 190 millimetres (7.5 inches).[110]

Parts of southeastern Norway including parts of Mjøsa have warm-summer humid continental climates (Köppen Dfb), while the more southern and western coasts are mostly of the oceanic climate (Cfb). Further inland in southeastern and northern Norway, the subarctic climate (Dfc) dominates; this is especially true for areas in the rain shadow of the Scandinavian Mountains. Some of the inner valleys of Oppland get so little precipitation annually, thanks to the rain shadow effect, that they meet the requirements for dry-summer subarctic climates (Dsc). In higher altitudes, close to the coasts of southern and western Norway, one can find the rare subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc). This climate is also common in Northern Norway, but there usually in lower altitudes, all the way down to sea level. A small part of the northernmost coast of Norway has the tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET). Large parts of Norway are covered by mountains and high altitude plateaus, many of which also exhibit the tundra/alpine/polar climate (ET).[107][111][112][108][113]

| Climate data for Oslo-Blindern (Köppen Dfb) (1961–1990), Norway | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | Apr | Peut | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | oct | Nov | Dec | Année |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

32.2 (90.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

34.2 (93.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3,5 (38.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.6 (49.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4,5 (40.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

0,7 (33.3) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

5.7 (42.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.8 (19.8) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.3 (−11.7) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−2 (28) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−16 (3) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49 (1.9) |

36 (1.4) |

47 (1.9) |

41 (1.6) |

53 (2.1) |

65 (2.6) |

81 (3.2) |

89 (3.5) |

90 (3.5) |

84 (3.3) |

73 (2.9) |

55 (2.2) |

763 (30.1) |

| Average precipitation days | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40 | 76 | 126 | 178 | 220 | 250 | 246 | 216 | 144 | 86 | 51 | 35 | 1,668 |

| Source #1: Norwegian Meteorological Institute eklima.met.no | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Met.no[114] (precipitation > 3 mm) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Bergen (Köppen Cfb), 1961–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | Apr | Peut | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | oct | Nov | Dec | Année |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.9 (85.8) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

17,9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

11.8 (53.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2,7 (36.9) |

8.4 (47.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

5.7 (42.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.3 (2.7) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2,5 (36.5) |

2,5 (36.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−10 (14) |

−13 (9) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 190 (7.5) |

152 (6.0) |

170 (6.7) |

114 (4.5) |

106 (4.2) |

132 (5.2) |

148 (5.8) |

190 (7.5) |

283 (11.1) |

271 (10.7) |

259 (10.2) |

235 (9.3) |

2,250 (88.7) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 20 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 21 | 202 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 19 | 56 | 94 | 147 | 186 | 189 | 167 | 144 | 86 | 60 | 27 | 12 | 1,187 |

| Source #1: http://sharki.oslo.dnmi.no/pls/portal/BATCH_ORDER.PORTLET_UTIL.Download_BLob?p_BatchId=666089&p_IntervalId=1351224(eklima.no) (high and low temperatures),[115] NOAA (all else, except extremes)[116] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Voodoo Skies for extremes[117] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Brønnøysund (Köppen Cfc), 1960–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | Apr | Peut | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | oct | Nov | Dec | Année |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

0,9 (33.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 138 (5.4) |

102 (4.0) |

114 (4.5) |

97 (3.8) |

66 (2.6) |

83 (3.3) |

123 (4.8) |

113 (4.4) |

180 (7.1) |

192 (7.6) |

145 (5.7) |

157 (6.2) |

1,510 (59.4) |

| Source: Meteorologisk Institutt[114] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Rena-Haugedalen (Köppen Dfc) (1961–1990), Norway | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | Apr | Peut | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | oct | Nov | Dec | Année |

| Average high °C (°F) | −7.1 (19.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−1 (30) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

7.3 (45.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −11.2 (11.8) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

1,7 (35.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2,9 (37.2) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

1,9 (35.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−4 (25) |

1,0 (33.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2,9 (37.2) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50 (2.0) |

38 (1.5) |

40 (1.6) |

42 (1.7) |

62 (2.4) |

78 (3.1) |

90 (3.5) |

79 (3.1) |

85 (3.3) |

80 (3.1) |

67 (2.6) |

55 (2.2) |

766 (30.1) |

| La source: [118] | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity

The total number of species include 16,000 species of insects (probably 4,000 more species yet to be described), 20,000 species of algae, 1,800 species of lichen, 1,050 species of mosses, 2,800 species of vascular plants, up to 7,000 species of fungi, 450 species of birds (250 species nesting in Norway), 90 species of mammals, 45 fresh-water species of fish, 150 salt-water species of fish, 1,000 species of fresh-water invertebrates, and 3,500 species of salt-water invertebrates.[119] About 40,000 of these species have been described by science. The red list of 2010 encompasses 4,599 species.[120]

Seventeen species are listed mainly because they are endangered on a global scale, such as the European beaver, even if the population in Norway is not seen as endangered. The number of threatened and near-threatened species equals to 3,682; it includes 418 fungi species, many of which are closely associated with the small remaining areas of old-growth forests,[121] 36 bird species, and 16 species of mammals. In 2010, 2,398 species were listed as endangered or vulnerable; of these were 1250 listed as vulnerable (VU), 871 as endangered (EN), and 276 species as critically endangered (CR), among which were the grey wolf, the Arctic fox (healthy population on Svalbard) and the pool frog.[120]

The largest predator in Norwegian waters is the sperm whale, and the largest fish is the basking shark. The largest predator on land is the polar bear, while the brown bear is the largest predator on the Norwegian mainland. The largest land animal on the mainland is the elk (American English: moose). The elk in Norway is known for its size and strength and is often called skogens konge, "king of the forest".

Environnement

Attractive and dramatic scenery and landscape are found throughout Norway.[122] The west coast of southern Norway and the coast of northern Norway present some of the most visually impressive coastal sceneries in the world. National Geographic has listed the Norwegian fjords as the world's top tourist attraction.[123] The country is also home to the natural phenomena of the Midnight sun (during summer), as well as the Aurora borealis known also as the Northern lights.[124]

The 2016 Environmental Performance Index from Yale University, Columbia University and the World Economic Forum put Norway in seventeenth place, immediately below Croatia and Switzerland.[125] The index is based on environmental risks to human health, habitat loss, and changes in CO2 emissions. The index notes over-exploitation of fisheries, but not Norway's whaling or oil exports.[126]

Politics and government

Norway is considered to be one of the most developed democracies and states of justice in the world. From 1814, c. 45% of men (25 years and older) had the right to vote, whereas the United Kingdom had c. 20% (1832), Sweden c. 5% (1866), and Belgium c. 1.15% (1840). Since 2010, Norway has been classified as the world's most democratic country by the Democracy Index.[127][128][129]

According to the Constitution of Norway, which was adopted on 17 May 1814[130] and inspired by the United States Declaration of Independence and French Revolution of 1776 and 1789, respectively, Norway is a unitary constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government, wherein the King of Norway is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. Power is separated among the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government, as defined by the Constitution, which serves as the country's supreme legal document.

The monarch officially retains executive power. But following the introduction of a parliamentary system of government, the duties of the monarch have since become strictly representative and ceremonial,[131] such as the formal appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister and other ministers in the executive government. Accordingly, the Monarch is commander-in-chief of the Norwegian Armed Forces, and serves as chief diplomatic official abroad and as a symbol of unity. Harald V of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg was crowned King of Norway in 1991, the first since the 14th century who has been born in the country.[132] Haakon, Crown Prince of Norway, is the legal and rightful heir to the throne and the Kingdom.

In practice, the Prime Minister exercises the executive powers. Constitutionally, legislative power is vested with both the government and the Parliament of Norway, but the latter is the supreme legislature and a unicameral body.[133] Norway is fundamentally structured as a representative democracy. The Parliament can pass a law by simple majority of the 169 representatives, who are elected on the basis of proportional representation from 19 constituencies for four-year terms.

150 are elected directly from the 19 constituencies, and an additional 19 seats ("levelling seats") are allocated on a nationwide basis to make the representation in parliament correspond better with the popular vote for the political parties. A 4% election threshold is required for a party to gain levelling seats in Parliament.[134] There are a total of 169 members of parliament.

The Parliament of Norway, called the Stortinget (meaning Grand Assembly), ratifies national treaties developed by the executive branch. It can impeach members of the government if their acts are declared unconstitutional. If an indicted suspect is impeached, Parliament has the power to remove the person from office.

The position of prime minister, Norway's head of government, is allocated to the member of Parliament who can obtain the confidence of a majority in Parliament, usually the current leader of the largest political party or, more effectively, through a coalition of parties. A single party generally does not have sufficient political power in terms of the number of seats to form a government on its own. Norway has often been ruled by minority governments.

The prime minister nominates the cabinet, traditionally drawn from members of the same political party or parties in the Storting, making up the government. The PM organises the executive government and exercises its power as vested by the Constitution.[135] Norway has a state church, the Lutheran Church of Norway, which has in recent years gradually been granted more internal autonomy in day-to-day affairs, but which still has a special constitutional status. Formerly, the PM had to have more than half the members of cabinet be members of the Church of Norway, meaning at least ten out of the 19 ministries. This rule was however removed in 2012. The issue of separation of church and state in Norway has been increasingly controversial, as many people believe it is time to change this, to reflect the growing diversity in the population. A part of this is the evolution of the public school subject Christianity, a required subject since 1739. Even the state's loss in a battle at the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg[136] in 2007 did not settle the matter. As of 1 January 2017, the Church of Norway is a separate legal entity, and no longer a branch of the civil service.[137]

Through the Council of State, a privy council presided over by the monarch, the prime minister and the cabinet meet at the Royal Palace and formally consult the Monarch. All government bills need the formal approval by the monarch before and after introduction to Parliament. The Council reviews and approves all of the monarch's actions as head of state. Although all government and parliamentary acts are decided beforehand, the privy council is an example of symbolic gesture the king retains.[132]

Members of the Storting are directly elected from party-lists proportional representation in nineteen plural-member constituencies in a national multi-party system.[138] Historically, both the Norwegian Labour Party and Conservative Party have played leading political roles. In the early 21st century, the Labour Party has been in power since the 2005 election, in a Red–Green Coalition with the Socialist Left Party and the Centre Party.[139]

Since 2005, both the Conservative Party and the Progress Party have won numerous seats in the Parliament, but not sufficient in the 2009 general election to overthrow the coalition. Commentators have pointed to the poor co-operation between the opposition parties, including the Liberals and the Christian Democrats. Jens Stoltenberg, the leader of the Labour Party, continued to have the necessary majority through his multi-party alliance to continue as PM until 2013.[140]

In national elections in September 2013, voters ended eight years of Labor rule. Two political parties, Høyre and Fremskrittspartiet, elected on promises of tax cuts, more spending on infrastructure and education, better services and stricter rules on immigration, formed a government. Coming at a time when Norway's economy is in good condition with low unemployment, the rise of the right appeared to be based on other issues. Erna Solberg became prime minister, the second female prime minister after Brundtland and the first conservative prime minister since Syse. Solberg said her win was "a historic election victory for the right-wing parties".[141]

divisions administratives

Norway, a unitary state, is divided into eighteen first-level administrative counties (fylke). The counties are administrated through directly elected county assemblies who elect the County Governor. Additionally, the King and government are represented in every county by a fylkesmann, who effectively acts as a Governor.[142] As such, the Government is directly represented at a local level through the County Governors' offices. The counties are then sub-divided into 422-second-level municipalities (kommuner), which in turn are administrated by directly elected municipal council, headed by a mayor and a small executive cabinet. The capital of Oslo is considered both a county and a municipality.

Norway has two integral overseas territories: Jan Mayen and Svalbard, the only developed island in the archipelago of the same name, located miles away to the north. There are three Antarctic and Subantarctic dependencies: Bouvet Island, Peter I Island, and Queen Maud Land. On most maps, there had been an unclaimed area between Queen Maud Land and the South Pole until 12 June 2015 when Norway formally annexed that area.[143]

96 settlements have city status in Norway. In most cases, the city borders are coterminous with the borders of their respective municipalities. Often, Norwegian city municipalities include large areas that are not developed; for example, Oslo municipality contains large forests, located north and south-east of the city, and over half of Bergen municipality consists of mountainous areas.

The counties of Norway are:

Largest cities

|

Largest cities or towns in Norway

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rang | prénom | Comté | Pop. | Rang | prénom | Comté | Pop. | |||||||||

Bergen |

1 | Oslo | Oslo | 1,000,467 | 11 | Moss | Østfold | 46,618 |  Stavanger/Sandnes |

Bergen | Hordaland | 255,464 | 12 | Haugesund | Rogaland | 44,830 |

| 3 | Stavanger/Sandnes | Rogaland | 222,697 | 13 | Sandefjord | Vestfold | 43,595 | |||||||||

| 4 | Trondheim | Trøndelag | 183,378 | 14 | Arendal | Aust-Agder | 43,084 | |||||||||

| 5 | Drammen | Buskerud | 117,510 | 15 | Bodø | Nordland | 40,705 | |||||||||

| 6 | Fredrikstad/Sarpsborg | Østfold | 111,267 | 16 | Tromsø | Troms | 38,980 | |||||||||

| 7 | Porsgrunn/Skien | Telemark | 92,753 | 17 | Hamar | Hedmark | 27,324 | |||||||||

| 8 | Kristiansand | Vest-Agder | 61,536 | 18 | Halden | Østfold | 25,300 | |||||||||

| 9 | Ålesund | Møre og Romsdal | 52,163 | 19 | Larvik | Vestfold | 24,208 | |||||||||

| dix | Tønsberg | Vestfold | 51,571 | 20 | Askøy | Hordaland | 23,194 | |||||||||

Judicial system and law enforcement

Norway uses a civil law system where laws are created and amended in Parliament and the system regulated through the Courts of justice of Norway. It consists of the Supreme Court of 20 permanent judges and a Chief Justice, appellate courts, city and district courts, and conciliation councils.[144] The judiciary is independent of executive and legislative branches. While the Prime Minister nominates Supreme Court Justices for office, their nomination must be approved by Parliament and formally confirmed by the Monarch in the Council of State. Usually, judges attached to regular courts are formally appointed by the Monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The Courts' strict and formal mission is to regulate the Norwegian judicial system, interpret the Constitution, and as such implement the legislation adopted by Parliament. In its judicial reviews, it monitors the legislative and executive branches to ensure that they comply with provisions of enacted legislation.[144]

The law is enforced in Norway by the Norwegian Police Service. It is a Unified National Police Service made up of 27 Police Districts and several specialist agencies, such as Norwegian National Authority for the Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime, known as Økokrim; and the National Criminal Investigation Service, known as Kripos, each headed by a chief of police. The Police Service is headed by the National Police Directorate, which reports to the Ministry of Justice and the Police. The Police Directorate is headed by a National Police Commissioner. The only exception is the Norwegian Police Security Agency, whose head answers directly to the Ministry of Justice and the Police.

Norway abolished the death penalty for regular criminal acts in 1902. The legislature abolished the death penalty for high treason in war and war-crimes in 1979. Reporters Without Borders, in its 2007 Worldwide Press Freedom Index, ranked Norway at a shared first place (along with Iceland) out of 169 countries.[145]

In general, the legal and institutional framework in Norway is characterised by a high degree of transparency, accountability and integrity, and the perception and the occurrence of corruption are very low.[146] Norway has ratified all relevant international anti-corruption conventions, and its standards of implementation and enforcement of anti-corruption legislation are considered very high by many international anti-corruption working groups such as the OECD Anti-Bribery Working Group. However, there are some isolated cases showing that some municipalities have abused their position in public procurement processes.

Norwegian prisons are humane, rather than tough, with emphasis on rehabilitation. At 20%, Norway's re-conviction rate is among the lowest in the world.[147]

Foreign relations, including with European Union

Norway maintains embassies in 82 countries.[148] 60 countries maintain an embassy in Norway, all of them in the capital, Oslo.

Norway is a founding member of the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Council of Europe and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Norway issued applications for accession to the European Union (EU) and its predecessors in 1962, 1967 and 1992, respectively. While Denmark, Sweden and Finland obtained membership, the Norwegian electorate rejected the treaties of accession in referenda in 1972 and 1994.

After the 1994 referendum, Norway maintained its membership in the European Economic Area (EEA), an arrangement granting the country access to the internal market of the Union, on the condition that Norway implements the Union's pieces of legislation which are deemed relevant (of which there were approximately seven thousand by 2010)[149] Successive Norwegian governments have, since 1994, requested participation in parts of the EU's co-operation that go beyond the provisions of the EEA agreement. Non-voting participation by Norway has been granted in, for instance, the Union's Common Security and Defence Policy, the Schengen Agreement, and the European Defence Agency, as well as 19 separate programmes.[150]

Norway participated in the 1990s brokering of the Oslo Accords, an unsuccessful attempt to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Militaire

The Norwegian Armed Forces numbers about 25,000 personnel, including civilian employees. According to 2009 mobilisation plans, full mobilisation produces approximately 83,000 combatant personnel. Norway has conscription (including 6–12 months of training);[151] in 2013, the country became the first in Europe and NATO to draft women as well as men. However, due to less need for conscripts after the Cold War ended with the break-up of the Soviet Union, few people have to serve if they are not motivated.[152] The Armed Forces are subordinate to the Norwegian Ministry of Defence. The Commander-in-Chief is King Harald V. The military of Norway is divided into the following branches: the Norwegian Army, the Royal Norwegian Navy, the Royal Norwegian Air Force, the Norwegian Cyber Defence Force and the Home Guard.

In response to its being overrun by Germany in 1940, the country was one of the founding nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949. At present, Norway contributes in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan.[153] Additionally, Norway has contributed in several missions in contexts of the United Nations, NATO, and the Common Security and Defence Policy of the European Union.

Économie

Norwegians enjoy the second-highest GDP per-capita among European countries (after Luxembourg), and the sixth-highest GDP (PPP) per-capita in the world. Today, Norway ranks as the second-wealthiest country in the world in monetary value, with the largest capital reserve per capita of any nation.[154] According to the CIA World Factbook, Norway is a net external creditor of debt.[100] Norway maintained first place in the world in the UNDP Human Development Index (HDI) for six consecutive years (2001–2006),[10] and then reclaimed this position in 2009, through 2015.[21] The standard of living in Norway is among the highest in the world. Foreign Policy magazine ranks Norway last in its Failed States Index for 2009, judging Norway to be the world's most well-functioning and stable country. The OECD ranks Norway fourth in the 2013 equalised Better Life Index and third in intergenerational earnings elasticity.[155][156]

The Norwegian economy is an example of a mixed economy, a prosperous capitalist welfare state and social democracy country featuring a combination of free market activity and large state ownership in certain key sectors. Public health care in Norway is free (after an annual charge of around 2000 kroner for those over 16), and parents have 46 weeks paid[157] parental leave. The state income derived from natural resources includes a significant contribution from petroleum production. Norway has an unemployment rate of 4.8%, with 68% of the population aged 15–74 employed.[158] People in the labour force are either employed or looking for work.[159] 9.5% of the population aged 18–66 receive a disability pension[160] and 30% of the labour force are employed by the government, the highest in the OECD.[161] The hourly productivity levels, as well as average hourly wages in Norway, are among the highest in the world.[162][163]

The egalitarian values of Norwegian society have kept the wage difference between the lowest paid worker and the CEO of most companies as much less than in comparable western economies.[164] This is also evident in Norway's low Gini coefficient.