Denver – Wikipedia

capitale de l'État du Colorado, États-Unis; ville et comté consolidés

Capitale de l'État et ville-comté consolidée du Colorado

|

Denver, Colorado |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ville et comté de Denver | |||

| Surnoms: | |||

Configuration ville / comté |

|||

| Coordonnées: 39 ° 45′43 ″ N 104 ° 52′52 ″ W/39,761850 ° N 104,881105 ° WCoordonnées: 39 ° 45′43 ″ N 104 ° 52′52 ″ W/39,761850 ° N 104,881105 ° W[5] | |||

| Pays | |||

| Etat | |||

| Ville et comté | Denver[1] | ||

| Fondé | 17 novembre 1858, sous le nom de Denver City, K.T.[6] | ||

| Incorporé | 7 novembre 1861, sous le nom de Denver City, C.T.[7] | ||

| Consolidée | 1er décembre 1902, en tant que ville et comté de Denver[8][9] | ||

| Nommé pour | James W. Denver | ||

| Gouvernement | |||

| • Type | Ville et comté consolidés[1] | ||

| • corps | Mairie de Denver | ||

| • maire | Michael Hancock (D)[10] | ||

| Zone | |||

| • Capitale de l’État et ville-comté consolidée | 154 km (401,36 km)2) | ||

| • Terre | 153,337 mi (397,13 km2) | ||

| • L'eau | 1,23 km2) 1,1% | ||

| • métro | 21 793 km2) | ||

| Élévation | 5 130 à 5 690 pieds (1 564 à 1 734 m) | ||

| Population | |||

| • Capitale de l’État et ville-comté consolidée | 600 158 | ||

| • Estimation | 716 492 | ||

| • Rang | US: 19ème | ||

| • Densité | 1 745,15 / km2) | ||

| • Urbain | 2.374.203 (US: 18ème) | ||

| • métro | 2 932 415 (US: 19ème) | ||

| • CSA | 3,572,798 (US: 15ème) | ||

| Demonym (s) | Denverite | ||

| Fuseau horaire | UTC-7 (MST) | ||

| • été (heure d'été) | UTC-6 (MDT) | ||

| codes ZIP |

80201–80212, 80214–80239, 80241, 80243–80244, 80246–80252, 80256–80266, 80271, 80273–80274, 80279–80281, 80290–80291, 80293–80295, 80293–80295, 80299, 8002, 80014, 80014, 8002, 80299. 80123, 80127[16]

|

||

| Indicatif régional | 303 et 720 | ||

| Code FIPS | 08-20000 | ||

| ID de fonctionnalité GNIS | 0201738 | ||

| Aéroport majeur | Aéroport international de Denver | ||

| Interstates | |||

| Routes américaines | |||

| Autoroutes | Train de banlieue | UNE B g | |

| Transit rapide | C ré E F H L R W | ||

| Site Internet | denvergov.org | ||

|

Capitale et ville la plus peuplée de la État du Colorado |

|||

Denver (), officiellement le Ville et comté de Denver, est la capitale et la municipalité la plus peuplée de l’état américain du Colorado. Denver est situé dans la vallée de la rivière South Platte, à l’ouest des Hautes Plaines, juste à l’est de la chaîne de montagnes Front des montagnes Rocheuses. Le centre-ville de Denver se trouve immédiatement à l'est du confluent de Cherry Creek et de la rivière South Platte, à environ 19 km à l'est des contreforts des montagnes Rocheuses. Denver doit son nom à James W. Denver, gouverneur du territoire du Kansas. Il est surnommé le Mile High City parce que son altitude officielle est exactement un mile (5280 pieds ou 1609.3 mètres) au dessus du niveau de la mer.[17] Le 105e méridien situé à l'ouest de Greenwich, la référence longitudinale pour le fuseau horaire des Rocheuses, passe directement par la gare Union de Denver.

Denver est classée comme ville mondiale bêta par le réseau de recherche sur la mondialisation et les villes du monde. Avec une population estimée à 716 492 habitants en 2018, Denver est la 19e ville la plus peuplée des États-Unis et, avec une augmentation de 19,38% depuis le recensement des États-Unis de 2010, elle compte parmi les grandes villes à la croissance la plus rapide aux États-Unis.[18] La région métropolitaine de statistiques de Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO, avait une population estimée à 2 932 415 habitants en 2018 et constitue la 19e région métropolitaine de statistique la plus peuplée des États-Unis.[19] La région statistique combinée de 12 villes de Denver-Aurora, CO, avait une population estimée à 3 572 798 personnes en 2018 et constitue la 15e région métropolitaine la plus peuplée des États-Unis.[20] Denver est la ville la plus peuplée du couloir urbain Front Range, composé de 18 comtés, une zone urbaine oblongue qui s'étend sur deux États et qui compte une population estimée à 4 976 781 habitants en 2018.[21] Denver est la ville la plus peuplée dans un rayon de 800 km (800 km) et la deuxième ville la plus peuplée de Mountain West après Phoenix, en Arizona. En 2016, Denver a été nommé le meilleur endroit où vivre aux États-Unis par Nouvelles américaines et rapport mondial.[22]

Histoire[[modifier]

À l'été de 1858, pendant la ruée vers l'or du pic de Pike, un groupe de prospecteurs d'or de Lawrence, au Kansas, fonda Montana City en tant que ville minière sur les rives de la rivière South Platte, dans l'ancien territoire du Kansas. Ce fut le premier établissement historique dans ce qui deviendra plus tard la ville de Denver. Cependant, le site s'effaça rapidement et, à l'été de 1859, il fut abandonné au profit d'Auraria (nommée d'après la ville aurifère Auraria, Géorgie) et de la ville de Saint-Charles.[23]

Le 22 novembre 1858, le général William Larimer et le capitaine Jonathan Cox, Esquire, deux spéculateurs terriens de l'est du territoire du Kansas, placèrent des bûches de peuplier dans le but de revendiquer le droit le site minier existant d’Auraria et sur le site de la ville existante de Saint-Charles. Larimer a nommé le lotissement urbain de Denver City pour s'attirer les faveurs du gouverneur du Kansas, James W. Denver.[24] Larimer espérait que le nom de la ville l'aiderait à devenir le siège du comté d'Arapaho mais, à son insu, le gouverneur Denver avait déjà démissionné de ses fonctions. L'emplacement était accessible aux sentiers existants et était situé de l'autre côté de la rivière South Platte à partir des campements saisonniers de Cheyenne et d'Arapaho. Le site de ces premières villes est maintenant occupé par le parc Confluence, situé près du centre-ville de Denver.

Larimer, avec des associés de la St. Charles City Land Company, a vendu des colis dans la ville à des marchands et à des mineurs, dans le but de créer une grande ville pouvant accueillir de nouveaux immigrants. La ville de Denver était une ville frontière, avec une économie basée sur le service des mineurs locaux avec le jeu, les salons, le bétail et le commerce de marchandises. Dans les premières années, les parcelles de terrain étaient souvent échangées contre des participations minimes ou mises en jeu par des mineurs à Auraria.[24] En mai 1859, les habitants de Denver City firent don de 53 lots au Leavenworth & Pike's Peak Express afin de sécuriser le premier itinéraire de wagon de terre de la région. Offrant un service quotidien pour "les passagers, le courrier, le fret et l'or", l'Express a atteint Denver par un sentier qui réduisait la durée du trajet vers l'ouest de douze à six jours. En 1863, Western Union renforça la domination de Denver sur la région en choisissant la ville pour son terminus régional.

Le territoire du Colorado a été créé le 28 février 1861.[25] Le comté d’Arapahoe a été formé le 1 er novembre 1861,[25] et Denver City a été constituée le 7 novembre 1861.[26] La ville de Denver servit de siège du comté d’Arapahoe de 1861 à 1902, date de sa consolidation.[27] En 1867, Denver City devint la capitale territoriale par intérim et, en 1881, elle fut choisie comme capitale permanente de l'État par un vote à l'échelle de l'État. Avec sa nouvelle importance, Denver City a raccourci son nom à Denver.[27] Le 1 er août 1876, le Colorado est admis dans l’Union.

Même si, à la fin des années 1860, les habitants de Denver pouvaient être fiers d’avoir réussi à établir un centre d’approvisionnement et de services dynamique, la décision de faire passer le premier chemin de fer transcontinental du pays par Cheyenne plutôt que Denver menaçait la prospérité de la jeune ville. Le chemin de fer transcontinental a dépassé 100 kilomètres, mais les citoyens se sont mobilisés pour construire un chemin de fer reliant Denver à celui-ci. La levée de fonds a été lancée par des leaders visionnaires, dont le gouverneur de la région, John Evans, David Moffat et Walter Cheesman. En trois jours, 300 000 $ avaient été collectés et les citoyens étaient optimistes. La collecte de fonds a stagné avant que suffisamment d’argent soit réuni, forçant ces dirigeants visionnaires à prendre le contrôle du chemin de fer endetté par la dette. Malgré les difficultés, le 24 juin 1870, les citoyens se réjouirent de l’achèvement du lien entre le Denver Pacific et le chemin de fer transcontinental, ouvrant ainsi une nouvelle ère de prospérité à Denver.[28]

Enfin reliée au reste du pays par le rail, Denver a prospéré en tant que centre de services et d’approvisionnement. La jeune ville s'est développée au cours de ces années, attirant des millionnaires avec leurs hôtels particuliers, ainsi qu'un mélange de criminalité et de pauvreté dans une ville en pleine croissance. Les citoyens de Denver étaient fiers lorsque les riches ont choisi Denver et ont été ravis lorsque Horace Tabor, le millionnaire des mines à Leadville, a construit un impressionnant bloc d’affaires à 16th et Larimer, ainsi que l’élégant Tabor Grand Opera House. Des hôtels de luxe, dont le très apprécié Brown Palace Hotel, ont rapidement suivi, ainsi que de splendides demeures pour des millionnaires, telles que Croke, Patterson, Campbell Mansion à 11th et Pennsylvania et le Moffat Mansion, aujourd'hui démoli, à 8th and Grant.[29] Désireux de transformer Denver en l'une des plus grandes villes du monde, les dirigeants ont séduit l'industrie et attiré des ouvriers dans ces usines.

Bientôt, outre l'élite et une classe moyenne nombreuse, Denver comptait une population croissante d'immigrants allemands, italiens et chinois, bientôt suivis par des Afro-Américains du Deep South et des travailleurs hispaniques. L'afflux de nouveaux résidents a mis à rude épreuve les logements disponibles. En outre, le Silver Crash de 1893 a perturbé les équilibres politiques, sociaux et économiques. La compétition entre les différents groupes ethniques a souvent été qualifiée de bigoterie et les tensions sociales ont donné lieu à la peur rouge. Les Américains se méfiaient des immigrants parfois associés à des causes socialistes et syndicales. Après la Première Guerre mondiale, une renaissance du Ku Klux Klan a attiré des Américains blancs nés dans le pays, inquiets des nombreux changements survenus dans la société. Contrairement aux organisations précédentes actives dans les régions rurales du Sud, les sections de KKK se sont développées dans les zones urbaines du Midwest et de l’Ouest, y compris Denver, ainsi que dans l’Idaho et l’Oregon. La corruption et le crime se sont également développés à Denver.[30]

Entre 1880 et 1895, la ville connut une énorme augmentation de la corruption, alors que des patrons du crime, tels que Soapy Smith, travaillaient côte à côte avec les élus et la police pour contrôler les élections, les jeux de hasard et les gangs de bunco.[31] La ville subit également une dépression en 1893 après la chute des prix de l'argent. En 1887, le précurseur de l'organisation caritative internationale United Way a été formé à Denver par des chefs religieux locaux, qui ont collecté des fonds et coordonné diverses organisations caritatives pour aider les pauvres de Denver.[32] En 1890, Denver était devenue la deuxième ville en importance à l'ouest d'Omaha, dans le Nebraska.[33] En 1900, les Blancs représentaient 96,8% de la population de Denver.[34] Les populations afro-américaines et hispaniques ont augmenté avec les migrations du 20ème siècle. De nombreux Afro-Américains sont d'abord venus travailler sur le chemin de fer, qui avait un terminus à Denver, et ont commencé à s'y installer.

Entre les années 1880 et les années 1930, l’industrie floricole de Denver s’est développée et a prospéré.[35][36] Cette période est connue localement sous le nom de ruée vers l'or des œillets.[37]

Un projet de loi proposant un amendement constitutionnel de l’État autorisant l’autonomie de Denver et d’autres municipalités a été présenté à la législature en 1901 et adopté. La mesure prévoyait un référendum à l'échelle de l'État, que les électeurs ont approuvé en 1902. Le 1er décembre de cette année, le gouverneur James Orman a proclamé que la modification faisait partie de la loi fondamentale de l'État. La ville et le comté de Denver ont été créés à cette date et ont été séparés des comtés d'Arapahoe et Adams.[8][9][38]

Au début du XXe siècle, Denver, comme de nombreuses autres villes, abritait une société automobile pionnière, Brass Era. La société automobile Colburn a fabriqué des voitures copiées à partir de l'un de ses contemporains, Renault.[39]

De 1953 à 1989, l’usine de Rocky Flats, une installation d’armes nucléaires du DOE située à environ 15 km de Denver, produisait des "fosses" de plutonium fissiles pour les ogives nucléaires. Un important incendie survenu en 1957 ainsi que des fuites de déchets nucléaires entreposés sur le site entre 1958 et 1968 ont entraîné la contamination de certaines parties de Denver, à des degrés divers, avec du plutonium 239, une substance radioactive nocive demi-vie de 24 200 ans.[40] Le Dr Carl Johnson, directeur des services de santé du comté de Jefferson, a réalisé en 1981 une étude reliant la contamination à une augmentation des anomalies congénitales et de l'incidence du cancer dans le centre de Denver et à proximité de Rocky Flats. Des études ultérieures ont confirmé plusieurs de ses découvertes.[41][42][43] La contamination par le plutonium était toujours présente à l'extérieur de l'ancien site de l'usine en août 2010.[update].[44] Il présente des risques pour la construction de la promenade prévue Jefferson,[45] qui compléterait le périphérique automobile de Denver.

En 1970, Denver a été choisi pour accueillir les Jeux olympiques d’hiver de 1976, à l’occasion des célébrations du centenaire du Colorado, mais en novembre 1972, les électeurs du Colorado ont annulé les initiatives de vote qui allouaient des fonds publics aux coûts élevés des jeux. Ils ont été transférés à Innsbruck, en Autriche.[46] La notoriété de devenir la seule ville à avoir jamais refusé d'organiser une olympiade après avoir été sélectionnée a rendu difficiles les candidatures suivantes. Le mouvement contre l'organisation de jeux était basé en grande partie sur des questions environnementales et était dirigé par le représentant de l'État, Richard Lamm. Il a ensuite été élu pour trois mandats (1975-1987) au poste de gouverneur du Colorado.[47] Denver a exploré une offre potentielle pour les Jeux olympiques d'hiver de 2022,[48] mais aucune offre n'a été soumise.[49]

En 2010, Denver a adopté une mise à jour complète de son code de zonage.[50] Le nouveau zonage a été développé pour guider le développement tel que prévu dans les plans adoptés tels que Blueprint Denver,[51] Plan stratégique de développement axé sur le transport en commun, Greenprint Denver et le plan stratégique de transport.

Denver a accueilli la Convention nationale démocrate à deux reprises, en 1908 et en 2008. Elle a promu la ville sur la scène nationale, politique et socio-économique.[52] Du 10 au 15 août 1993, Denver a accueilli la 6e Journée mondiale de la jeunesse de l'Église catholique, à laquelle ont assisté environ 500 000 personnes, ce qui en fait le plus grand rassemblement de l'histoire du Colorado.

Denver a été connu historiquement comme le Reine ville des plaines et le Reine Ville de l'Ouest, en raison de son rôle important dans l’industrie agricole de la région des hautes plaines dans l’est du Colorado et le long des contreforts du Colorado Front Range. Plusieurs navires de la marine américaine ont été nommés USS Denver en l'honneur de la ville.

Géographie[[modifier]

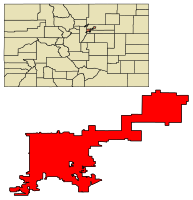

Denver est au centre du corridor urbain de Front Range, entre les montagnes Rocheuses à l'ouest et les hautes plaines à l'est. La topographie de Denver se compose de plaines dans le centre-ville avec des zones de collines au nord, à l'ouest et au sud. Selon le Bureau du recensement des États-Unis, la ville a une superficie totale de 401 km carrés (401 km2), dont 153 milles carrés (396 km2) est un terrain et 1,6 miles carrés (4,1 km2) (1,1%) est de l’eau.[53] La ville et le comté de Denver ne sont entourés que de trois autres comtés: le comté d'Adams au nord et à l'est, le comté d'Arapahoe au sud et à l'est et le comté de Jefferson à l'ouest.

Bien que le surnom de Denver soit la "Mile-High City" car son altitude officielle est d'un kilomètre au dessus du niveau de la mer, défini par l'altitude d'un point de repère sur les marches du bâtiment State Capitol, la hauteur de la ville entière est comprise entre 5 130 à 5 690 pieds (1 560 à 1 730 m). Selon le GNIS (Geographic Names Information System) et le National Elevation Dataset, la ville se situe à une altitude de 5 278 pieds (1 609 m), comme indiqué sur divers sites Web tels que le National Weather Service.[54]

Quartiers[[modifier]

En janvier 2013, la ville et le comté de Denver avaient défini 78 quartiers officiels que la ville et les groupes communautaires utilisaient pour la planification et l'administration.[55] Bien que la délimitation des limites du quartier par la ville soit quelque peu arbitraire, elle correspond en gros aux définitions utilisées par les résidents. Ces "quartiers" ne doivent pas être confondus avec des villes ou des banlieues, qui peuvent être des entités séparées dans la région métropolitaine.

Le caractère des quartiers varie considérablement d’un lieu à l’autre et comprend tout, des grands gratte-ciel aux maisons de la fin du XIXe siècle aux développements modernes de style suburbain. En règle générale, les quartiers les plus proches du centre-ville sont plus denses, plus anciens et contiennent davantage de matériaux de construction en brique. De nombreux quartiers éloignés du centre-ville ont été développés après la Seconde Guerre mondiale et sont construits avec des matériaux et un style plus modernes. Certains quartiers, même plus éloignés du centre-ville, ou des parcelles récemment réaménagées partout dans la ville, présentent des caractéristiques très suburbaines ou constituent de nouveaux développements urbanistes qui tentent de recréer l'atmosphère des quartiers plus anciens. La plupart des quartiers contiennent des parcs ou d'autres éléments qui constituent le point central du quartier.[[citation requise]

Denver n'a pas de désignation de zones plus étendues, contrairement à la ville de Chicago, qui possède des zones plus étendues abritant les quartiers (IE: Northwest Side). Les habitants de Denver utilisent les termes "nord", "sud", "est" et "ouest".[56]

Denver a également un certain nombre de quartiers non reflétés dans les limites administratives. Ces quartiers peuvent refléter la façon dont les habitants d’une zone s’identifient ou ceux d’autres, tels que les promoteurs immobiliers, qui ont défini ces zones. Les quartiers non administratifs bien connus incluent le LoDo (abréviation de "Lower Downtown"), quartier historique et branché, qui fait partie du quartier de la gare Union de la ville; Uptown, à cheval sur North Capitol Hill et City Park West; Curtis Park, une partie du quartier Five Points; Alamo Placita, la partie nord du quartier de Speer; Park Hill, un exemple réussi d’intégration raciale intentionnelle;[57] et Triangle d'Or, au centre civique.

Comtés adjacents, municipalités et lieux désignés de recensement (CDP)[[modifier]

| Nord: Comté d'Adams, Berkley, Northglenn, Commerce City | ||

| Ouest: Comté de Jefferson, Arvada, Wheat Ridge, Lakeside, Vue sur la montagne, Edgewater, Lakewood, Dakota Ridge | Denver Enclave: Comté d'Arapahoe, Glendale, Holly Hills |

Comté d'Adams Est: Aurore Comté d'Arapahoe |

| Sud: Comté d'Arapahoe, Bow Mar, Littleton, Sheridan, Englewood, Village de Cherry Hills, Village de Greenwood, Aurora |

Climat[[modifier]

Denver se situe dans la zone climatique semi-aride continentale (classification climatique de Köppen: BSk).[58] Malgré le fait que le climat est partiellement sec, les données de l’Université de Melbourne montrent que Denver est influencé par d’autres climats qui sont peut-être une conséquence de l’altitude adjacente qui modifie les précipitations et la température. On peut trouver des microclimats continentaux et subtropicaux humides.[59][60] Il a quatre saisons distinctes et reçoit la plupart de ses précipitations d'avril à août. En raison de son emplacement à l'intérieur des terres dans les Hautes Plaines, au pied des montagnes Rocheuses, la région peut être soumise à de brusques changements météorologiques.[61]

Juillet est le mois le plus chaud, avec une température moyenne de 31 ° C (88 ° F).[62] Les étés vont de chaud à chaud avec des orages occasionnels, parfois violents, l'après-midi et des températures élevées atteignant 32 ° C (38 ° C) tous les 38 jours, et occasionnellement à 38 ° C (38 ° C). Décembre, le mois le plus froid de l'année, a une température maximale moyenne quotidienne de 46 ° F (7,8 ° C). Les hivers sont constitués de périodes de neige et de températures très basses alternant avec des périodes de temps plus clément en raison de l’effet de réchauffement des vents chinook. En hiver, les maximums diurnes peuvent dépasser 16 ° C (60 ° F), mais souvent aussi ne pas atteindre 0 ° C (32 ° F) par temps froid et ne pas atteindre une température supérieure à -18 ° C (0 ° F) à l'occasion.[63] Les nuits les plus froides de l'année, les minimums peuvent facilement tomber jusqu'à -23 ° C (-10 ° F) ou moins. Les chutes de neige sont fréquentes à la fin de l'automne, en hiver et au début du printemps, atteignant en moyenne 53,5 pouces (136 cm) pour la période 1981-2010.[64] La fenêtre moyenne pour la neige mesurable (≥ 0,1 pouce ou 0,25 cm) va du 17 octobre au 27 avril; Cependant, des chutes de neige mesurables sont tombées à Denver dès le 4 septembre et jusqu'au 3 juin.[65] Les températures extrêmes varient entre -34 ° C (9 ° C) le 9 janvier 1875 et 41 ° C (105 ° F) le 29 juin 2018.[66] En raison de la forte altitude et de la sécheresse de la ville, les variations de température diurnes sont importantes toute l'année.

Les tornades sont rares à l'ouest du corridor I-25; Cependant, une exception notable est une tornade F3 qui a frappé le 15 juin 1988 à 4,4 miles au sud du centre-ville. D'autre part, la banlieue à l'est de Denver et son extension est-nord-est (aéroport international de Denver) peuvent voir quelques tornades, tornades souvent inexploitées, chaque printemps et chaque été, en particulier en juin, avec l’amélioration de la zone de tourbillon de convergence de Denver (DCVZ). La DCVZ, également connue sous le nom de cyclone de Denver, est un tourbillon variable de flux d’air formant la tempête, que l’on trouve généralement au nord et à l’est du centre-ville et qui inclut souvent l’aéroport.[67][68] Les intempéries de la DCVZ peuvent perturber les opérations de l’aéroport.[69][70] Dans une étude sur les événements de grêle dans les régions d'au moins 50 000 habitants, Denver s'est classée au 10 e rang des régions les plus exposées aux tempêtes de grêle sur le continent américain.[71] En fait, Denver a reçu le 11 juillet 1990 trois des 10 tempêtes de grêle les plus coûteuses de l'histoire des États-Unis. 20 juillet 2009; et le 8 mai 2017 respectivement.

Sur la base des moyennes sur 30 ans obtenues auprès du Centre national de données climatiques de la NOAA pour les mois de décembre, janvier et février, Weather Channel a classé Denver au 18ème rang des principales villes américaines les plus froides au monde en 2014.[update].[72]

| Données climatiques pour Denver (DIA), normales entre 1981 et 2010,[a] extrêmes 1872 − présent[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | avr | Mai | Juin | juil | Août | SEP | oct | nov | déc | Année |

| Record haut ° F (° C) | 76 (24) |

80 (27) |

84 (29) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

90 (32) |

81 (27) |

79 (26) |

105 (41) |

| Moyenne maximale ° F (° C) | 64,7 (18.2) |

66,5 (19.2) |

73,9 (23.3) |

80,8 (27.1) |

87,8 (31,0) |

95,9 (35,5) |

99,2 (37.3) |

96,4 (35,8) |

91,5 (33.1) |

82,7 (28.2) |

73,6 (23.1) |

64,9 (18.3) |

99,9 (37,7) |

| Moyenne haute ° F (° C) | 44,0 (6.7) |

46.2 (7.9) |

54,4 (12.4) |

61,5 (16.4) |

71,5 (21,9) |

82,4 (28,0) |

89,4 (31,9) |

87,2 (30,7) |

78,5 (25,8) |

65,3 (18,5) |

52,1 (11.2) |

42,8 (6.0) |

64,6 (18.1) |

| Moyenne journalière ° F (° C) | 30,7 (−0,7) |

32,5 (0,3) |

40.4 (4.7) |

47,4 (8.6) |

57,1 (13,9) |

64,7 (18.2) |

74,2 (23,4) |

72,5 (22,5) |

63,4 (17,4) |

50,9 (10.5) |

38,3 (3.5) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

50,5 (10.3) |

| Moyenne basse ° F (° C) | 17.4 (−8.1) |

18,9 (−7.3) |

26.4 (−3,1) |

33,3 (0,7) |

42,7 (5.9) |

52,3 (11.3) |

58,9 (14,9) |

57,9 (14.4) |

48,3 (9.1) |

36,6 (2.6) |

24,5 (−4.2) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

36,2 (2.3) |

| Moyenne minimale ° F (° C) | −3,0 (−19,4) |

−1.3 (−18,5) |

10.4 (−12.0) |

19,7 (−6,8) |

31.0 (−0,6) |

41,6 (5.3) |

50,9 (10.5) |

49,9 (9.9) |

34,4 (1.3) |

21,5 (-5.8) |

5.5 (−14.7) |

−4,5 (−20.3) |

−12,7 (−24.8) |

| Record bas ° F (° C) | −29 (-34) |

−25 (−32) |

−11 (-24) |

−2 (−19) |

19 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

42 (6) |

40 (4) |

17 (−8) |

−2 (−19) |

−18 (−28) |

−25 (−32) |

−29 (-34) |

| Précipitations moyennes en pouces (mm) | 0,41 (dix) |

0,37 (9.4) |

0,92 (23) |

1,71 (43) |

2.12 (54) |

1,98 (50) |

2,16 (55) |

1,69 (43) |

0,96 (24) |

1,02 (26) |

0,61 (15) |

0,35 (8.9) |

14h30 (363) |

| Hauteur moyenne de neige en pouces (cm) | 7,0 (18) |

5.7 (14) |

10.7 (27) |

6.8 (17) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.3 (3.3) |

4.0 (dix) |

8.7 (22) |

8.5 (22) |

53,8 (137) |

| Nombre moyen de précipitations (≥ 0,01 po) | 4.1 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 6,5 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 79,7 |

| Jours de neige moyens (≥ 0,1 po) | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 33,3 |

| Humidité relative moyenne (%) | 55.2 | 55,8 | 53,7 | 49,6 | 51,7 | 49,3 | 47,8 | 49,3 | 50,1 | 49,2 | 56,3 | 56,6 | 52,0 |

| Ensoleillement mensuel moyen | 215,3 | 211.1 | 255,6 | 276,2 | 290.0 | 315.3 | 325.0 | 306.4 | 272.3 | 249,2 | 194,3 | 195,9 | 3 106,6 |

| Pourcentage de soleil possible | 72 | 70 | 69 | 69 | 65 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 65 | 67 | 70 |

| Source: NOAA (dim 1961−1990)[64][73][74][75] | |||||||||||||

| Données climatiques pour Denver | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mois | Jan | fév | Mar | avr | Mai | Juin | juil | Août | SEP | oct | nov | déc | Année |

| Heures de lumière du jour moyennes | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9,0 | 12.2 |

| Indice ultraviolet moyen | 2 | 3 | 5 | sept | 9 | dix | 11 | dix | sept | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6.2 |

| Source: Atlas météorologique[76] | |||||||||||||

La démographie[[modifier]

| Population historique | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recensement | Pop. | % ± | |

| 1860 | 4 749 | – | |

| 1870 | 4 759 | 0,2% | |

| 1880 | 35 629 | 648,7% | |

| 1890 | 106 713 | 199,5% | |

| 1900 | 133 859 | 25,4% | |

| 1910 | 213 381 | 59,4% | |

| 1920 | 256 491 | 20,2% | |

| 1930 | 287,861 | 12,2% | |

| 1940 | 322 412 | 12,0% | |

| 1950 | 415 765 | 29,0% | |

| 1960 | 493 887 | 18,8% | |

| 1970 | 514 678 | 4,2% | |

| 1980 | 492,686 | −4,3% | |

| 1990 | 467 610 | −5,1% | |

| 2000 | 554,636 | 18,6% | |

| 2010 | 600 158 | 8,2% | |

| Est. 2018 | 716 492 | [15] | 19,4% |

| Recensement décennal américain[77] | |||

Au recensement de 2010, la ville et le comté de Denver comptaient 600 158 habitants, ce qui en fait la 24e ville la plus peuplée des États-Unis.[80] La région métropolitaine de statistiques de Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO, avait une population estimée à 2 697 476 habitants en 2013 et se classait au 21ème rang des régions métropolitaines statistiques les plus peuplées des États-Unis.[19] et la plus grande zone statistique combinée de Denver-Aurora-Boulder comptait en 2013 une population estimée à 3 277 309 habitants et se classait au 16e rang des régions métropolitaines des États-Unis les plus peuplées.[19] Denver est la ville la plus peuplée dans un rayon de 890 km (890 km).[19] Denverites est un terme utilisé pour les résidents de Denver.

Selon le recensement de 2010, la ville et le comté de Denver comptaient 600 158 personnes et 285 797 ménages. La densité de population était de 3 698 habitants par mile carré (1 428 / km²), y compris l'aéroport. Il y avait 285 797 unités de logement à une densité moyenne de 1,751 par mile carré (676 / km ²).[18] Cependant, la densité moyenne dans la plupart des quartiers de Denver a tendance à être plus élevée. Sans le code postal 80249 (47,3 km carrés, 8 407 résidents) près de l'aéroport, la densité moyenne augmente à environ 5 470 par mile carré.[81] Denver, au Colorado, figure en tête de la liste des meilleurs endroits où vivre en 2017, selon Nouvelles américaines et rapport mondial, se classant parmi les deux premiers en termes d’abordabilité et de qualité de vie.[82]

Selon le recensement des États-Unis de 2010, la composition raciale de Denver était la suivante:

Environ 70,3% de la population (plus de cinq ans) ne parlait que l'anglais à la maison. 23,5% de la population parlait espagnol à la maison. En termes d'ascendance, 31,2% étaient d'origine mexicaine, 14,6% de la population était d'origine allemande, 9,7% d'ascendance irlandaise, 8,9% d'ascendance anglaise et 4,0% d'ascendance italienne.

Il y avait 250 906 ménages, dont 23,2% avaient des enfants de moins de 18 ans vivant avec eux, 34,7% étaient des couples mariés vivant ensemble, 10,8% avaient une femme au foyer sans mari présent et 50,1% étaient des personnes hors famille. 39,3% des ménages étaient composés d'individus et 9,4% avaient une personne seule âgée de 65 ans ou plus. La taille moyenne des ménages était de 2,27 et la taille moyenne de la famille était de 3,14.

La répartition par âge était de 22,0% chez les moins de 18 ans, 10,7% de 18 à 24 ans, 36,1% de 25 à 44 ans, 20,0% de 45 à 64 ans et 11,3% de personnes âgées de 65 ans et plus. L'âge médian est de 33 ans. Au total, il y avait 102,1 hommes pour 100 femmes. En raison d’un sex-ratio asymétrique où les hommes célibataires sont plus nombreux que les femmes célibataires, certains protologues ont surnommé la ville Menver.[83]

Le revenu médian des ménages était de 45 438 $ et le revenu médian de la famille était de 48 195 $. Les hommes avaient un revenu médian de 36 232 $ contre 33 768 $ pour les femmes. Le revenu par tête pour la ville était 24.101 $. 19,1% de la population et 14,6% des familles étaient en dessous du seuil de pauvreté. Sur la population totale, 25,3% des moins de 18 ans et 13,7% des 65 ans et plus vivaient en dessous du seuil de pauvreté.[84]

Les langues[[modifier]

À partir de 2010[update], 72,28% (386 815) des habitants de Denver âgés de 5 ans et plus ne parlaient que l'anglais à la maison, tandis que 21,42% (114 635) parlaient espagnol, 0,85% (4 550) vietnamien, 0,57% (3 073) langues africaines, 0,53% (2 845) russe, 0,50% (2 681) chinois, 0,47% (2 527) français et 0,46% (2 465) allemand. Au total, 27,72% (148 335) des cinq ans et plus de Denver parlaient une langue autre que l'anglais.[85]

Longévité[[modifier]

Selon un article paru dans le journal de l'American Medical Association, les habitants de Denver avaient une espérance de vie de 2014 de 80,02 ans.[86]

Économie[[modifier]

Le produit métropolitain brut de la MSA de Denver s'élevait à 157,6 milliards de dollars en 2010, ce qui en fait la 18e économie métropolitaine en importance aux États-Unis.[88] L’économie de Denver repose en partie sur sa position géographique et son lien avec certains des principaux systèmes de transport du pays. Parce que Denver est la plus grande ville à moins de 800 km (800 km), elle est devenue un lieu naturel de stockage et de distribution de biens et de services vers les États de la Montagne, les États du Sud-Ouest et tous les États de l’Ouest. Un autre avantage pour la distribution est que Denver est presque à égale distance des grandes villes du Midwest, telles que Chicago et Saint-Louis, et de certaines grandes villes de la côte ouest, telles que Los Angeles et San Francisco.

Au fil des ans, la ville a accueilli d’autres grandes entreprises du centre des États-Unis, faisant de Denver un centre commercial clé pour le pays. Plusieurs entreprises bien connues sont originaires ou ont déménagé à Denver. William Ainsworth a ouvert la Denver Instrument Company en 1895 pour créer des balances analytiques destinées aux doseurs d’or. Son usine est maintenant à Arvada. AIMCO (NYSE: AIV) – le plus grand propriétaire et exploitant de communautés d'appartements aux États-Unis, avec environ 870 communautés représentant près de 136 000 unités dans 44 États – a son siège à Denver et emploie environ 3 500 personnes. Samsonite Corp., le plus grand fabricant mondial de bagages, a commencé à Denver en 1910 sous le nom de Shwayder Trunk Manufacturing Company, mais Samsonite a fermé son usine de NE Denver en 2001 et a transféré son siège social dans le Massachusetts après un changement de propriétaire en 2006. The Mountain States Telephone & Telegraph Company, fondée à Denver en 1911, fait maintenant partie du géant des télécommunications CenturyLink.

Le 31 octobre 1937, Continental Airlines, maintenant United Airlines, a transféré son siège à l'aéroport Stapleton de Denver, au Colorado. Robert F. Six a décidé de faire déménager son siège à Denver depuis El Paso, au Texas, parce que Six estimait que la compagnie aérienne devrait avoir son siège dans une grande ville avec une base potentielle de clients.

MediaNews Group a acheté le Denver Post en 1987; la société est basée à Denver. La société Gates Corporation, le plus grand producteur mondial de courroies et de tuyaux automobiles, a été créée à S. Denver en 1919. Russell Stover Candies a fabriqué son premier bonbon au chocolat à Denver en 1923, mais a déménagé à Kansas City en 1969. La Wright & McGill Company a been making its Eagle Claw brand of fishing gear in NE Denver since 1925. The original Frontier Airlines began operations at Denver's old Stapleton International Airport in 1950; Frontier was reincarnated at DIA in 1994. Scott's Liquid Gold, Inc., has been making furniture polish in Denver since 1954. Village Inn restaurants began as a single pancake house in Denver in 1958. Big O Tires, LLC, of Centennial opened its first franchise in 1962 in Denver. The Shane Company sold its first diamond jewelry in 1971 in Denver. In 1973 Re/Max made Denver its headquarters. Johns Manville Corp., a manufacturer of insulation and roofing products, relocated its headquarters to Denver from New York in 1972. CH2M HILL Inc., an engineering and construction firm, relocated from Oregon to the Denver Technological Center in 1980. The Ball Corporation sold its glass business in Indiana in the 1990s and moved to suburban Broomfield; Ball has several operations in greater Denver.

Molson Coors Brewing Company established its U.S. headquarters in Denver in 2005. Its subsidiary and regional wholesale distributor, Coors Distributing Company, is in NW Denver. The Newmont Mining Corporation, the second-largest gold producer in North America and one of the largest in the world, is headquartered in Denver. MapQuest, an online site for maps, directions and business listings, is headquartered in Denver's LoDo district.

Large Denver-area employers that have headquarters elsewhere include Lockheed Martin Corp., United Airlines, Kroger Co. and Xcel Energy, Inc.

Geography also allows Denver to have a considerable government presence, with many federal agencies based or having offices in the Denver area. Along with federal agencies come many companies based on US defense and space projects, and more jobs are brought to the city by virtue of its being the capital of the state of Colorado. The Denver area is home to the former nuclear weapons plant Rocky Flats, the Denver Federal Center, Byron G. Rogers Federal Building and United States Courthouse, the Denver Mint, and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

In 2005, a $310.7 million expansion for the Colorado Convention Center was completed, doubling its size. The hope was the center's expansion would elevate the city to one of the top 10 cities in the nation for holding a convention.[89]

Denver's position near the mineral-rich Rocky Mountains encouraged mining and energy companies to spring up in the area. In the early days of the city, gold and silver booms and busts played a large role in the city's economic success. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the energy crisis in America and resulting high oil prices created an energy boom in Denver captured in the soap opera Dynasty. Denver was built up considerably during this time with the construction of many new downtown skyscrapers. When the price of oil dropped from $34 a barrel in 1981 to $9 a barrel in 1986, the Denver economy also dropped, leaving almost 15,000 oil industry workers in the area unemployed (including former mayor and governor John Hickenlooper, a former geologist), and the nation's highest office vacancy rate (30%).[90] The industry has recovered and the region has 700 employed petroleum engineers.[91] Advances in hydraulic fracturing have made the DJ Basin of Colorado into an accessible and lucrative oil play. Energy and mining are still important in Denver's economy today, with companies such as EnCana, Halliburton, Smith International, Rio Tinto Group, Newmont Mining, and Noble Energy, headquartered or having significant operations. Denver is in 149th place in terms of the cost of doing business in the United States.[92]

Denver's west-central geographic location in the Mountain Time Zone (UTC−7) also benefits the telecommunications industry by allowing communication with both North American coasts, South America, Europe, and Asia in the same business day. Denver's location on the 105th meridian at over one mile (1.6 km) in elevation also enables it to be the largest city in the U.S. to offer a "one-bounce" real-time satellite uplink to six continents in the same business day. Qwest Communications now part of CenturyLink, Dish Network Corporation, Starz, DIRECTV, and Comcast are a few of the many telecommunications companies with operations in the Denver area. These and other high-tech companies had a boom in Denver in the mid to late 1990s. After a rise in unemployment in the Great Recession, Denver's unemployment rate recovered and had one of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation at 2.6% in November 2016.[93] As of December 2016, the unemployment rate for the Denver-Aurora-Broomfield MSA is 2.6%.[94] The Downtown region has seen increased real estate investment[95] with the construction of several new skyscrapers from 2010 onward and major development around Denver Union Station.

Denver has also enjoyed success as a pioneer in the fast-casual restaurant industry, with many popular national chain restaurants founded and based in Denver. Chipotle Mexican Grill, Quiznos, and Smashburger were founded and headquartered in Denver. Qdoba Mexican Grill, Noodles & Company, and Good Times Burgers & Frozen Custard originated in Denver, but have moved their headquarters to the suburbs of Wheat Ridge, Broomfield, and Golden, respectively.

In 2015, Denver ranked No. 1 on Forbes' list of the Best Places for Business and Careers.[96]

Culture and contemporary life[[modifier]

Apollo Hall opened soon after the city's founding in 1859 and staged many plays for eager settlers.[27] In the 1880s Horace Tabor built Denver's first opera house. After the start of the 20th century, city leaders embarked on a city beautification program that created many of the city's parks, parkways, museums, and the Municipal Auditorium, which was home to the 1908 Democratic National Convention and is now known as the Ellie Caulkins Opera House. Denver and the metropolitan areas around it continued to support culture. In 1988, voters in the Denver Metropolitan Area approved the Scientific and Cultural Facilities Tax (commonly known as SCFD), a 0.1% (1 cent per $10) sales tax that contributes money to various cultural and scientific facilities and organizations throughout the Metro area.[97] The tax was renewed by voters in 1994 and 2004 and allows the SCFD to operate until 2018.[98]

Denver is home to a wide array of museums.[99] Denver has many nationally recognized museums, including a new wing for the Denver Art Museum by world-renowned architect Daniel Libeskind, the second largest Performing Arts Center in the nation after Lincoln Center in New York City and bustling neighborhoods such as LoDo, filled with art galleries, restaurants, bars and clubs. That is part of the reason why Denver was, in 2006, recognized for the third year in a row as the best city for singles.[100] Denver's neighborhoods also continue their influx of diverse people and businesses while the city's cultural institutions grow and prosper. The city acquired the estate of abstract expressionist painter Clyfford Still in 2004 and built a museum to exhibit his works near the Denver Art Museum.[101]

The Denver Museum of Nature and Science holds an aquamarine specimen valued at over $1 million, as well as specimens of the state mineral, rhodochrosite. Every September the Denver Mart, at 451 E. 58th Avenue, hosts a gem and mineral show.[102] The state history museum, History Colorado Center, opened in April 2012. It features hands-on and interactive exhibits, artifacts and programs about Colorado history.[103] It was named in 2013 by True West Magazine as one of the top-ten "must see" history museums in the country.[104] History Colorado's Byers-Evans House Museum and the Molly Brown House are nearby.

Denver has numerous art districts around the city, including Denver's Art District on Santa Fe and the River North Art District (RiNo).[105]

While Denver may not be as recognized for historical musical prominence as some other American cities, it has an active pop, jazz, jam, folk, metal, and classical music scene, which has nurtured several artists and genres to regional, national, and even international attention. Of particular note is Denver's importance in the folk scene of the 1960s and 1970s. Well-known folk artists such as Bob Dylan, Judy Collins and John Denver lived in Denver at various points during this time and performed at local clubs.[106] Three members of the widely popular group Earth, Wind, and Fire are also from Denver. More recent Denver-based artists include Nathaniel Rateliff & the Night Sweats, The Lumineers, Air Dubai, The Fray, Flobots, Cephalic Carnage, Axe Murder Boyz, Deuce Mob, Havok, Bloodstrike, Primitive Man, and Five Iron Frenzy.

Because of its proximity to the mountains and generally sunny weather, Denver has gained a reputation as being a very active, outdoor-oriented city. Many Denver residents spend the weekends in the mountains; skiing in the winter and hiking, climbing, kayaking, and camping in the summer.

Denver and surrounding cities are home to a large number of local and national breweries. Many of the region's restaurants have on-site breweries, and some larger brewers offer tours, including Coors and New Belgium Brewing Company. The city also welcomes visitors from around the world when it hosts the annual Great American Beer Festival each fall.

Denver used to be a major trading center for beef and livestock when ranchers would drive (or later transport) cattle to the Denver Union Stockyards for sale. As a celebration of that history, for more than a century Denver has hosted the annual National Western Stock Show, attracting as many as 10,000 animals and 700,000 attendees. The show is held every January at the National Western Complex northeast of downtown.

Denver has one of the country's largest populations of Mexican Americans and hosts four large Mexican American celebrations: Cinco de Mayo (with over 500,000 attendees),[107] in May; El Grito de la Independencia, in September; the annual Lowrider show, and the Dia De Los Muertos art shows/events in North Denver's Highland neighborhood, and the Lincoln Park neighborhood in the original section of West Denver.

Denver is also famous for its dedication to New Mexican cuisine and the chile. It's best known for its green and red chile sauce, Colorado burrito, Southwest (Denver) omelette, breakfast burrito, chiles rellenos, and tamales. Denver is also well known for other types of food such as Rocky Mountain oysters, rainbow trout, and the Denver sandwich.

The Dragon Boat Festival in July, Moon Festival in September and Chinese New Year are annual events in Denver for the Chinese and Asian-American communities. Chinese hot pot (huo guo) and Korean BBQ restaurants have been growing in popularity. The Denver area has 2 Chinese newspapers, the Chinese American Post et le Colorado Chinese News.[108]

Denver has long been a place tolerant of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) community. Many gay bars can be found on Colfax Avenue and on South Broadway. Every June, Denver hosts the annual Denver PrideFest in Civic Center Park, the largest LGBTQ Pride festival in the Rocky Mountain region.[109]

Denver is the setting for The Bill Engvall Show, Tim Allen's Last Man Standing and the 18th season of MTV's The Real World. It was also the setting for the prime time drama Dynasty from 1981 to 1989 (although the show was mostly filmed in Los Angeles). From 1998 to 2002 the city's Alameda East Veterinary Hospital was home to the Animal Planet series Emergency Vets, which spun off three documentary specials and the current Animal Planet series E-Vet Interns. The city is also the setting for the Disney Channel sitcom Good Luck Charlie.

Denver is home to a variety of sports teams and is one of 13 U.S. cities with teams from four major sports (the Denver metro area is the smallest metropolitan area to have a team in all four major sports). Including MLS soccer, it is one of 10 cities to have five major sports teams. The Denver Broncos of the National Football League have drawn crowds of over 70,000 since their origins in the early 1960s, and continue to draw fans today to their current home Empower Field at Mile High. The Broncos have sold out every home game (except for strike-replacement games) since 1970.[110] The Broncos have advanced to eight Super Bowls and won back-to-back titles in 1997 and 1998, and won again in 2015.

The Colorado Rockies were created as an expansion franchise in 1993 and Coors Field opened in 1995. The Rockies advanced to the playoffs that year, but were eliminated in the first round. In 2007, they advanced to the playoffs as a wild-card entrant, won the NL Championship Series, and brought the World Series to Denver for the first time but were swept in four games by the Boston Red Sox.

Denver has been home to two National Hockey League teams. The Colorado Rockies played from 1976 to 1982, but became the New Jersey Devils. The Colorado Avalanche joined in 1995, after relocating from Quebec City. While in Denver, they have won two Stanley Cups in 1996 and in 2001. The Denver Nuggets joined the American Basketball Association in 1967 and the National Basketball Association in 1976. The Avalanche and Nuggets have played at Pepsi Center since 1999. The Major League Soccer team Colorado Rapids play in Dick's Sporting Goods Park, an 18,000-seat soccer-specific stadium opened for the 2007 MLS season in the Denver suburb of Commerce City.[111] The Rapids won the MLS Cup in 2010.

Denver has several additional professional teams. In 2006 Denver established a Major League Lacrosse team, the Denver Outlaws. They play in Empower Field at Mile High. In 2006, the Denver Outlaws won the Western Conference Championship, and then went on to become 2014 MLL Champions, eight years later. The Colorado Mammoth of the National Lacrosse League play at the Pepsi Center.

In 2018 the Denver Bandits were established as the first professional football team for women in Colorado, and will be a part of the initial season for the Women's National Football Conference WNFC in 2019.

Denver submitted the winning bid to host the 1976 Winter Olympics but subsequently withdrew, giving it the dubious distinction of being the only city to back out after having won its bid to host the Olympics.[46] Denver and Colorado Springs hosted the 1962 World Ice Hockey Championships.

Parks and recreation[[modifier]

As of 2006[update], Denver had over 200 parks, from small mini-parks all over the city to the giant 314-acre (1.27 km2) City Park.[117] Denver also has 29 recreation centers providing places and programming for resident's recreation and relaxation.[118]

Many of Denver's parks were acquired from state lands in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This coincided with the City Beautiful movement, and Denver mayor Robert Speer (1904–12 and 1916–18) set out to expand and beautify the city's parks. Reinhard Schuetze was the city's first landscape architect, and he brought his German-educated landscaping genius to Washington Park, Cheesman Park, and City Park among others. Speer used Schuetze as well as other landscape architects such as Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and Saco Rienk DeBoer to design not only parks such as Civic Center Park, but many city parkways and tree-lawns. All of this greenery was fed with South Platte River water diverted through the city ditch.[119]

In addition to the parks within Denver, the city acquired land for mountain parks starting in the 1911s.[120] Over the years, Denver has acquired, built and maintained approximately 14,000 acres (57 km2) of mountain parks, including Red Rocks Park, which is known for its scenery and musical history revolving around the unique Red Rocks Amphitheatre.[121][122] Denver also owns the mountain on which the Winter Park Resort ski area operates in Grand County, 67 miles (110 km) west of Denver.[123] City parks are important places for Denverites and visitors, inciting controversy with every change. Denver continues to grow its park system with the development of many new parks along the Platte River through the city, and with Central Park and Bluff Lake Nature Center in the Stapleton neighborhood redevelopment. All of these parks are important gathering places for residents and allow what was once a dry plain to be lush, active, and green. Denver is also home to a large network of public community gardens, most of which are managed by Denver Urban Gardens, a non-profit organization.

Since 1974, Denver and the surrounding jurisdictions have rehabilitated the urban South Platte River and its tributaries for recreational use by hikers and cyclists. The main stem of the South Platte River Greenway runs along the South Platte from Chatfield Reservoir 35 miles (56 km) into Adams County in the north. The Greenway project is recognized as one of the best urban reclamation projects in the U.S., winning, for example, the Silver Medal Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence in 2001.[124]

In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land, a national land conservation organization, reported Denver had the 17th best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[125]

Government[[modifier]

Denver is a consolidated city-county with a mayor elected on a nonpartisan ballot, a 13-member city council and an auditor. The Denver City Council is elected from 11 districts with two at-large council-members and is responsible for passing and changing all laws, resolutions, and ordinances, usually after a public hearing, and can also call for misconduct investigations of Denver's departmental officials. All elected officials have four-year terms, with a maximum of three terms. The current mayor is Michael Hancock.

Denver has a strong mayor/weak city council government. The mayor can approve or veto any ordinances or resolutions approved by the council, makes sure all contracts with the city are kept and performed, signs all bonds and contracts, is responsible for the city budget, and can appoint people to various city departments, organizations, and commissions. However, the council can override the mayor's veto with a nine out of thirteen member vote, and the city budget must be approved and can be changed by a simple majority vote of the council. The auditor checks all expenditures and may refuse to allow specific ones, usually based on financial reasons.[126]

The Denver Department of Safety oversees three branches: the Denver Police Department, Denver Fire Department, and Denver Sheriff Department. The Denver County Court is an integrated Colorado County Court and Municipal Court and is managed by Denver instead of the state.

Politics[[modifier]

While Denver elections are non-partisan, Democrats have long dominated the city's politics; most citywide officials are known to be Democrats. The mayor's office has been occupied by a Democrat since the 1963 municipal election. All of the city's seats in the state legislature are held by Democrats.

In federal elections, Denverites also tend to vote for Democratic candidates, voting for the Democratic Presidential nominee in every election since 1960, excluding 1972 and 1980. At the federal level, Denver is the heart of Colorado's 1st congressional district, which includes all of Denver and parts of Arapahoe County. It is represented by Democrat Diana DeGette.

Benjamin F. Stapleton was the mayor of Denver, Colorado, for two periods, the first from 1923 to 1931 and the second from 1935 to 1947. Stapleton was responsible for many civic improvements, notably during his second stint as mayor when he had access to funds and manpower from the New Deal. During this time, the park system was considerably expanded and the Civic Center completed. His signature project was the construction of Denver Municipal Airport, which began in 1929 amidst heavy criticism. It was later renamed Stapleton International Airport in his honor. Today, the airport has been replaced by a neighborhood also named Stapleton. Stapleton Street continues to bear his name.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Denver was one of the epicenters of the Chicano Movement. The boxer-turned-activist Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales formed an organization called the Crusade for Justice, which battled police brutality, fought for bilingual education, and, most notably, hosted the First National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in March 1969.[127]

In recent years, Denver has taken a stance on helping people who are or become homeless, particularly under the administrations of mayors John Hickenlooper and Wellington Webb. At a rate of 19 homeless per 10,000 residents in 2011 as compared to 50 or more per 10,000 residents for the four metro areas with the highest rate of homelessness,[128] Denver's homeless population and rate of homeless are both considerably lower than many other major cities. However, residents of the city streets suffer Denver winters – which, although mild and dry much of the time, can have brief periods of extremely cold temperatures and snow.

In 2005, Denver became the first major city in the U.S. to vote to make the private possession of less than an ounce of marijuana legal for adults 21 and older.[129] The city voted 53.5 percent in favor of the marijuana legalization measure, which, as then-mayor John Hickenlooper pointed out, was without effect, because the city cannot usurp state law, which at that time treated marijuana possession in much the same way as a speeding ticket, with fines of up to $100 and no jail time.[129] Denver passed an initiative in the fourth quarter of 2007 requiring the mayor to appoint an 11-member review panel to monitor the city's compliance with the 2005 ordinance.[130] In 2012, Colorado Amendment 64 was signed into law by Governor John Hickenlooper and at the beginning of 2014 Colorado became the first state to allow the sale of marijuana for recreational use.[131]

In May 2019, Denver became the first U.S. city to decriminalize psilocybin mushrooms after an initiative passed with 50.6% of the vote. The measure prohibits Denver from using any resources to prosecute adults over 21 for personal use of psilocybin mushrooms, though such use remains illegal under state and federal law.[132][133]

Former Denver mayor John Hickenlooper was a member of the Mayors Against Illegal Guns Coalition,[134] an organization formed in 2006 and co-chaired by New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg and Boston mayor Thomas Menino.

Denver hosted the 2008 Democratic National Convention, which was the centennial of the city's first hosting of the landmark 1908 convention. It also hosted the G7 (now G8) summit between June 20 and 22 in 1997 and the 2000 National Convention of the Green Party.[135][136] In 1972, 1981, and 2008, Denver also played host to the Libertarian Party of the United States National Convention. The 1972 Convention was notable for nominating Tonie Nathan as the Vice Presidential candidate, the first woman, as well as the first Jew, to receive an electoral vote in a United States presidential election.

On October 31, 2011, it was announced The University of Denver in Denver would host the first of three 2012 presidential debates to be held on October 3, 2012.[[citation requise]

In July 2019, Mayor Hancock said that Denver will not assist U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents with immigration raids.[137]

Presidential election results

| Année | Républicain | Democratic | Autres |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 18.9% 62,690 | 73.7% 244,551 | 7.4% 24,611 |

| 2012 | 24.2% 73,111 | 73.4% 222,018 | 2.4% 7,289 |

| 2008 | 23.0% 62,567 | 75.5% 204,882 | 1.5% 4,084 |

| 2004 | 29.3% 69,903 | 69.6% 166,135 | 1.2% 2,788 |

| 2000 | 30.9% 61,224 | 61,9% 122,693 | 7.3% 14,430 |

| 1996 | 30.0% 58,529 | 61.8% 120,312 | 8.2% 15,973 |

| 1992 | 25.4% 55,418 | 56.0% 121,961 | 18.6% 40,540 |

| 1988 | 37.1% 77,753 | 60.7% 127,173 | 2.2% 4,504 |

| 1984 | 47.8% 105,096 | 50.2% 110,200 | 2.0% 4,442 |

| 1980 | 42.2% 88,398 | 41.0% 85,903 | 16.8% 35,207 |

| 1976 | 46.7% 105,960 | 49.5% 112,229 | 3.8% 8,549 |

| 1972 | 54.1% 121,995 | 43.5% 98,062 | 2.3% 5,278 |

| 1968 | 43.5% 92,003 | 50.2% 106,081 | 6.3% 13,233 |

| 1964 | 33.6% 73,279 | 65.7% 143,480 | 0,7% 1,529 |

| 1960 | 49.6% 109,446 | 49.7% 109,637 | 0,7% 1,618 |

| 1956 | 55.9% 121,402 | 43.2% 93,812 | 0,9% 1,907 |

| 1952 | 56.1% 119,792 | 43.2% 92,237 | 0,7% 1,534 |

| 1948 | 45.2% 76,364 | 52.9% 89,489 | 1.9% 3,214 |

| 1944 | 48.8% 86,331 | 50.8% 90,001 | 0.4% 759 |

| 1940 | 46.9% 81,328 | 52.5% 90,938 | 0.6% 1,105 |

| 1936 | 33.3% 50,743 | 65.1% 99,263 | 1.6% 2,486 |

| 1932 | 43.5% 59,372 | 53.4% 72,868 | 3.2% 4,318 |

| 1928 | 63.4% 73,543 | 35.6% 41,238 | 1.1% 1,221 |

| 1924 | 63.4% 59,077 | 16.9% 15,764 | 19.6% 18,282 |

| 1920 | 62.0% 43,581 | 32.5% 22,839 | 5.5% 3,838 |

| 1916 | 33.8% 23,185 | 62.8% 43,029 | 3.4% 2,298 |

| 1912 | 13.6% 8,155 | 44.5% 26,690 | 41.9% 25,171 |

Taxes[[modifier]

The City and County of Denver levies an Occupational Privilege Tax (OPT or head tax) on employers and employees.

- If any employee performs work in the city limits and is paid over $500 for that work in a single month, the employee and employer are both liable for the OPT regardless of where the main business office is located or headquartered.

- The employer is liable for $4 per employee per month and the employee is liable for $5.75 per month.

- It is the employer's responsibility to withhold, remit, and file the OPT returns. If an employer does not comply, the employer can be held liable for both portions of the OPT as well as penalties and interest.

Éducation[[modifier]

Denver Public Schools (DPS) is the public school system in Denver. It educates approximately 92,000 students in 92 elementary schools, 18 K-8 schools, 34 middle schools, 44 high schools, and 19 charter schools.[139] The first school of what is now DPS was a log cabin that opened in 1859 on the corner of 12th Street between Market and Larimer Streets. The district boundaries are coextensive with the city limits.[140] The Cherry Creek School District serves some areas with Denver postal addresses that are outside the city limits.[140][141]

Denver's many colleges and universities range in age and study programs. Three major public schools constitute the Auraria Campus: the University of Colorado Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver, and Community College of Denver. The private University of Denver was the first institution of higher learning in the city and was founded in 1864. Other prominent Denver higher education institutions include Johnson & Wales University, Catholic (Jesuit) Regis University and the city has Roman Catholic and Jewish institutions, as well as a health sciences school. In addition to those schools within the city, there are a number of schools throughout the surrounding metro area.

The Denver Metropolitan Area is served by a variety of media outlets in print, radio, television, and the Internet.

Television stations[[modifier]

Denver is the 16th-largest market in the country for television, according to the 2009–2010 rankings from Nielsen Media Research.

- KWGN-TV, channel 2, is a CW affiliate owned by Tribune Broadcasting. Tribune also owns KDVR, the Fox affiliate on channel 31, and KWGN is controlled by KDVR management. KWGN is Colorado's first television station, signing on the air in July 1952.

- KCNC-TV, channel 4, is a CBS owned and operated station.

- KRMA-TV, channel 6, is the flagship outlet of Rocky Mountain PBS, a statewide network of Public Broadcasting Service stations. Programming on KRMA is rebroadcast to four other stations throughout Colorado.

- KMGH-TV, channel 7, is an ABC affiliate owned by the E.W. Scripps Company, previously owned by the McGraw-Hill company from 1972 to January 2012.

- KUSA-TV, channel 9, is an NBC affiliate, owned by Tegna, Inc.. TEGNA also owns KTVD, the MyNetworkTV affiliate on channel 20.

- KBDI-TV, channel 12, is Denver's secondary PBS affiliate.

- KDEN-TV, channel 25, is a Telemundo-owned station.

- KDVR, channel 31, is Denver's FOX affiliate.

- KPJR-TV, channel 38, is a Trinity Broadcasting Network-owned station.

- KCEC, channel 50, is the Univision affiliate.

- KETD, channel 53, is a Christian station owned by the LeSEA Broadcasting group.

Radio stations[[modifier]

Denver is also served by over 40 AM and FM radio stations, covering a wide variety of formats and styles. Denver-Boulder radio is the No. 19 market in the United States, according to the Spring 2011 Arbitron ranking (up from No. 20 in Fall 2009).

For a list of radio stations, see Radio Stations in Colorado.

Impression[[modifier]

After a continued rivalry between Denver's two main newspapers, the Denver Post et Rocky Mountain News, the papers merged operations in 2001 under a Joint Operating Agreement that formed the Denver Newspaper Agency[142] until February 2009 when E. W. Scripps Company, the owner of the Rocky Mountain News, closed the paper. There are also several alternative or localized newspapers published in Denver, including the Westword, Law Week Colorado, Out Front Colorado et le Intermountain Jewish News. Denver is home to multiple regional magazines such as 5280, which takes its name from the city's mile-high elevation (5,280 feet or 1,609 meters).

Transport[[modifier]

City streets[[modifier]

Most of Denver has a straightforward street grid oriented to the four cardinal directions. Blocks are usually identified in hundreds from the median streets, identified as "00", which are Broadway (the east–west median, running north–south) and Ellsworth Avenue (the north–south median, running east–west). Colfax Avenue, a major east–west artery through Denver, is 15 blocks (1500) north of the median. Avenues north of Ellsworth are numbered (with the exception of Colfax Avenue and several others, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd and Montview Blvd.), while avenues south of Ellsworth are named.

There is also an older downtown grid system that was designed to be parallel to the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. Most of the streets downtown and in LoDo run northeast–southwest and northwest–southeast. This system has an unplanned benefit for snow removal; if the streets were in a normal N–S/E–W grid, only the N–S streets would receive sunlight. With the grid oriented to the diagonal directions, the NW–SE streets receive sunlight to melt snow in the morning and the NE–SW streets receive it in the afternoon. This idea was from Henry Brown the founder of the Brown Palace Hotel. There is now a plaque across the street from the Brown Palace Hotel that honors this idea. The NW–SE streets are numbered, while the NE–SW streets are named. The named streets start at the intersection of Colfax Avenue and Broadway with the block-long Cheyenne Place. The numbered streets start underneath the Colfax and I-25 viaducts. There are 27 named and 44 numbered streets on this grid. There are also a few vestiges of the old grid system in the normal grid, such as Park Avenue, Morrison Road, and Speer Boulevard. Larimer Street, named after William Larimer, Jr., the founder of Denver, which is in the heart of LoDo, is the oldest street in Denver.

All roads in the downtown grid system are streets (e.g. 16th Street, Stout Street). Roads outside that system that travel east/west are given the suffix "avenue" and those that head north and south are given the "street" suffix (e.g. Colfax Avenue, Lincoln Street). Boulevards are higher capacity streets and travel any direction (more commonly north and south). Smaller roads are sometimes referred to as places, drives (though not all drives are smaller capacity roads, some are major thoroughfares) or courts. Most streets outside the area between Broadway and Colorado Boulevard are organized alphabetically from the city's center.

Some Denver streets have bicycle lanes, leaving a patchwork of disjointed routes throughout the city. There are over 850 miles[143] of paved, off-road, bike paths in Denver parks and along bodies of water, like Cherry Creek and the South Platte. This allows for a significant portion of Denver's population to be bicycle commuters and has led to Denver being known as a bicycle-friendly city.[144] Some residents are very opposed to bike lanes, which have caused some plans to be watered down or nixed. The review process for one bike line on Broadway will last over a year before city council members will make a decision. In addition to the many bike paths, Denver launched B-Cycle – a citywide bicycle sharing program – in late April 2010. The B-Cycle network was the largest in the United States at the time of its launch, boasting 400 bicycles.[145]

The Denver Boot, a car-disabling device, was first used in Denver.[146]

Cyclisme[[modifier]

The League of American Bicyclists has rated Colorado as the sixth most bicycle-friendly state in the nation for the year 2014. This is due in large part to Front Range cities like Boulder, Fort Collins and Denver placing an emphasis on legislation, programs and infrastructure developments that promote cycling as a mode of transportation.[147] Walk score has rated Denver as the fourth most bicycle-friendly large city in the United States.[148]

According to data from the 2011 American Community Survey, Denver ranks 6th among US cities with populations over 400,000 in terms of the percentage of workers who commute by bicycle at 2.2% of commuters.[149] B-Cycle – Denver's citywide bicycle sharing program – was the largest in the United States at the time of its launch, boasting 400 bicycles.[145] Through the acquisition of new grants, the program has expanded each year, adding dozens of new stations and hundreds of bikes, and beginning service during the winter months.[150][151]

Micro-mobility[[modifier]

In 2018, Denver entered the public micro-mobility[152] space with dockless electric scooters and e-bike services. Hundreds of unsanctioned LimeBike and Bird electric scooters appeared on Denver streets in May, causing an uproar. The scooters were nixed in June;[153] the city scrambled to create an official city pilot program, making a requirement that scooters be left at RTD stops and out of the public right-of-way. Lime and Bird scooters then reappeared in late July, with limited compliance. Uber's Jump e-bikes arrived in late August, followed by Lyft's nationwide electric scooter launch in early September.[154] Lyft plans to offer ride-sharing, electric scooter and e-bike services all from its app. It says that it will, each night, take the scooters to the warehouse for safety checks, maintenance and charging. Additionally, Spin and Razor each were permitted to add 350 scooters to the mix.[155]

Walkability[[modifier]

2017 rankings by Walk Score placed Denver twenty-sixth among 108 U.S. cities with a population of 200,000 or greater.[148] City leaders have acknowledged the concerns of walkability advocates that Denver has serious gaps in its sidewalk network. The 2019 Denver Moves: Pedestrians plan outlines a need for approximate $1.3 billion in sidewalk funding, plus $400 million for trails.[156] Denver does not currently have resources to fully fund this plan.[157]

Modal characteristics[[modifier]

In 2015, 9.6 percent of Denver households lacked a car, and in 2016, this was virtually unchanged (9.4 percent). The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Denver averaged 1.62 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[158]

Freeways and highways[[modifier]

Denver is primarily served by the interstate freeways I-25 and I-70. The problematic intersection of the two interstates is referred to locally as "the mousetrap" because, when viewed from the air, the junction (and subsequent vehicles) resemble mice in a large trap.

Interstate 25 runs north–south from New Mexico through Denver to Wyoming

Interstate 25 runs north–south from New Mexico through Denver to Wyoming Interstate 225 traverses neighboring Aurora. I-225 was designed to link Aurora with I-25 in the southeastern corner of Denver, and I-70 to the north of Aurora, with construction starting May 1964 and ending May 21, 1976.

Interstate 225 traverses neighboring Aurora. I-225 was designed to link Aurora with I-25 in the southeastern corner of Denver, and I-70 to the north of Aurora, with construction starting May 1964 and ending May 21, 1976. Interstate 70 runs east–west from Utah to Maryland. It is also the primary corridor on which Denverites access the mountains. A proposed $1.2 billion widening of an urban portion through a primarily low-income and Latino community has been met with community protests and calls to reroute the interstate along the less urban Interstate 270 alignment. They cite increased pollution and the negative effects of tripling the interstates large footprint through the neighborhood as primary objections. The affected neighborhood bisected by the Interstate was also designated the most polluted neighborhood in the country and is home to a Superfund site.[159]

Interstate 70 runs east–west from Utah to Maryland. It is also the primary corridor on which Denverites access the mountains. A proposed $1.2 billion widening of an urban portion through a primarily low-income and Latino community has been met with community protests and calls to reroute the interstate along the less urban Interstate 270 alignment. They cite increased pollution and the negative effects of tripling the interstates large footprint through the neighborhood as primary objections. The affected neighborhood bisected by the Interstate was also designated the most polluted neighborhood in the country and is home to a Superfund site.[159] Interstate 270 runs concurrently with US 36 from an interchange with Interstate 70 in northeast Denver to an interchange with Interstate 25 north of Denver. The freeway continues as US 36 from the interchange with Interstate 25.

Interstate 270 runs concurrently with US 36 from an interchange with Interstate 70 in northeast Denver to an interchange with Interstate 25 north of Denver. The freeway continues as US 36 from the interchange with Interstate 25. Interstate 76 begins from I-70 just west of the city in Arvada. It intersects I-25 north of the city and runs northeast to Nebraska where it ends at I-80.

Interstate 76 begins from I-70 just west of the city in Arvada. It intersects I-25 north of the city and runs northeast to Nebraska where it ends at I-80. US 6 follows the alignment of 6th Avenue west of I-25, and connects downtown Denver to the west-central suburbs of Golden and Lakewood. It continues west through Utah and Nevada to Bishop, California. To the east, it continues as far as Provincetown, on Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

US 6 follows the alignment of 6th Avenue west of I-25, and connects downtown Denver to the west-central suburbs of Golden and Lakewood. It continues west through Utah and Nevada to Bishop, California. To the east, it continues as far as Provincetown, on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. US 285 ends its 847 Mile route through New Mexico and Texas at Interstate 25 in the University Hills Neighborhood.

US 285 ends its 847 Mile route through New Mexico and Texas at Interstate 25 in the University Hills Neighborhood. US 85 also travels through Denver. This Highway is often used as an alternate route to Castle Rock instead of taking Interstate 25.

US 85 also travels through Denver. This Highway is often used as an alternate route to Castle Rock instead of taking Interstate 25. US 36 connects Denver to Boulder and Rocky Mountain National Park near Estes Park. It runs east into Ohio, after crossing four other states.

US 36 connects Denver to Boulder and Rocky Mountain National Park near Estes Park. It runs east into Ohio, after crossing four other states. State Highway 93 starts in the Western Metropolitan area in Golden, Colorado and travels almost 19 miles to meet with SH 119 in central Boulder. This highway is often used as an alternate route to Boulder instead of taking US 36.

State Highway 93 starts in the Western Metropolitan area in Golden, Colorado and travels almost 19 miles to meet with SH 119 in central Boulder. This highway is often used as an alternate route to Boulder instead of taking US 36. State Highway 470 (C-470, SH 470) is the southwestern portion of the Denver metro area's beltway. Originally planned as Interstate 470 in the 1960s, the beltway project was attacked on environmental impact grounds and the interstate beltway was never built. The portion of "Interstate 470" built as a state highway is the present-day SH 470, which is a freeway for its entire length.

State Highway 470 (C-470, SH 470) is the southwestern portion of the Denver metro area's beltway. Originally planned as Interstate 470 in the 1960s, the beltway project was attacked on environmental impact grounds and the interstate beltway was never built. The portion of "Interstate 470" built as a state highway is the present-day SH 470, which is a freeway for its entire length.

Denver also has a nearly complete beltway known as "the 470's". These are SH 470 (also known as C-470), a freeway in the southwest Metro area, and two toll highways, E-470 (from southeast to northeast) and Northwest Parkway (from terminus of E-470 to US 36). SH 470 was intended to be I-470 and built with federal highway funds, but the funding was redirected to complete conversion of downtown Denver's 16th Street to a pedestrian mall. As a result, construction was delayed until 1980 after state and local legislation was passed.[160] I-470 was also once called "The Silver Stake Highway", from Gov. Lamm's declared intention to drive a silver stake through it and kill it.

A highway expansion and transit project for the southern I-25 corridor, dubbed T-REX (Transportation Expansion Project), was completed on November 17, 2006.[161] The project installed wider and additional highway lanes, and improved highway access and drainage. The project also includes a light rail line that traverses from downtown to the south end of the metro area at Lincoln Avenue.[162] The project spanned almost 19 miles (31 km) along the highway with an additional line traveling parallel to part of I-225, stopping just short of Parker Road.

Metro Denver highway conditions can be accessed on the Colorado Department of Transportation website Traffic Conditions.[163]

Mass transportation[[modifier]

Mass transportation throughout the Denver metropolitan area is managed and coordinated by the Regional Transportation District (RTD). RTD operates more than 1,000 buses serving over 10,000 bus stops in 38 municipal jurisdictions in eight counties around the Denver and Boulder metropolitan areas. Additionally, RTD operates nine rail lines, the A, B, C, D, E, F, G, L, R, W, and H with a total of 57.9 miles (93.2 km) of track, serving 44 stations. The C, D, E, F, L, R, W and H lines are light rail while the A Line, B Line and G Line are commuter rail.

FasTracks is a commuter rail, light rail, and bus expansion project approved by voters in 2004, which will serve neighboring suburbs and communities. The W Line, or West line, opened in April 2013 serving Golden/Federal Center. The commuter rail A Line from Denver Union Station to Denver International Airport opened in April 2016 with ridership exceeding RTD's early expectations.[164] The light rail R Line through Aurora opened in February 2017.[165] Two additional commuter rail lines are planned to open in the near future with the G Line to the suburb of Arvada opening on April 26, 2019 after being originally planned to open in the Fall of 2016,[166] and the N Line to Commerce City and Thornton, currently estimated to be open in Spring 2020.[167]